At Balogun Market on Lagos Island, a market woman once told me: “Petrol price rises like the afternoon sun. It does not matter who will get burned, it will happen fast and bad.”

Her words stuck with me. Nigeria’s downstream petroleum sector is “officially” deregulated. This process was supposed to liberate prices, invite competition and break the grip of monopolies.

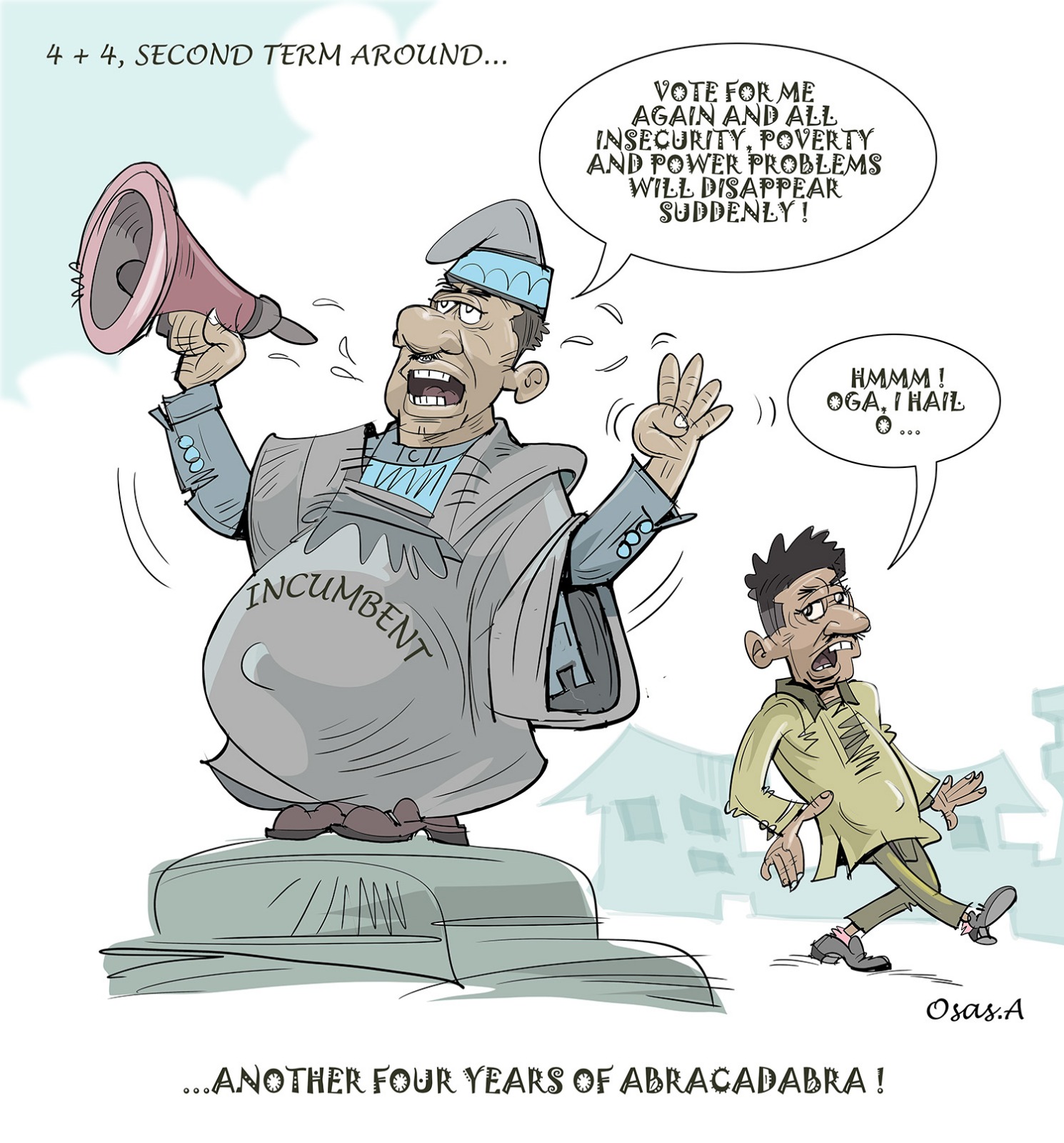

Yet here we are: pump prices swing wildly, small distributors vanish overnight, and we see the growth of a giant dominating every link in the chain. Deregulation is now a pantomime of some sort; a performance of free markets, where the script seems tightly held by a privileged few.

This promise is seductive. The government removed price controls and subsidies so that Nigeria would attract investment, spur innovation and align its energy sector with global efficiencies in a bid to “let the market decide.” But markets don’t exist in a vacuum. They are shaped in the image of the people who hold power within them, and in Nigeria, power seems to always pool in the same hands, decade after decade.

But without sounding cynical, there has been progress. Nigeria’s Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) has been a genuine leap forward, and it coincided with the national triumph of the arrival of the Dangote Refinery, capable of refining 650,000 barrels of petrol a day. But, this is the rub: When one private refinery can dominate a market of 200 million people, it is difficult to think, have we traded a public monopoly for a private one? This also is not about vilifying success; I’m just asking why Nigeria, with 200 million ambitious and talented people, only just a few reach the starting line.

Is this open competition or just a mirage of deregulation?

Obviously, deregulation has not failed. It has just been outmanoeuvred. The Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (FCCPC), which is tasked with ensuring fair play in the Nigerian markets, seems to be hamstrung by technicalities or, maybe, something even less benign.

Let’s look at the licensing for new petroleum marketers. On paper, the process is simple: demonstrate financial capacity and wait for approval. But in practice, some delays get stretched, applications seemingly get “lost”, and fees mysteriously balloon up.

I spoke with an aspiring importer last month, and he explained: “It feels like someone keeps stretching the length of the tunnel and switching off the light at the end.”

But extremely wealthy players can operate with ease. Even now, we are seeing players in the supply chain find their places in the market threatened through uncompetitive price fixing. Still, the government and regulators have a lukewarm attitude to enforcing any true policies to make the market fairer. Even for the average Nigerian, filling up their generator or car tank is a gamble.

The art of regulatory capture

A truly competitive market requires much more than removing price controls. There needs to be vigilant guardianship against anti-competitive behaviour. But it seems like the FCCPC’s enforcement is uneven, reactive, and selective. Every accusation of wrongdoing in the market seems to come with the blank promise to “monitor the situation.” But we are seeing the FCCPC morph from a regulatory agency to an income-generating agency through fines.

This asymmetry doesn’t seem accidental. This is how it is done in textbooks. It raises the question of whether Nigeria’s watchdogs are too cosy with the same giants they are supposed to oversee.

To regular Nigerians, the market seems “free” only in name. In structure, it resembles old feudalism. The Nigerian dream of smaller businesses springing up within the petroleum industry seems impossible. New entrants feel “this industry is not for us.”

The human cost of phantom competition

The ugly consequences of this exist outside city centres in Nigeria. Independent petrol stations that were once symbols of entrepreneurship and a growing Nigeria now dot the landscape like relics. Those that remain look scant and are surviving on razor-thin margins. The old majors are now the order of the day as independents are unable to match the bulk purchasing power of the majors.

Independent marketers are unable to survive due to the state of today’s market, where prices fluctuate, and some players have been accused of anti-competitive pricing that also threatens their business entirely.

“We are forced to buy what we don’t want,” one owner in the Igando area of Lagos told me. “Their price is not what my former marketer is saying is the market price. What choice do we now have?”

Consumers are feeling the pinch too. One day, the price is down, the next day, it is up and very high too. Households are unable to make plans based on the prices of petrol.

When a handful or one major player controls supply, the prices will become less about the market dynamics and more about internal calculus. Suddenly, a pipeline hiccup, or currency fluctuation or even a refinery maintenance shutdown will become the perfect pretext for a price hike. And when alternatives are few or do not even exist within the market, Nigerians will be forced to either pay up, queue for hours, or return to the dark times of the Nigerian black market, where quality and safety are a gamble.

What is a good intention?

The government is not inherently or universally the villain. Classical and neoclassical-trained economists and political scientists believe deregulation is the path to prosperity: “leave the market and allow it to fix itself.” But, we can’t “good intention” our way out of systemic flaws.

Take our push for modular refineries. Of course, on paper, it is a win for competition and a route to decentralised production. But, where is the support and infrastructure to encourage players to get into the market? We have barely seen any progress on that front. Over time, it can be expected that even if independent modular players come into the market, they will end up swallowed by the larger entities within a few years.

Also, there is a disturbing dissonance in policy. While it is a fact that the government has dismantled subsidies, it is struggling to dismantle the structures that have made the subsidies necessary in the first place. Why? I can’t tell you, but my guess? Those structures benefit the politically connected. Another guess? Basic economic incompetence. And Nigerians will not be better for the good intentions. Instead, we will find ourselves in a self-perpetuating cycle: monopolies thrive in unstable markets, instability will justify state interventions, and then, that intervention will entrench the monopoly.

What is the path forward?

First, we, as Nigerians, must admit the truth: blanket deregulation alone is not enough. Markets need rules and ruthless enforcement of those rules. The FCCPC must stop being a passive observer. Instead, it must become the assertive referee its act mandates it to be. It must be unafraid to penalise anti-competitive practices regardless of the player’s size. This requires political will, adequate funding and a cultural shift in the commission itself.

Second, sunlight is the best disinfectant. The licensing criteria, petroleum data, and pricing should be published, and approval processes streamlined, with a public dashboard tracking applications, delays, and providing reasons for rejection. Other regulatory agencies should also build out public dashboards to ensure the entire market is transparent.

Third, alternatives must be empowered. Tax benefits for new entrants, grants and new protocols like cooperative models should be encouraged, as well as state governments getting into the refinery game. To create more competition for the good of everybody in Nigeria.

The stakes of reform that isn’t reform

Nigeria’s dream of equitable opportunity is hinging on getting this right. We need to go beyond the economic viewpoints of a fair market and see it for what it truly should be: a social contract. When we, the people, see that wealth remains recycled by the same players, our faith in institutions gets eroded. We are witnessing the growth of cynicism. We don’t want deregulation to become another broken promise in a long line of promises of the Nigerian government to Nigerians.

Nigerian entrepreneurs with brilliant ideas are scared of Nigeria because everybody keeps saying “The market is open,” but who is it open for?

Until Nigeria confronts this question honestly, the illusion of deregulation will be just that.

Adeniji is an economic analyst based in Lagos