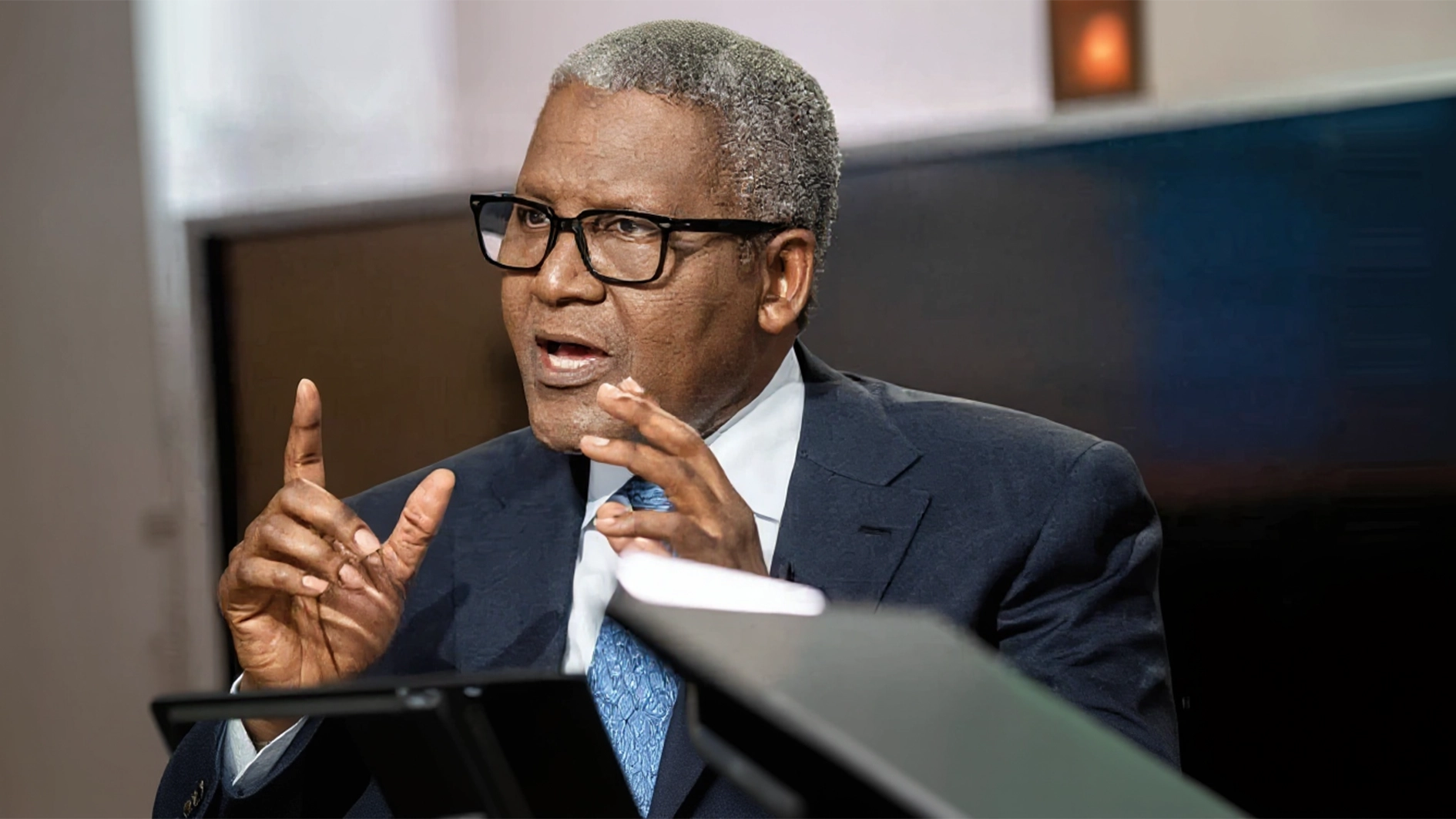

The Minister of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Nyesom Wike, has been in the news lately for slashing the University of Abuja’s (UNIABUJA) land by two-thirds, citing unauthorised acquisition and underutilisation. The decision has generated mixed reactions from stakeholders, including university authorities, alumni, and experts, igniting a debate on land ownership, institutional autonomy, and the role of land in higher education development, particularly in the wake of infrastructural deficits, OWEDE AGBAJILEKE reports.

The recent decision by the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Nyesom Wike, to reduce the University of Abuja’s land allocation from 11,000 hectares to 4,000 hectares is currently generating mixed reactions from all concerned.

The action, which the Minister described as a corrective measure against unauthorised land acquisition and underutilisation, has drawn the ire of stakeholders and ignited a broader debate on the autonomy of universities and higher education development.

At the heart of the dispute is the deeper question about land ownership and the balance between urban development and educational expansion. Land allocation issues have long plagued Nigerian universities. A 2021 report by the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners (NITP) revealed that about one-third of university lands nationwide are prone to encroachment by private developers and government agencies.

For instance, in 2019, Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), Ile-Ife, Osun State, and Great Ife Development Board (GIDB) were at loggerheads over portions of land belonging to the school. Similarly, in March this year, the Edo State Government, through the Task Force on Protection of Government Property, intervened in a series of land encroachment disputes involving the state-owned Ambrose Alli University (AAU), Ekpoma, and the Emaudo community, which allegedly encroached on the school’s vast expanse of land.

Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) is not left out, as it lost over 300 hectares of its land in Samaru due to similar re-allocation in 2022. Speaking at the inauguration of access roads in the Giri District of Abuja, Wike expressed concern over what he described as ‘land grabbing’ by the university, accusing it of fencing off large swathes of land without proper approval or documentation.

The minister ordered the Director of Lands and other relevant FCTA agencies to allocate only 4,000 hectares to the university, while the remaining land will be re-allocated for planned development within the district.

“The university on its own grabbed 11,000 hectares; this is unacceptable. No document; nothing. You see the school fencing everywhere, and before you know it, they would go ahead to sell the land,” Wike fumed.

Established in 1988, UNIABUJA was envisioned as a comprehensive institution that would combine conventional and distance learning models. With over 40,000 students currently enrolled, and a projected population of 60,000 by 2030, many fear that future expansion might be stifled.

Already, the university management has warned that some of its planned faculties and agricultural research zones will be disrupted by the 63.6 per- cent land reduction.

Pundits noted that the decision has also raised questions about the government’s relationship with public universities and land management, with some experts suggesting a land utilisation audit to determine the actual needs of the university.

Findings by The Guardian indicated that Africa’s top-ranked universities, including the University of Cape Town (UCT), are situated on 586 hectares of land; Cairo University, Egypt, occupies 338 hectares, while the University of Johannesburg occupies a land area of 1,032 hectares.

Land sizes of other highly-ranked African tertiary institutions include Stellenbosch University, South Africa (1,790 hectares); American University, Cairo (1,011 hectares); University of Pretoria (1,032 hectares); Makerere University, Uganda (159 hectares); and University of Nairobi (161 hectares), among others.

Supporters of the move described the action as a step in the right direction, as such would help in curbing unauthorised land takeovers, by ensuring public control over FCT lands, supporting urban planning by re-allocating land for infrastructural projects, streamlining land administration and discouraging illegal acquisition.

They argued that the land has been largely underutilised for decades. Public affairs analyst Jonathan Adejor said the debate is not about the quantity of land, but how effectively it is used.

Adejor noted that institutions like the University of Lagos (UNILAG) and Covenant University, Ota, have achieved remarkable academic and research outputs despite having far smaller campuses.

According to him, “It is not the expanse of land that determines a university’s greatness, but the vision, planning, and quality of facilities within it. If the University of Abuja can maximise the 4,000 hectares with modern classrooms, laboratories, hostels, and research centres, it could still become a world-class institution.”

Adejor argued that the government’s move could serve as a wake-up call for public institutions to focus on sustainable land-use strategies that prioritise tangible infrastructure over vast, but underdeveloped spaces.

An alumnus of the institution, Tule Gemanen, also threw his weight behind the minister’s action, arguing that the university had more than enough land to meet its academic and research needs if it adopted a strategic development plan.

He maintained that vast unused portions of the campus had become overgrown, attracting criminal activities and illegal structures, which posed security risks to students and staff.

“The land is too big for the university. With its land mass, the school will not build half of it in 100 years. The truth is that unused land in an urban capital is a wasted asset. Four thousand hectares, if well planned and developed, can serve the university for decades without compromising its growth,” Gemanen said. He further noted that the FCT’s urban expansion required careful balancing between educational needs and the commercial demands of a growing population.

According to him, reallocating surplus land to planned city projects could stimulate economic activity in the area, ultimately benefiting the university and surrounding communities.

Similarly, Dr Toks, a public intellectual and university don, challenged the need for such vast land ownership. In a viral post on X (formerly Twitter), he remarked: “Harvard University across its five campuses sits on approximately 2,000 hectares of land, including its research forests. What is a university doing with 11,000 hectares of land? Which development would occur again after 37 years of existence? It hasn’t used up to 10 per cent of the 11,000 hectares. UNILORIN is sitting on 15,000 hectares of land with less than 10 per cent fully utilised since 1975.”

However, critics described the minister’s approach as unconstitutional, warning of long‑term harm to Nigeria’s educational development. Stakeholders pointed out that Nigerian universities, with extensive land holdings have been able to diversify into ventures such as commercial farming, technology parks, and research villages, initiatives that not only enhance learning, but also generate significant revenue.

They warned that without deliberate safeguards, public institutions could lose critical opportunities for self-sustenance and innovation.Apart from undermining the university’s long-term development prospects, they maintained that underutilisation is not a justification for revocation.

“Land is a long-term investment for future expansion, especially for research, agriculture, and innovation parks,” said Prof. Fatimah Ahmed, a specialist in educational planning at the University of Ibadan. Opposing Wike’s action, the university’s alumni association urged him to rescind his decision and embrace a more constructive and transparent engagement process.

In a letter to the minister, the group expressed deep concern over the move, describing it as “unlawful” and “arbitrary”. Signed by its President, Habeeb Abdulkadir, and General Secretary, Abdullahi Dangana, the group clarified that the land was lawfully allocated to the university in 1988 by the then military government of Ibrahim Babangida.

According to the letter, the master plan for the land includes infrastructure for both conventional and distance learning programmes, as well as designated zones for agricultural, scientific, and environmental research, alongside recreational and community services.

“The proposed revocation of two-thirds of this portion at this time undermines the strategic future of the university, especially as it strives to expand its research capacity, accommodate increasing enrolment, and fulfil its dual-mode mandate,” the association warned.

The alumni insisted that the land is protected under valid legal instruments and the Land Use Act, stressing that any revocation without due process and compensation would violate established land tenure laws and natural justice.

Reacting, the university expressed surprise over the development, insisting that it holds valid title documents for its land, duly issued by relevant authorities, including previous FCT ministers.

The school’s spokesperson, Dr Habib Yakoob, explained that despite encroachments, the university has continued to develop its land, leveraging funding from Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund), the federal government’s appropriations, and internal resources.

Yakoob said: “The announcement has come as a surprise to the university community, because the institution has valid title documents for its land, which were duly issued during its formative years by the appropriate authorities.” He clarified that the documents were granted in line with the university’s present and future development needs.

“Despite encroachments from several fronts, significant developments have been ongoing across the university’s land, supported by TETFund high-impact interventions and funding from the federal government,” Yakoob added. He, however, noted that the school will continue to engage with relevant stakeholders on the need to reason with the only public university in the FCT, which has been very deliberate in the use of its land for purposeful development and long-term growth.

In the coming months, the institution is expected to engage in high-level consultations with the FCT administration to seek a possible review or phased implementation of the land reduction. Alumni associations and civil society groups have already begun lobbying for a compromise that would preserve vital sections of the institution’s master plan.

Whether this yields a middle ground or hardens the standoff will likely depend on how both sides balance the imperatives of urban development with the equally pressing need to future-proof Nigeria’s educational infrastructure.