HIV response in Nigeria has moved beyond the battle against stigmatisation to a fight for the continuity of lifesaving treatment. While the antiretroviral therapy has transformed the disease into a manageable condition, recent disruptions in drug supply, funding uncertainties, and overreliance on external support have exposed the fragility of the national response. IJEOMA NWANOSIKE reports that without strong local investment, sustainable funding, and resilient infrastructure, decades-long progress could be undone, leaving millions at risk of preventable illness, as well as jeopardising what has long been considered a global success.

Nwanma Aladoh (not real name) was 27 when her second child fell ill, and doctors insisted on some laboratory tests. It was in the process that she got the shocking news that her son was HIV-positive. Hours later, her own diagnosis followed, and she was further broken. But what dealt her a blow of seismic proportions was the revelation that her husband, who died months later, knew his HIV status before their marriage, but hid it from his then-fiancée.

“It felt like betrayal from the deepest place,” she said in her unsteady voice while struggling to wipe away tears that were cascading down her cheeks.

Alone with two children and a stigma that she never asked for, Aladoh found that HIV was not the only thing altering her life; people’s reactions were just as devastating. Attempts to rebuild her life were met with quiet rejection as potential partners withdrew the moment they disclosed her status.

“Once you mention HIV, everything changes, the tone, the body language, the willingness to know you,” she summarised.

Even in places meant to offer care, stigmatisation followed her and her children. She recalled nurses treating her son differently during hospital stays, avoiding contact or lowering their voices when discussing his file. “Those small actions leave marks. They remind you that fear and misinformation still sit deeply, even in the health system,” she said.

For many Nigerians living with HIV, stigma was once the heaviest burden. But today, a new fear has emerged, one that threatens the very progress that once saved lives – treatment disruption. One of those who understands that shift succinctly is Grace Omodunbi, who has lived with HIV for 27 years.

For most of her journey, Grace Olatokun was convinced that once she could manage her social life, endure the stigma that often accompanied it, and have accessible treatment, life would hold some predictability. She adhered faithfully to her regimen, found strength in support groups, and carried a quiet pride in her resilience. However, the service disruptions experienced earlier this year, including temporary laboratory closures and drug rationing, deeply unsettled her.

“I thought stigma was the hardest part, but now I know that even after overcoming it, our treatment can be taken from us,” she lamented.

Olatogun’s worry extends beyond temporary shortages. She fears a future where funding cuts or programme withdrawal might force people to buy antiretroviral drugs in open markets – an environment already plagued by counterfeit and substandard medicines.

“If funding cuts or programme withdrawal force patients to buy antiretroviral drugs in open markets, there’s no guarantee that the drugs would be real or safe. Fake Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) can destroy everything we have fought for, and it’s not just the poor who will suffer; money won’t protect anyone, including the rich, if the system collapses,” she said.

Olatogun is not the only one assailed by this fear.

In 1994, long before treatment became widely available in Nigeria, Eghosa Obasohan felt his life slipping away. Rapid weight loss, rashes, and a persistent cough were all symptoms that preceded a diagnosis that, at the time, felt like a death sentence. “It was like being pushed out of the world of the living. The stigma was suffocating, and I was made to feel subhuman,” he recalled.

But what nearly ended Obasohan was not stigma alone; it was the impossibility of accessing treatment. Obasohan told The Guardian that ART costs around N38,000 monthly, a sum far beyond the reach of most Nigerian minimum wage earners. “It created hopelessness like addiction, and people were just waiting to die.”

But what nearly ended Obasohan was not stigma alone; it was the impossibility of accessing treatment. Obasohan told The Guardian that ART costs around N38,000 monthly, a sum far beyond the reach of most Nigerian minimum wage earners. “It created hopelessness like addiction, and people were just waiting to die.”

Relief only came Obasohan’s way when subsidised ART became available near his Ikorodu home – a development he fittingly described as “air returning to his lungs.”

Now, 32 years after his diagnosis, and approaching the anniversary of his infection, which he plans to mark in April 2026, Obasohan rarely thinks about HIV except when he takes his daily medication.

The recent disruptions experienced and the uncertainty around funding are, to say the least, still unsettling.

“Drugs are available now, yes, but for how long? I’m worried about losing the treatment that has kept me safe for three decades. I hope we don’t wake up one day and hear about another disruption,” he told The Guardian.

“Death is inevitable, but everyone deserves a chance to live well while waiting for the inevitable,” he philosophised.

Widening funding gaps and donor fatigue

ADVANCEMENTS in Nigeria’s HIV care, once considered a global success, are facing renewed fragility as funding gaps widen, donor commitments fluctuate, and stigma continues to shape how people seek and receive care.

With recent programme disruptions and rising doubts about future drug availability, the lived experiences of people like Obasohan highlight just how precarious the moment is.

Put differently, without sustained investment and clear ownership of the HIV response, the progress that turned HIV into a manageable condition could push millions back toward fear, instability, and preventable loss.

These fears are amplified by the President of the Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria (NEPWHAN), Mr Abdulkadiri Ibrahim.

In an interview with The Guardian, Ibrahim, who observed that the recent funding cuts initially affected both treatment and prevention activities, noted that even though treatment is currently available, uncertainties persist.

He said: “Even though the treatment is available, the uncertainty is still there because we don’t know, and we are not guaranteed what will happen in the next couple of years. The $200 million approved by the Federal government for HIV, TB, and Malaria is an integrated process, and the government will be the one to determine and provide details on how they will distribute the drug. Sustainability is for the government to invest and continue by taking care of Nigerians.”

Before the national ART programme was introduced in 2002, Nigeria ranked among countries with the highest HIV burdens in the world as the epidemic claimed countless lives and spread with the speed and ferocity of a wildfire.

Sentinel surveys between 1999 and 2001 estimated that three to 3.5 million Nigerians were living with HIV, with national prevalence peaking at 5.8 per cent in 2001, just before widespread treatment began. Although cumulative deaths from those early years were never fully documented, available figures paint a grim picture: roughly 110,000 Nigerians died of AIDS in 2000, and the number had risen to 310,000 by 2003, but since then, the country has made significant strides.

According to the National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA), approximately 1.9 million people are currently living with HIV, with national prevalence now at 1.3 per cent.

In 2024, Nigeria recorded about 74,000 new infections and 42,000 AIDS-related deaths. Yet progress remains uneven. The South-South zone has the highest prevalence at 3.1 per cent, with Akwa Ibom (5.5 per cent) and Benue (5.3 per cent) topping the list among adults aged 15 to 49.

Emerging research suggests the picture may be even more complex. A field study by the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) found a striking 12 per cent HIV prevalence among adolescents and young adults who had never been screened before – nearly 10 times the national average.

Presented by Dr Agatha David and her team, the study screened 883 young people aged 15 to 24 who had never tested for HIV and discovered 106 positive cases. Researchers warned that this age group lags in testing, treatment initiation, and viral suppression, making them a weak link in the national effort to achieve global HIV targets.

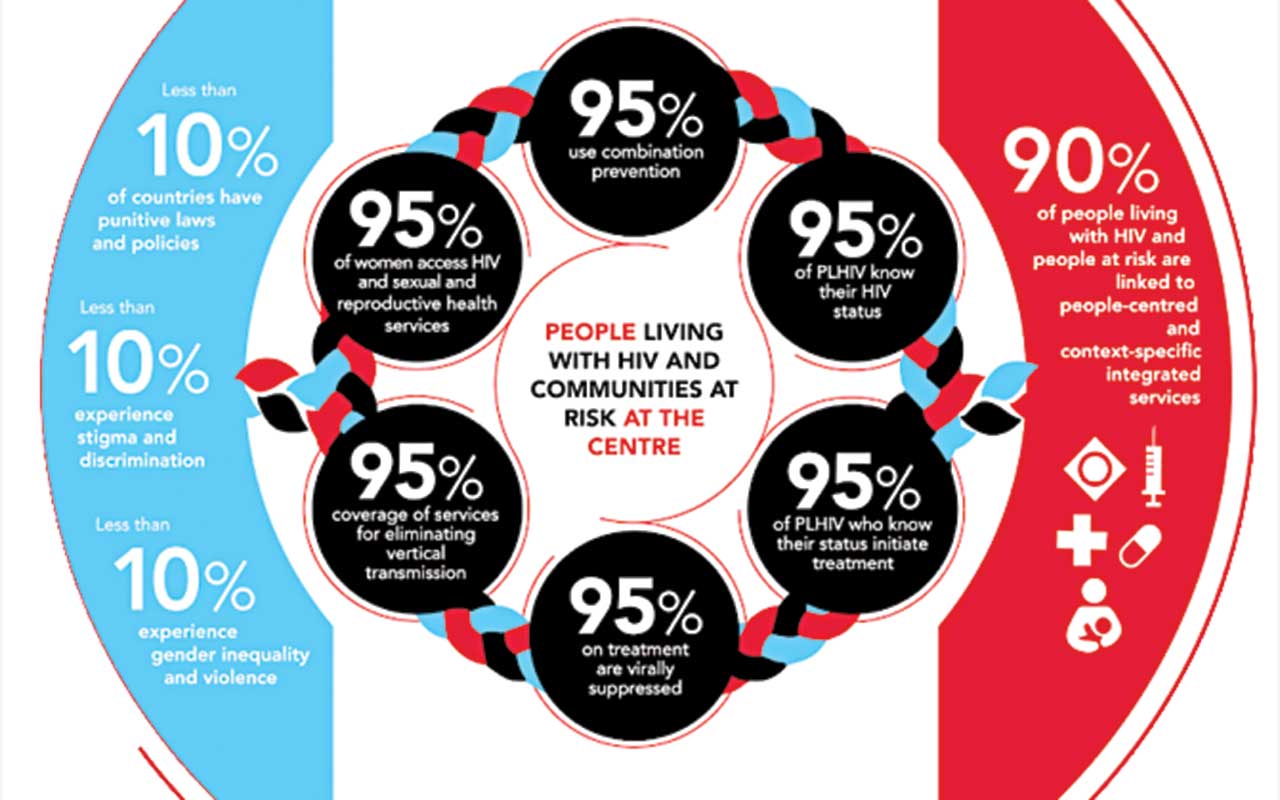

Nigeria’s commitment is anchored on the 95-95-95 goals, which aim that by 2025, 95 per cent of people living with HIV know their status; 95 per cent of those diagnosed are on treatment, and 95 per cent of those on treatment achieve viral suppression.

NACA recently reported that the country is close on two fronts: 87 per cent of people living with HIV know their status, 98 per cent of those diagnosed are on treatment, and 95 per cent on treatment have achieved viral suppression.

Ibrahim, the NEPWHAN chief, agrees with NACA’s claim, saying: “That’s very correct, 95 per cent of those on treatment have already achieved viral suppression. So, that is a good development. But we also need to do more because there are still gaps in identifying people to place them on treatment.

“As of last year, we were quoting the minister that about 1.5 million were on treatment, but as of today, we have about 1.8 million, because the figures keep changing. We are also reviewing the data to ensure that the numbers are correct.”

With scenarios like these, many fear that the country may begin to lose recorded vital gains, especially as disruptions earlier in the year, triggered by sudden funding pauses, exposed the vulnerability of a national response that is still heavily reliant on donor support.

While confidence in the system shook, people living with HIV were left asking the same unsettling question that haunts the likes of Grace Olatokun – What happens if the treatment stops?

This uncertainty took root in January 2025, when the United States, under President Donald Trump’s leadership, paused foreign aid funds, including the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The effect was immediate. Delivery of lifesaving HIV medicines and prevention services faltered across several countries, Nigeria among them, sending shockwaves of panic nationwide. Although a later waiver allowed continued supply of essential medicines, the temporary halt left a lingering sense of instability.

For many stakeholders, it raised an uncomfortable question: “Is Nigeria ready to take full ownership of its HIV response, and can it sustain it?”

That notwithstanding, concerns have again deepened with a new proposal under the UN80 Initiative recommending the “sunset” of UNAIDS by the end of 2026 as part of a broader restructuring of the United Nations system.

A September 2025 report titled “Shifting Paradigms: United to Deliver,” stated plainly, “We plan to sunset UNAIDS by the end of 2026,” outlining an intent to absorb its functions into broader UN development structures from 2027.

The proposal has since sparked alarm among civil society groups, people living with HIV, and several member states.

Critics warned that dismantling the world’s only dedicated HIV agency could reverse hard-won gains and undermine the global goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. They questioned who would assume UNAIDS’ leadership role, safeguard representation of affected communities, or ensure attention to key populations already facing systemic neglect.

Many have also argued that while reform is necessary, the timing is dangerously premature, arriving at a moment when the global HIV response is already strained by mounting funding shortfalls.

For Nigeria, the implications are especially stark. Beyond PEPFAR, the country relies heavily on international support for testing, treatment, and prevention. In 2023, UNAIDS secured $800,000 for Nigeria’s HIV response as part of its global funding commitments; resources that complement other donor streams and help sustain essential programmes. The thought of losing such support, even gradually, has intensified anxieties across affected communities.

Prioritising access to medication, vulnerable populations that bear disproportionate burden

CELEBRATED every December 1st, this year’s World AIDS Day, with the theme “Overcoming Disruption, Transforming the AIDS Response,” urges countries to prioritise innovations that protect and empower communities most at risk.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) said the global HIV response is now at a critical turning point as prevention efforts stagnated in 2024, with 1.3 million new infections recorded worldwide.

According to WHO, data from UNAIDS showed that key and vulnerable populations continue to bear a disproportionate burden, noting that 49 per cent of all new HIV infections occurred among sex workers, men who have sex with men, transgender women, people who inject drugs, and their sexual partners. It also reported that sex workers and transgender women faced a 17-fold higher risk of acquiring HIV, men who have sex with men an 18-fold higher risk, and people who inject drugs a 34-fold higher risk.

It warned that the full scale of recent foreign aid cuts is still emerging, but early indicators suggest severe disruptions.

Citing estimates by the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, WHO noted that about 2.5 million people who used pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2024 had lost access to the medication in 2025 due to donor funding cuts. It said such setbacks could have far-reaching implications for the global HIV response and threaten efforts to end AIDS by 2030.

Following concerns over global disruptions in PrEP access, the former Chairman of Nigeria’s National Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) Task Team, Prof Alani Akanmu, highlighted the critical role of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in reaching populations at the highest risk of HIV in Nigeria.

He said that while PrEP drugs are currently available in government warehouses at a few strategic locations, their distribution remains a major challenge, as the country is still developing capacity for last-mile delivery, previously managed by international partners.

Akanmu stressed that targeted provision of PrEP to LGBTQ+ communities is essential, explaining that although these groups make up less than one per cent of Nigeria’s population, they account for over 20 per cent of new HIV infections.

He added that ignoring these populations would undermine the country’s overall strategy to curb transmission. “I’m able to tell you that this population (LGBTQ+), whether you like it or not, exists in Nigeria, and they are very relevant to the HIV epidemic. For that, one per cent of the population is contributing more than 20 per cent of new infections in the country. And if truly we think we want to end the HIV epidemic, then we cannot neglect to deliver to them all HIV programme services, starting from testing services. It’s not about you condoning the behaviour. It’s their choice of lifestyle. But we are interested in preventing HIV spread,” he said.

Akanmu highlighted that Nigeria’s HIV response relies not only on international support, but also significant domestic contributions, explaining that while U.S. funding covers up to 65 per cent of global HIV programmes, the Nigerian government contributes between 40 and 45 per cent of the cost of running HIV services nationwide.

This support, he said, is often invisible because it does not appear as direct drug procurement, but covers salaries for doctors, nurses, laboratory staff, counsellors, data managers, administrative personnel, and operational essentials like electricity and water, which are essential for keeping ART clinics functional.

Mother-to-child transmission still a sore thumb

IRRESPECTIVE of other efforts aimed at curbing the malaise, persistent challenges in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) could spoil the party, as only about 35 per cent of pregnant women currently access formal health services, although expansion of over 40,000 testing points nationwide has helped raise uptake toward 65 per cent.

The National Coordinator of the Association of Women Living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria (ASWHAN), Esther Hindi, admits that even though significant progress has been made in the HIV response in the country, there are still gaps in the mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

She said, “We are experiencing a lot of progress in the HIV response in Nigeria. We have started seeing the commitment of the government due to the U.S. government’s stop-work order. Mr President has committed $200 million to sustain the HIV epidemic. So, I think that is a plus from our side.

“The association is, however, hoping that the country achieves zero new infection, and then zero transmission from mother to child, as children are still being born with HIV in the country.

“We are talking about overcoming disruption, and one of the disruptions is stigma. Stigmatisation and discrimination are key drivers of these new infections. Most of the time, you see pregnant women who come for the ANC, and after they are tested, instead of going for the treatment, some of them run away and give birth in clinics where their status is not known. So, there are many factors that we might not be able to conclude, but the key driver is stigmatisation and discrimination. We want an end to paediatric HIV in Nigeria.”

Shrinking multilateral support raises treatment sustainability concerns

AFTER a critical overview of the global funding uncertainty, Akanmu is of the view that Nigeria may face reductions in technical support if the United States’ contributions to multilateral HIV programmes such as UNAIDS are scaled back.

While acknowledging that some programme reductions are possible, he stressed that Nigeria now has sufficient local expertise to challenge recommendations that do not align with national realities, even as he argued that shrinking multilateral support underscores the urgent need for stronger domestic capacity and sustainable local funding.

The Association of Community Pharmacists of Nigeria (ACPN), in commemoration of World HIV Day, called for an urgent local investment in HIV/AIDS commodities and services amid donor fatigue.

The national chairman of the association, Igwekamma Ezeh, warned that recent cuts in external funding make local commitment essential and called for government investment in local manufacturing of antiretrovirals, diagnostic kits, and consumables to ensure sustainability, reduce external dependency, and safeguard uninterrupted service delivery nationwide.

According to him, increased local investment and policy commitment are essential to preventing major setbacks in HIV services nationwide. Ezeh described the national HIV response as historically resilient, but cautioned that the current geopolitical and funding environment requires fresh thinking.

“Today’s shifting geopolitical landscape and funding uncertainties demand that Nigeria rethinks, rebuilds, and rises with renewed strategies grounded in evidence-based policymaking, innovation, and multi-sectoral collaboration,” he said.

The Publicity Secretary of NEPWHAN, Lagos branch, Mr Ahmed Salisu, told The Guardian that the central concern for many patients today is the sustainability of treatment.

According to him, the panic that spread earlier in the year when state authorities and implementing partners were instructed to halt support for ART services exposed just how dependent the country remains on external funding and how unprepared many patients are for any abrupt stoppage in drug supply.

Salisu argued that Nigeria can no longer rely almost entirely on donors for its survival and insisted that the government must now fully take ownership of treatment provision.

He warned that many patients already facing unemployment or unstable livelihoods are simply incapable of paying for their medications if the free supply is disrupted. For them, he said, an abrupt break in treatment would be catastrophic.

A particularly sobering perspective comes from the Project Manager at Reach Care Foundation Nigeria, Kayode Emmanuel, who told The Guardian that the country’s recent gains cannot withstand further shocks. His organisation, which expands access to confidential HIV testing and counselling through mobile units, community outreach, and partnerships with local health centres, has seen firsthand how fragile the response remains, especially among key populations who continue to drive the epidemic.

Emmanuel explained that stigma, poverty, and inconsistent access to antiretroviral therapy still define the daily reality for many people living with HIV, while caregivers themselves face emotional burnout and financial strain. These pressures, he noted, often lead to delayed treatment, interrupted care, and heightened risk of drug resistance, outcomes that become far more likely when the wider system is destabilised by funding gaps or supply disruptions.

He added that although Nigeria’s high viral suppression rate reflects the strength of ART when it is available, this success is entirely dependent on consistent medication supply, functioning clinics, and a supported workforce. Any cut to programmes like PEPFAR threatens to erode these foundations, leading to stockouts, reduced testing, and loss of patient follow-up, and can quickly reverse progress and fuel new infections.

For a country with one of the world’s largest HIV burdens, Emmanuel warned that abrupt external funding cuts undermine readiness and risk collapsing the treatment cascade before domestic structures are prepared to take over. Such disruptions, he said, pose an existential threat to the HIV response, jeopardising decades of investment and lives saved.