Towards the end of the 19th century, rampaging British troops looted prized cultural antiques from the Benin kingdom in an invasion that also exiled its monarch. A long running debate on their return is still ongoing.

In 1979, the same year Moonraker – the twelfth movie in the James Bond series – was released, another spy thriller premiered at the Commonwealth Institute in Kensington and National Arts Theatre in London and Lagos respectively. It was titled The Mask.Starring in a lead role as Major Obi, a Nigerian army detective and spy, was its executive producer, 39-year old Eddie Ugbomah. Other characters included Dele Osawe – who would later go on to play Teacher Fadele in the local TV series, Village Headmaster – and Mark Heath, the Jamaican actor popular for his role as the dictator Idi Amin in the 1977 crime flick, Entebbe: Operation Thunderbolt.

The suave major found time while kissing and smooching beautiful British babes, to invade the British Museum in London with foreign mercenaries and retrieve an original ivory pendant mask – one of the original Benin Bronzes. Some scenes were shot in the actual London museum. It was like pulling a James Bond on the homeland of – and the very intelligence that birthed – the fictitious secret agent.

The Benin Bronzes were prized treasures that had been taken from the old Benin Empire in a punitive expedition by a 2,600-man strong force plus in 1897.This was during the reign of Oba Ovoramwen who was exiled eastwards to the city of Calabar. Various accounts have put the total number of bronzes as anything between 3,000 to 6,000 pieces.One of them – the ivory pendant mask retrieved in The Mask – had been selected as the insignia of the second pan-African Festival of Black & African Arts & Culture (FESTAC) held in Lagos from January-February 1977. A year before, Lagos had pleaded with London to release the original, an exquisite carving of Idia, the first ever queen mother of the ancient empire. Her son Esigie had created the office to honour her for helping him in successive victories against his brother Arhuaran – after the death of their father, Oba Ozolua – and the Igala from across the River Benue. Consequently, her image was carved onto an ivory mask.

All entreaties to Britain to return the spoils of war fell on deaf ears, including a desperate offer of two million pounds (£2m) to rent the item for the duration of the festival. To avert a national embarrassment, then head of state Olusegun Obasanjo on advice of Oba Akenzua II, the then Benin monarch, commissioned a local carver, Joseph Igbinovia Alufa to produce a brilliant replica.

The background controversy buoyed sales of The Mask, making it an instant hit. Shot on 35mm, it was well distributed across also the United Kingdom, triggering a flurry of reactions from the British press as well as a diplomatic rift of some sorts between both countries.

“The film was motivated by the British government’s snubbing our requests for the return of the mask”, Ugbomah recalls from the comfort of his compound at Badagry, near the Nigerian border with the Republic of Benin. “Being a filmmaker and knowing the power of movies, I shot this film. One of the things which it did for Nigeria and unfortunately which the Nigerian government did not appreciate, was that as soon as it was released, the British media became afraid. In the film, we broke into the actual museum and so there was fear.”

In the aftermath, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) commissioned a documentary on colonial-era artefacts. In it were several agitators for the repatriation of looted artefacts alongside Ugbomah. One was Oscar-nominated singer and actress Melina Mercouri, who later became the first Greek female minister of culture. For years, she had been a staunch advocate for the return of the famed Pathenon marbles (called Elgin marbles after the seventh Earl of Elgin and British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire who stole them in 1811).

The Nigerian government took advantage of the dust that had been stirred up and successfully negotiated the release of some other artefacts in British possession through Eyo Ekpo, head of the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments at the time. But the headstrong British government particularly refused to release the Benin Bronzes, saying they were “too delicate to be returned”, Ugbomah recalls.Four decades later, the filmmaker, his celebrated movie and the underlying subject of the bronzes have all slipped out of the mainstream and under the radar.

Once Upon an Empire…and an Expedition

Established in the 13th century, the old Benin Empire blossomed between the 14th century and the 16th centuries. By this time, it had a relationship with Portugal, receiving missionaries from there and sending an ambassador to the capital city of Lisbon. According to foreign traders who visited, it was a well-structured kingdom.

At the peak of its dominance, the influence of the empire is believed to have stretched to present-day Ghana and Togo, areas east of the River Niger and westwards in what is today southwest Nigeria. During a spell of territorial expansion in the mid-15th century, it founded Eko, a war camp near The Atlantic Ocean. This camp was renamed Lagos by Portuguese traders in the 17th century.

The Binis controlled trade in palm oil, ivory, timber, rubber, slaves and other commodities. They also taxed merchants along the Benin River through established middlemen like Chief Nana Olomu of Koko, governor of the Benin River District. His deposition and exile during the British-induced Ebrohimi Expedition of 1894 and subsequent dismantling of others like him, coupled with internal political conflicts helped weaken the empire’s position.

Two years before Nana’s fall, a British delegation led by Captain Henry Lionel Gallwey, vice-consul of the Oil Rivers Protectorate visited Oba Ovonramwen with plans to annex Benin and sign the Anglo-Benin Treaty of 1892. A controversial treaty, it was found to be deceitful by the royals after it had been signed. Consequently, the king issued an edict banning trade with the British and their entry into the empire. The aliens waited patiently and struck Brohimie, Nana’s enclave in 1894. With the chief trader in the area gone, the British forces began to plan a takeover of the entire empire.

The fall of Nana necessitated the strengthening of security around the southern border and the Benin Empire swiftly did so. Between 1895 and 1896, colonial officers asked the Foreign Office in London three times for a military invasion of Benin Kingdom, but London withheld consent.But fortune favours the persistent and fate soon served up a juicy opportunity for the colonialists. In March 1896, the Oba of Benin ordered a trade embargo after the middlemen tried to fix prices rather than allow a free market. Seven months later, the now infamous Captain James Phillips, then acting in the capacity of consul-general of the Niger Coast Protectorate, held meetings within the Benin River area, consulting with traders and secretly planning to invade the empire, with or without permission.

In December 1896, an impatient Phillips proceeded with a convoy of 230 local carriers, and eight British officers and traders for a visit to the Oba of Benin. Phillips’ party had been warned not to visit the capital specifically around that period; the Igue festival was on and foreigners were not permitted to enter the capital then. Like the stubborn fly that goes into the grave with a corpse, he proceeded anyways, ignoring advice of his spies. Itsekiri chiefs messaged the Oba about the impending arrival of a white man who was bringing the gift of war along with him.

The Oba’s council convened after getting the message. They wanted to kill Phillips and his men but the monarch was cautious, preferring to wait till the visitors got in first and then ascertain their intentions later. But his prime minister, the Iyase was distrustful of the travelling party. Being a man of war and not of words, he sent warriors to ambush the British and kill them in the village of Ugbine, just outside the capital. The warriors were led by the Ologbosere, a senior army commander.

Only two whitemen escaped. This unfortunate episode now referred to as The Benin Massacre, was the thunder before the rain; the forerunner of a bigger tragedy to come. The British government launched a military offensive. In January 1897, a strikeforce of 1,200 men left the shores of Liverpool, joined by 2,000 local carriers. They landed near Benin City.

The “Punitive Expedition” began on February 9th, but it was not until the 18th that the invaders gained access, after looting and killing their way through the kingdom to the capital. Centuries-old art in the palace including about 3,000 bronzes with transgenerational stories of the kingdom carved on them, were looted and the city set aflame. Ovonramwen himself was exiled to the port town of Calabar after being acquitted and exonerated in a trial.

The British victory was a cause for enthusiastic celebration back home; Queen Victoria herself congratulated the Royal Navy and the newspapers published special editions of stories about putting an end to a barbaric African kingdom, portraying the pogrom as a response to a barbaric act. However, evidence that it was a premeditated action came to the fore in a letter by Phillips dating back to 1896. According to an extract from a lecture by P.A. Igbafe, professor of history at the University of Benin on the centenary of the tragedy in February 1997, Phillip wrote: “I would add that I have reason to hope that sufficient ivory would be found in the King’s house to pay the expenses incurred in removing the King from his stool.”During its time as a colonial powerhouse, Britain also looted artefacts from other countries including India, Greece, Australia, China, Kenya and Egypt.

The Gift That Keeps on Giving

On the troops’ return, most of the looted art were auctioned off to museums and private collectors in Europe to defray the costs of the war. Some went to the queen, some went missing during World War II and some were re-looted but a few remained in the hands of the soldiers themselves as spoils of war.

There are approximately 700 Benin pieces at the British Museum in London alone – the largest collection worldwide – and about 550 pieces in the Ethnological Museum, Berlin. Other originals lie randomly in museums in Boston, Vienna, Cologne, Hamburg, New York, Oxford, Paris, Stockholm, Leipzig and other far-flung places across the world. Only few are in museums in Lagos, Jos and Benin City.

In 2016, students at Cambridge University voted overwhelmingly to return Okukor, a bronze cockerel taken during the punitive expedition and placed at the entrance to one of its dining halls. One comment piece in Varsity, the student newspaper exclaimed, “Benin Bronzes can only be viewed as a symbol of Britain’s historical hooliganism and torment of Nigeria!” In response, the authorities removed the art.

But that wasn’t the end of the debate. In March 2016, The Daily Telegraph published a letter from a wealthy alumnus demanding that the cockerel be put back up or he would cut the Jesus College of the university out of his will. He claimed that college authorities had given in to the “silliness of undergraduates,” and that a “sterner approach” was needed. The fate of the cockerel remains unresolved even as it lies in storage at the British institution.The estimated value of all the bronzes is put at over $1billion in total, according to various people in the know. In 2007, a private collector paid $4.7 million for one at Sotherby´s, the British art corporation headquartered in New York.

In the New York Times archives are advertorials for auctions, some dating back to the early 1900s, where private collectors bought what editors called primitive or tribal art, for huge sums. “A Benin bronze head of a king, cast before 1550, was sold yesterday at Christie’s in London for $2.08 million, a record in auction for tribal art”, began a July 5, 1989 article in its arts section.

With millions in revenue generated and more to be earned from putting the bronzes on display for tourists to view and charging hundreds of dollars per view, will museums and their governments eventually let go of the artefacts?

The Great Debate

Since Ugbomah in the ‘70s, there have been series of calls and lobbying for the reparations of the bronzes. Only a few have been returned to Nigeria since Ekpo’s negotiations around the same period. Some Western museum curators have (openly and in background talks) dismissed Nigeria as being too corrupt and having lax security and professional standards at its museums.Herbert Walker, one of the officers who went on the expedition, had left a diary and kept two of the artefacts for himself – an Oro ‘bird of prophecy’ and a bell used for ancestral summons. His grandson Mark, born fifteen years after his death, inherited them. In 2014, he travelled to Benin to hand over both items to the then Oba, great-grandson of Ovonramwen.

In November 2017, Emmanuel Macron, president of France visited Burkina Faso, a former French colony in West Africa. “I cannot accept that a large part of cultural heritage from several African countries is in France”, he told students at the state-owned university in Ouagadougou, the capital. “African heritage can’t just be in European private collections and museums. African heritage. In the next five years, I want the conditions to be met for the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage to Africa.”

If Macron´s statement was meant to spur international curators to action, there is no evidence that it is working. The Benin Dialogue Group, a consortium of museums, has been making plans to ‘loan’ the bronzes back to Nigeria since 2010. As at the time of this report, nothing has been concluded, leading to speculations about the group’s sincerity.

The British Museum in London has a wall filled from top to bottom with bronzes. The audio guide in that section announces with a healthy dose of euphemism that when British troops arrived in the Kingdom of Benin in 1897, they “discovered” almost a thousand of these relics “hidden away in a storeroom”.

“I don’t consider these issues particularly complex”, posits Christopher Marinello 55, a popular Venice and London based art detective known in art circles as the ‘Robin Hood of art’ for his specialty in retrieving Nazi-looted art. “What is complex is dealing with those individuals and institutions who don’t want to cooperate with restitution for financial or proprietary reasons. We can only imagine what this part of Africa would be like today without the cultural rape of this civilisation that took place in 1897.”

Since April 2017, 54-year old Barbara Plankensteiner has been the director of the Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg which holds around 150 of the bronzes. Ten years before, she curated an exhibition on Benin at the Museum of Ethnology (since renamed the World Museum) in Vienna; it was also shown in Paris, Chicago and Berlin. Plankensteiner brought together key Benin key works from museums in several European museums and was able to involve the Nigerian government and the Benin royal family.

Plankensteiner and her Nigerian colleague Nath Mayo Adediran wondered whether it might be possible to put on such an exhibition in Nigeria too. In 2010, she organised a meeting of European and Nigerian experts in Vienna to, in her words, “discuss the various parties’ expectations”. The Benin Dialogue Group had a second meeting in Berlin in 2011. A third followed in Benin City two years later, where the “Benin Plan of Action for restitution” was adopted. The document did not deal with restitution at all.

“At the moment, the discussion is about long-term loans,” says Plankensteiner who reiterates that investment is needed in Nigerian museums. She hopes to find an international donor to support the Benin project, she adds. “We all have our own funding issues to deal with which makes it hard to come up with extra money for a project like this.”

Three of the bronzes are on display in the Hamburg museum’s exhibition “Africa’s Top Models”, with the slogan “young, potent, incredibly beautiful”. The rest of its extensive Benin collection is in storage. According to Plankensteiner, they will appear in the permanent exhibition following its refurbishment. But when will that be? For 20 years, the museum – described as “one of Europe’s leading ethnographical museums” – hasn’t even been able to afford a dedicated curator for its Africa collection.

The Berlin museum has the world’s second-largest collection of Benin objects, around 550 in total. Originally founded in 1873, the museum has been closed since January 2017 due to a planned move from its current location outside the city centre to a new location, the Humboldt Forum in the newly rebuilt Berlin Palace. Half a billion euros have been invested in the palace as part of plans to establish Berlin as “one of the world’s leading centres for culture and museums”. Activists have organised demonstrations and panel discussions, claiming that the new concept for the Humboldt Forum, which they label “eurocentric” and “restorative”, infringes people’s dignity and ownership rights. It is a debate being followed closely by museum curators and directors all over the world.

In exile, the Benin Bronzes seem like mere relics from eras long past. Back in Nigeria, the debate is not purely academic and are triggering post-colonial trauma. Nigerian superstar Adekunle Gold’s music is mellow, but when he speaks of the bronzes, his words are harsh: “How can it be that I have to fly to London to look at something that belongs to my culture, that was stolen from us?”, says the 30-year-old musician just before he sets out on a trip to New York.

Born and bred in Benin, Victor Ehikhamenor is one of Nigeria’s best known visual artists. His reaction to the debate on the bronzes is one of indignation, not much different to his stance in a similar debate last summer. One of the artists representing Nigeria in its debut at the Venice Biennale, he was embroiled in a row over cultural appropriation after visiting an exhibition of another famous artist, Damien Hirst. Ehikhamenor recognised a sculpture from his native country: Hirst had modelled his work on the Ife head but without proper mention of its origins. The Nigerian took to Instagram to voice his indignation, stimulating a viral debate.He remembers seeing the bronzes for the first time years ago in London. “I almost cried”, he reminisces in his studio in the upscale Ikoyi neighbourhood of Lagos. “It was overwhelming …1897 was an economic war against us too. And it’s still ongoing today. “

Museums generate a lot of income from tickets from tourists, catalogues and image rights. Ehikhamenor believes this is yet another reason why the bronzes should be returned to their country of origin. But he believes the Nigerian government has obligations it must fulfil too. “If we want to bring them back, we need to give them a place where they can be displayed and conserved properly.”

East or West, Home is the Best

A former Nigerian ambassador to Sweden and Italy, the Oba Ewuare II of Benin ascended to the throne in 2016 after the death of his father, Erediauwa. “The looted artefacts are very very important to us; they are of deeply religious importance to the place and to my people”, he explains at his palace, 300 km east of Lagos.While studying for a master’s degree in public administration in New Jersey, his father sent him as a representative of the royal family to Philadelphia, where he visited a museum. The then prince was stunned about the bronzes he saw in its heavily secured basement. He found a shrine as “our ancestors used it, and how we use it here in the palace today.” During his diplomatic missions, he asked on various occasions about their homecoming, to no success. Yet he remains undeterred in getting some of the antiques back.

“I say deliberately we want ‘some’ of the looted objects back, not all. Because they have become ambassadors of our culture around the world”, explains the king. “We prefer that they come back to the owners of the artefacts that were looted, back here to the palace. We are planning a palace museum, where the pieces that come back to us will be very save and accessible to visitors.”

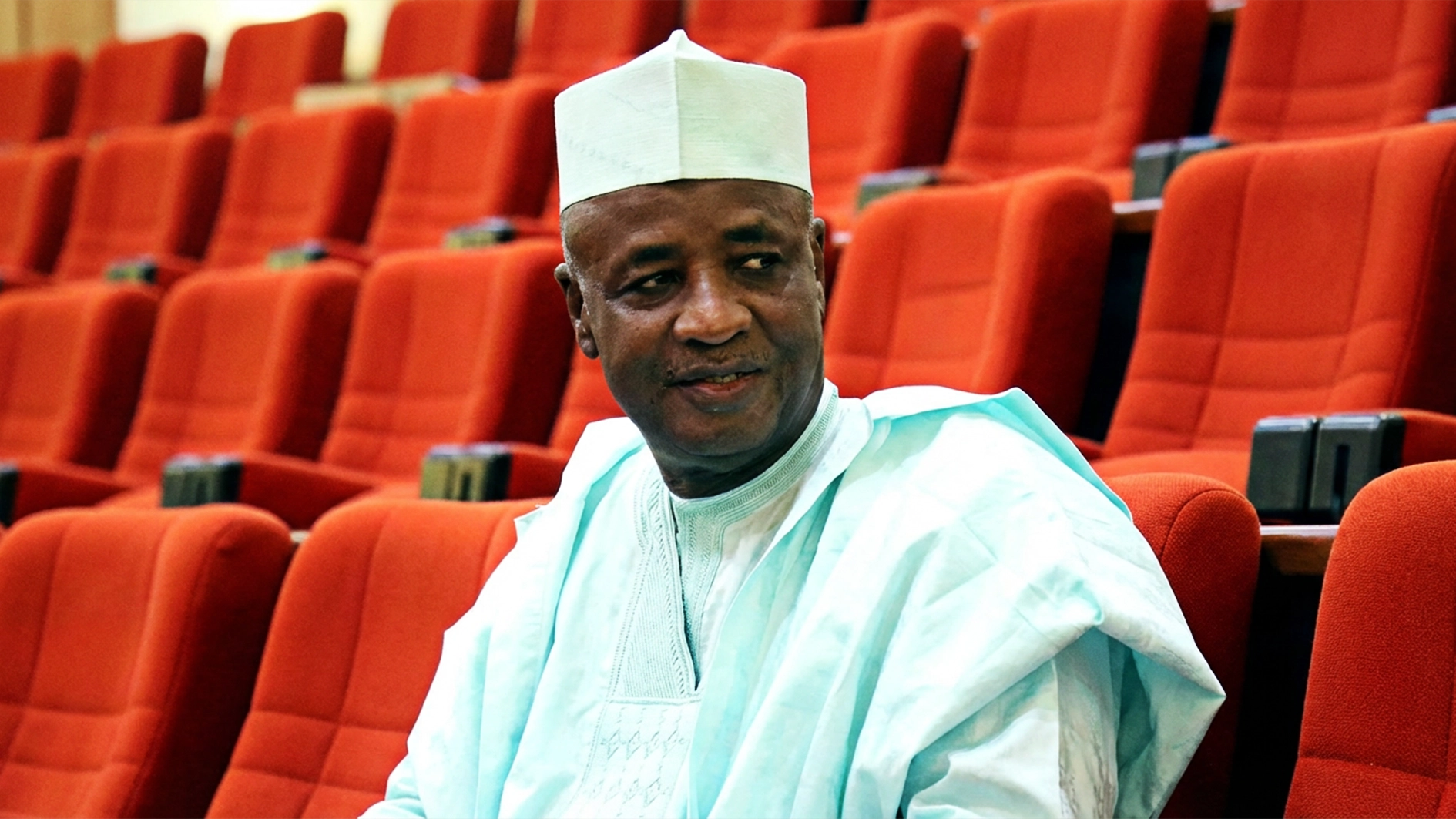

For Godwin Obaseki, current governor of Edo state of which Benin is its capital, the Benin Bronzes are top priority. “These artworks embody who we are: our people, our culture, our religion, even part of our political structure,” he says, during a brief interview in his office. “A hundred years ago, they were brutally snatched away from us, and we’re still trying to get them back. The events of 1897 traumatised our entire people…don’t forget that Benin was once a world power.”To foster healing for the lingering trauma, he is working in tandem with the Oba to build a world-class museum. “The decision to establish a world-class museum at the Oba’s Palace, one of the safest places in the world, will encourage curators across Europe and in other parts of the world, to be confident and support the advocacy for the safe return of stolen artefacts of Benin Kingdom”, he told visitors from British universities in April 2018.

All the main roads in Benin City converge on King’s Square, a giant traffic island ringed by a roundabout in the heart of the city of 1.5 million people. The square is the site of the recently refurbished National Museum, housed in a cylindrical-shaped building. Museum guide Ikhuehi Omonkhua’s tour of the kingdom’s history takes an hour. Within are plinths, wall displays, bronzes and replicas, sculptures of various Obas and queen mothers, full-wall historical photographs of the British invasion and more. On the second floor is an exhibition on Solomon Osagie Alonge (1911–1994), a photographer from Benin City.

The exhibition, a gift from the Smithsonian Institute which holds several of the looted antiques, ran in Washington D.C. from 2014-2016. It is the first exhibition of the world’s largest museum in Africa. At the opening ceremony, Oba Ewuare II met with the American ambassador to Nigeria, Mr. Stuart Symington, expressed gratitude for the financial assistance in refurbishing the museum but reiterated his demands for restitution.

“We’ve invested a lot and brought the museum back up to scratch,” gesticulates Theophilus Umogbai, curator of the museum. “The government of Nigeria wants the looted objects back. As a museum man, I shouldn’t be so emotional, but I can’t help it”. It is wrong to punish a whole society because a few works have been stolen from Nigerian museums by criminals, he adds.

His response to the argument by Western curators that Nigeria would not be able to properly preserve the artworks if they were returned is a dry, bitter, curt laughter. “These objects were in our possession for over 500 years before the British looted them. So, don’t worry.”

Prince Edun Akenzua, brother of the late Oba and uncle of the current one agrees with the local curator. In 2000, he gave an address to the British House of Commons in one of many unsuccessful lobbying attempts to regain them. His response to concerns on safety of the items back in Nigeriais a calm but emphatic analogy. “That’s like having your car stolen, tracking down the thief and demanding it back, only to be told that the new owner is looking after it much better than you, and you need to build a garage first before you can get it back.”

This article is part of the Benin-Bronze-Project, a collaboration between German newspapers Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Leipziger Volkszeitung and Code for Nigeria. Other contributors include John Eromosele, Emmanuel Ikhenebome and Maria Wiesner. It was financed by the German journalist Association and its Carthographer-Mercator-Programme for Journalists.

[ad unit=2]