Now then, the very fact that these striking provisions were not invoked by Israel and the United States in their coordinated attacks on Iran, establishes the practical limitations of the international law mechanism as a material basis for de-escalation.

The globalists’ school include the International Court of Justice, the principal organ judicial organ of the UN, resolving inter-state disputes through judicial means and providing advisory opinions on international law. Others of this philosophical bent include the International Centre for the Settlement of investment Disputes (ICSID); which provides a forum for the resolution of international investment disputes impacting sovereigns and foreign investors.

Notwithstanding the benign allure of the globalists’ school of thought, it has been often been criticised as sedate, supine, and unresponsive to the immediate and remote complexities and significant challenges confronting nations on issues ranging from national security, geoeconomic threats, illegal migration, ethno-terrorism, narco-terrorism, drug trafficking, people smuggling, techno-nationalism et al.

Accordingly, there is scarcely any meeting of minds between the hawks and the globalists on fundamental issues of policy and sharp divergence on ideological viewpoints. The inescapable outcome therefore, is tension with some nation states adopting ideologically hawkish positions whilst others adopt the globalists’ standpoint.

Can there be consensus on that basis? And this is not just on account of ideological differences, but on germane issues like security, domestic and foreign policy, where overriding national interests define sovereigns’ strategic policy aspirations and choices. Clearly, geopolitical, national interests and security considerations scale the grand aspirations of the international law at critical moments.

Yet, irrespective of whether an independent nation adopts a hawkish or globalist philosophical stance, certain international treaties constrain the exercise of sovereign autonomy in its truest sense. For emphasis, sovereign autonomy implies independence and self-governance of a state or entity, where it exercises the supreme, independent, power to make decisions and act without external influence or control; plus, the capacity to regulate its own affairs, make laws and enforce them.

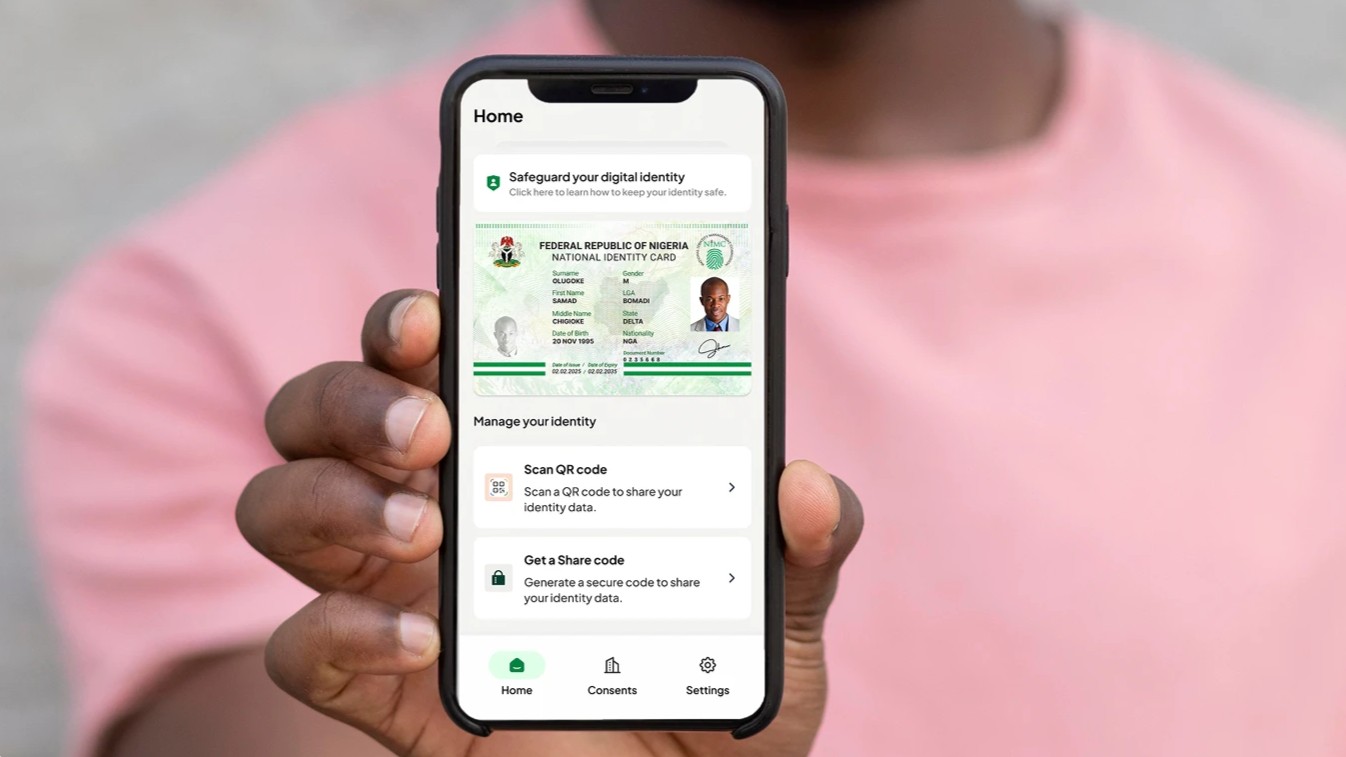

Statutory force for this assertion is established, inter alia, by the provisions of sections 1 (1), (2), and (3) of Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution (as amended) viz: This Constitution is supreme and its provisions shall have binding force on the authorities and persons throughout the Federal Republic of Nigeria; The Federal Republic of Nigeria shall not be governed, nor shall any persons or group of persons take control of the Government of Nigeria or any part thereof, except in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution; and, if any other law is inconsistent with the provisions of the Constitution, the Constitution shall prevail, and that other law shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.

However, the far-reaching capacity of a range of multi-lateral institutions to influence domestic policy exemplifies real constraints on sovereign autonomy. On one spectrum are organisations like the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organisation, and the World Bank which impact domestic policy through “oversight” functions, flexible or punitive loan conditions, onerous technical assistance terms.

On the other, are organisations like the International Atomic Energy Agency (op.cit), which is in direct issue here, as its 12 June 2025 report formed the de facto policy basis for the Israeli and U.S. attacks on Iranian nuclear and military targets.

The IAEA “NPT Safeguards Agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran Resolution, GOV/25/38 adopted on June 12, 2025, established amongst other things established; “the Director General’s conclusion contained in GOV/2025/25 that Iran did not declare nuclear material and nuclear-related activities at three undeclared locations in Iran, specifically, Lavisan-Shian, Varamin, and Turquzabad, and that, because of the lack of technically credible answers by Iran, the Agency is not in a position to determine whether the nuclear material at these undeclared locations in Iran has been consumed, mixed with other declared material, or is still outside of Safeguards”; and “Noting with concern the Director General’s conclusion, most recently in GOV/2025/25, that these issues stem from Iran’s obligations under its NPT Safeguards Agreement and unless and until Iran assists the Agency is resolving the outstanding issues, the Agency will not be in a position to provide assurance that Iran’s nuclear programme is exclusively peaceful…”

In other words, Iran’s sovereign autonomy was constrained by its accession to the NPT, which, of necessity, granted the IAEA, the capacity to exercise investigative powers and recommendations for international sanctions, over what should ordinarily be a matter of Iran’s domestic jurisdiction; nuclear power. Thus, wittingly or unwittingly, the IAEA is caught up in the geopolitical crosshairs of the U.S./Israeli attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities and the wider crisis in the Persian Gulf.

Nevertheless, no country is compelled to execute the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which seeks to impede the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to foster the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and to further the goal of disarmament. The Treaty establishes a safeguards system under the responsibility of the IAEA, which also plays a central role under the Treaty in areas of technology transfer for peaceful purposes. For perspective, the NPT became effective on 5 March 1970.

Iran, which at the time, was led by the Western and pro-Israeli ally, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, ratified the NPT in 1970 committing to: not developing or acquiring nuclear weapons; allowing IAEA inspections and monitoring to verify compliance; and utilising nuclear technology strictly for peaceful purposes. Notably, Israel, India, Pakistan, and South Sudan, have not ratified the NPT given overriding strategic considerations.

Thus far, Iran has not withdrawn from the NPT. Accordingly, at international law, the country, like 179 others, remains bound by the treaty provisions given its membership of the UN’s IAEA and ratification of these international agreements. Notwithstanding the geopolitics of the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979 which toppled Pahlavi, and ushered in Ayatollah Khomeini and a succession of theocratic supreme leaders, Iran as a sovereign entity, remains a legal, physical, and jurisprudential continuum, bound by treaty obligations.

North Korea, for example, acceded to the NPT in 1985, but which exercised its sovereign autonomy by serving the requisite notice and withdrawing from the treaty in 2003 on the grounds of strategic interests. What stopped Iran from exiting the NPT? In not too dissimilar circumstances, citing strategic nation interests, the United States exited the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty on 14 June, 2002.

The U.S. invoked Article 15 of the treaty, which allowed either party to withdraw with six months’ notice if it decided that extraordinary events related to the subject matter of the treaty had jeopardised its supreme interests to activate its withdrawal.

In the final analysis, there is a compelling and urgent rationale for deescalating the ongoing war between the United States-Israel versus Iran, not least because it risks extensive global insecurity, far-reaching wars, and the progressive instability around the world by those for and against the conflict.

Equally, there could be a harmonisation of positions between hawks and globalists if the UN Charter is reviewed to enhance its operational effectiveness, reach, and impact, by making it nimble and more fit for purpose. Plus, rules certainly matter and no nation is compelled to ratify treaties in dynamic and volatile global order.

For Nigeria, the case for a nuanced foreign policy is robust given current and emerging geopolitical threats, national security, and strategic risks. The country is a signatory to the United Nations 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). For treaty parties like Nigeria, it prohibits the development, testing, production, stockpiling, stationing, transfer, use and threat of use of nuclear weapons, as well as assistance and encouragement to the prohibited activities.

In addition, for nuclear armed states joining the treaty, it provides for a time bound framework for negotiations leading to the verified and irreversible elimination of its nuclear weapons programme. In other words, given the horrific spectre of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, the treaty seeks to eradicate nuclear weapons.

Be that as it may, Nigeria should exercise a strategic deterrence capability, which implies the need to review treaties and international legal entanglements which may not advance the country’s national interests over the short, medium and longer term. It is political naivete to assume that other countries, however powerful, will put Nigeria’s strategic interests before their own. No! It doesn’t work that way as can be gleaned from the foregoing.

National interests will always come first and if the strategic defence logic justifies a nuclear deterrence by India, Israel, Pakistan and the permanent five UNSC (United States, Russia, China, United Kingdom, and France) members, why not Nigeria? Surely, this will not happen overnight nevertheless, now is the time for serious strategic thinking and action.

Concluded.

Ojumu is the Principal Partner at Balliol Myers LP, a firm of legal practitioners and strategy consultants in Lagos, Nigeria, author of The Dynamic Intersections of Economics, Foreign Relations, Jurisprudence and National Development (2023).