I have just finished reading a book “What Britain Did To Nigeria” by Max Siollun, who is an authority on issues that affects Nigeria. Mr Siollun has written several books on Nigeria including “Soldiers of Fortune, Nigeria Politics from Buhari to Babangida and Nigeria’s soldiers of fortune—The Abacha and Obasanjo Years. Expectedly his latest book, “What Britain did to Nigeria” is very educative and informative; the 390-page book is published by C.Hurst & Co.(Publishers) Ltd. One of the articles in the book caught my serious attention, the title which is the mistake of 1914.

The article summarises what one should know about Nigeria on the amalgamation that took place in 1914. Mr Siollun declared “Perhaps no question makes Nigerians disagree as much as why Britain created their country. Nigerians looking for deeper meaning for their country’s existence may be disappointed to find that there was none. Nigeria’s existence is little more than the outcome of balancing the colonial accounting books. In 1900 Britain created two countries with similar-sounding names. These were the protectorates of Northern Nigeria and Southern Nigeria.

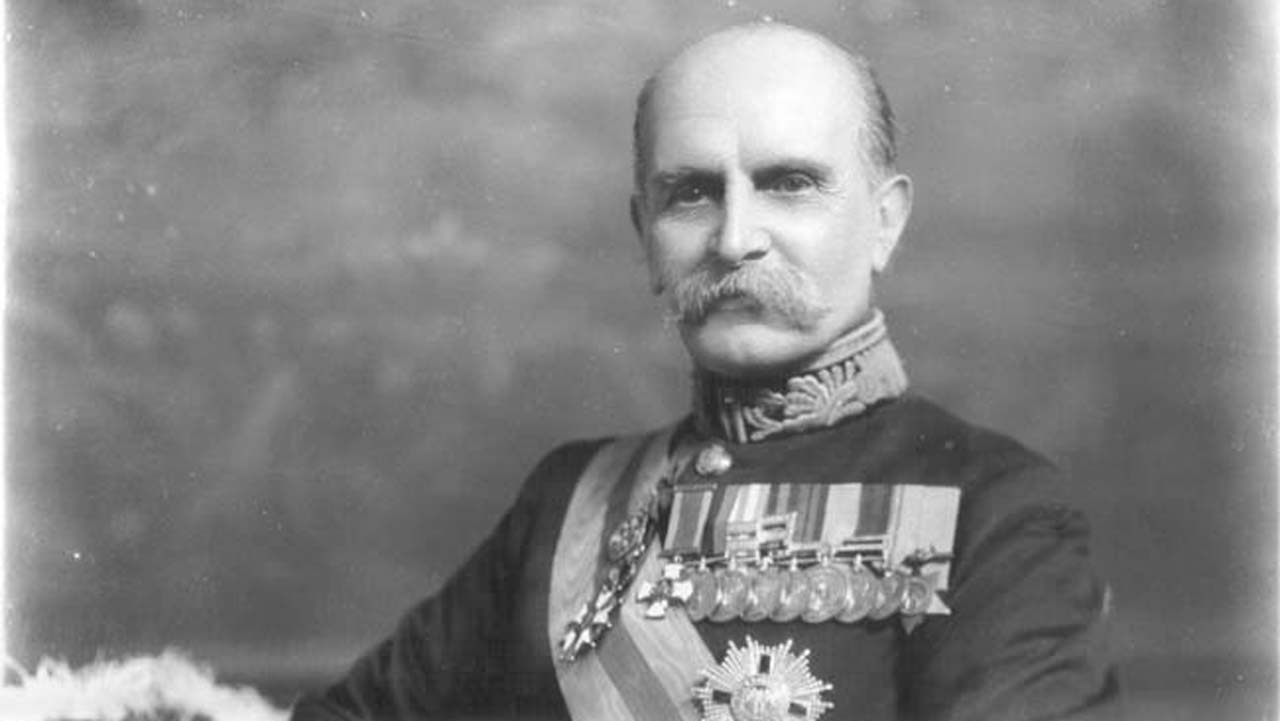

For 14 years these two countries were separately governed by different high commissioners. Lugard was Britain’s first high commissioner for Northern Nigeria and Sir Ralph Moor was his counterpart in Southern Nigeria. The two colonies had different colonial personnel, legal systems, land tenure laws, educational policies and systems of governance.

Their eventual amalgamation on 1 January 1914 was not sudden. It was the culmination of a process that, as we have seen, began 16 years earlier with the recommendation of the Niger Committee. Although Lugard is credited as being the architect of Nigeria’s amalgamation, the process started long before he became Northern Nigeria’s high commissioner or the governor-general of the combined Nigeria in 1914.

‘These jolly laughing trading black men’

Some British accounts of the differences between the people in the two Nigerians mentioned (with the usual poor a anthropological insight of that era) that ‘the inhabit Northern Nigeria are very different from the coast Negroes [Southern Nigeria]’ and flippantly described northerners as ‘black-faced Mohammedan Arabs with an admixture of negro strain’ and southerners as ‘these jolly laughing trading black men’. Although this is a very simplistic summary, others offered a more realistic assessment. Sir George Goldie, who advocated the amalgamation of Southern Nigeria and Northern Nigeria, admitted that the two countries were ‘as widely separated government, customs, and general ideas about life, both world and the next, as England is from China’. Since Britain was aware of the sharp differences between the two Nigerias, why did it decide to amalgamate them anyway?

Just as British entry into Nigeria was motivated by economic reasons, so was its amalgamation into one country. The duplication of finances and personnel in running two separate colonies in the same area was an impediment to administrative efficiency. The need for British colonies to be self-financing made amalgamation a priority. Since Northern Nigeria had no coastline and was landlocked, it did not receive customs duties, as Southern Nigeria did.

This disadvantage was exacerbated because Northern Nigeria imported goods from Southern Nigeria duty-free, and its costs for transporting its goods to Southern Nigeria for export were also high. Since Southern Nigeria received customs duties and Northern Nigeria did not, a small percentage of customs revenue from the former was sent to the latter. Yet this was not enough to offset Britain’s cost of administering Northern Nigeria. Northern Nigeria had been running on a budget deficit for ten years, during which time its revenue was not enough to meet even half its cost of administration. As a result the British Treasury paid grants-in-aid to Northern Nigeria (totalling over £4 million) in the 14 years of its existence. These were non- refundable payments rather than loans, and were in addition to the £865,000 that the Treasury paid to the Royal Niger Company as compensation for the revocation of its charter.

Such dependency on the Treasury could not continue. Lugard tried to raise revenue by imposing taxation on Northern Nigeria but it was not enough. As early as 1904 he argued: “Northern Nigeria is as yet largely dependent on a grant in aid … I feel myself that economy can only be effected by the realization of Mr. Chamberlain’s original scheme of amalgamating Northern and Southern Nigeria and Lagos into one single administration. It is only in this way that Northern Nigeria, which is the hinterland of the other two, can be properly developed, and economies introduced into the triple machinery which at present exists. The country, which is all one and indivisible, can thus be developed on identical lines, with a common trend of policy in all essential matters.”

‘The material prosperity had been extraordinary’

Lugard’s advocacy of amalgamation ten years before it actually happened is not surprising. As Northern Nigeria’s high commissioner, he faced the problems of the colony’s dependency on grants from the Treasury and the need to find alternative revenue sources. Amalgamating the two Nigerias into one country would not only solve these problems for him, but carried with it a potential promotion, in that he would become the governor of the newly amalgamated country. For Lugard, the solution to his problems lay in Southern Nigeria. He observed: “Southern Nigeria, on the other hand, presented a picture which was in almost all points the exact converse of that in the north. Here the material prosperity had been extraordinary. The revenue had almost doubled itself in a period of five years. The surplus balance exceeded a million and a half. The trade of the interior had greatly developed by the construction of a splendid system of roads, and by the opening to navigation of waterways hitherto choked with vegetation … And so while Northern Nigeria was devoting itself building up a system of Native Administration and laboriously raising a revenue by direct taxation, Southern Nigeria had found itself engrossed in material development.

To be continued tomorrow

Teniola, a former director at the Presidency wrote from Lagos.