The Federal Government’s plan to overhaul Nigeria’s technical education curriculum has drawn cautious reactions from education and economic experts, who insist that the initiative’s success will depend on proper implementation rather than policy design.

Minister of Education, Dr. Maruf Tunji Alausa, had last week announced that the curriculum had been revised to reduce overload, strengthen trade competencies, and align with global standards.

He explained that 26 trade areas had been streamlined to reflect Nigeria’s manufacturing, services, and digital economy needs, while preparing young Nigerians for modern industrial demands.

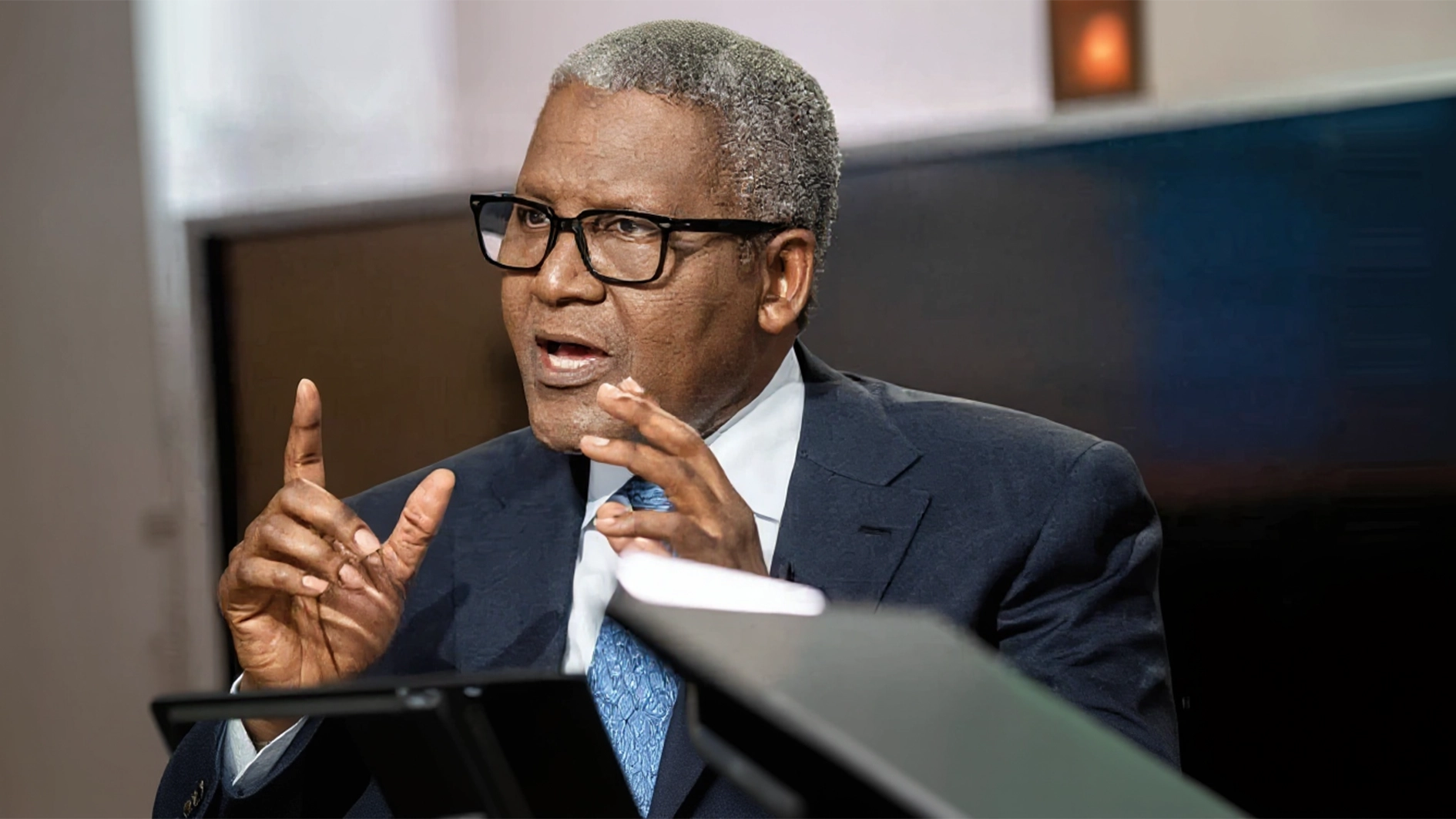

But in an interview, Mr. Bello Audu, Chief Consultant at Economic DTGES and an Innovation Economist at Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, cautioned that the reforms will not yield immediate results without deliberate follow-through.

“The government can do a lot. One is coming up with the policy, the new curriculum—that is the first step in the right direction,” Mr. Audu said. “The next stage now is proper implementation of that policy because policy can be beautiful on paper, but if there’s poor implementation then it will not really achieve the desired aims.”

He noted that schools across the country, both public and private, would need resources and supervision to deliver the new curriculum. “Proper implementation has to be in place and there should be a quality control mechanism to go and check to make sure the new curriculum is being implemented at all levels,” he added.

Mr. Audu further argued that synergy between the three tiers of government is critical. “Whatsoever they have, there should be synergy among the Federal, State, and Local governments so that the policy can be easily implemented, and it has to be implemented without fear or favour for people or schools that fail to implement it,” he said.

The economist also recommended that the Federal Government test the new curriculum in its unity schools and colleges before rolling it out nationwide. “The federal government should have started with federal government schools under its direct supervision. That way, it can review progress, track challenges, and determine manpower needs before wider implementation,” he explained.

He warned that inadequate resources could force schools to cut corners. “The implementation might be poor from the start because many schools might not even have the resources available—the manpower, the structure and the facility. That will be challenging and will bring about schools cutting corners. Ministries at the state level may overlook this because it’s a new policy, so implementation cannot be overnight perfect,” Mr. Audu said.

He also stressed the importance of accountability mechanisms to evaluate outcomes. “They can be able to track students after graduation and consult with them to know how it has impacted their life, what career they pursued, and where improvements are needed,” he said.

While highlighting the challenges, Mr. Audu commended schools already offering vocational training, citing GCC Girls’ Academy in Maiduguri, Borno State, which provides displaced children with practical skills alongside formal education. However, he said the lack of formal backing limits the reach of such initiatives.

“Schools that are already doing those trade and vocational training are commendable. However, not being part of the curriculum makes it lack that formal recognition. Once it is part of the academic calendar, carried out weekly in session, it becomes more impactful,” he said.