In 1840, in South Carolina, United States, a former slave while on his deathbed instructed his sons to return to his native land in Africa.

The man, Scipio Vaughan who was originally from Owu kingdom of Abeokuta in Nigeria was captured by European trans-Atlantic slave traders in 1805 and was taken together with other captured slaves to the Velekete Slave Market in Badagry, one of Nigeria’s slave portal, from where he was shipped in a slave ship to America.

[ad]

In America, he was sold as a slave to Wiley Vaughan, a white master who brought him to live in Camden. As per the prevailing tradition, he took the surname of his master in addition to his given name; Scipio, as Scipio Vaughan. Scipio was so skilled as an ironmonger that he earned a reputation in the area as a talented artisan for his work in fashioning iron gates and fences. As a result of his exceptional gifts, master Wiley Vaughan valued him so much that, as stated in his will, he granted him one hundred dollars, his tools and his freedom.

Decades before the 13th amendment abolished slavery in the United States, a number of freed slaves were already living in the country. Although free, they were not recognised as citizens, and had no legal rights. They were seen as racially inferior. No one wanted them as a part of the American society. Slave owners didn’t want them in America as they were seen as a threat to their business. Even the abolitionist – majorly whites – who wanted the slaves to be free, believed that blacks could not achieve equality in the United States. The freed slaves simply had no place in America.

The question that bothered the white populace, therefore, was “what do we do with them?”

The suggested solution to the problem was to move free slaves away from America to places where they would enjoy greater freedom.

In 1816, the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, commonly known as the American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded. The purpose of the group was to encourage and support the migration of free African Americans to the continent of Africa.

And so began a cause that came to be known as the Back-to-Africa movement, or Black Zionism or Colonization movement. The goal of the movement was to resettle the freed slaves in Africa. The movement, however, was a colossal failure as few freed slaves wanted to move to Africa, and those few that did – some under duress – faced brutal conditions.

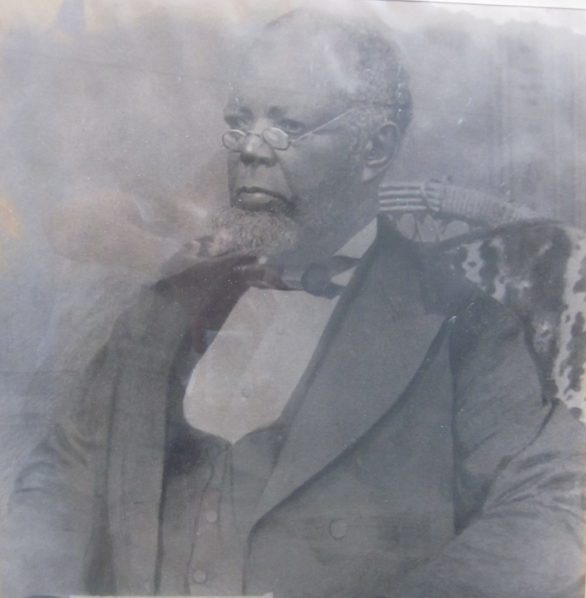

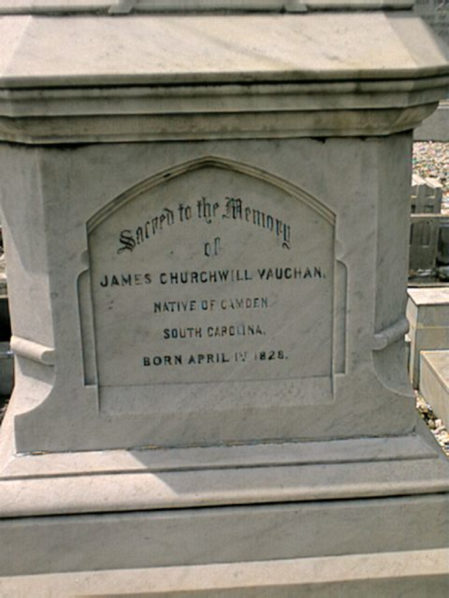

In the midst of that failure, a man’s dying wish however survived. In 1852, 24-year-old James Churchwill Vaughan and his elder brother Burrell Vaughan, the sons of Scipio Vaughan, left America for Liberia where they became prominent.

Three years later, James Churchwill Vaughan joined a group of Southern Baptist missionaries who were passing through Liberia on their way to spread the gospel in Yorubaland.

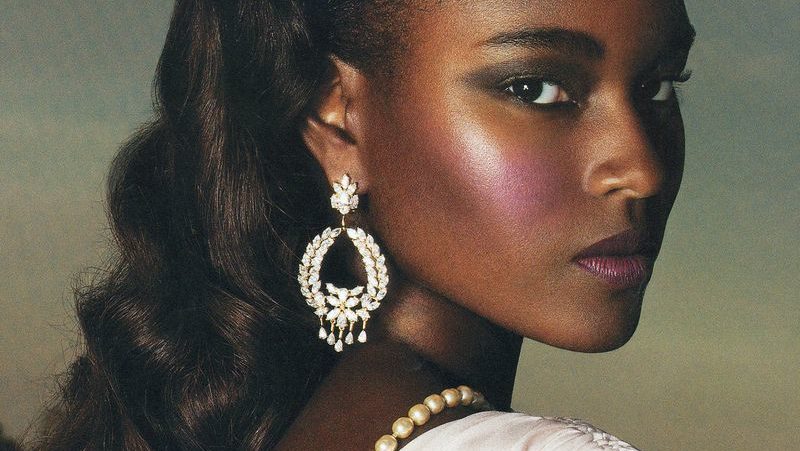

After missionaries were driven out of Abeokuta in 1867, he and other Christian refugees resettled in Lagos, where he built a successful hardware business and raised his family.

He became part of the Lagos elite and was a wealthy and prosperous merchant. He also led a revolt against white missionaries, in the 1880s, helping to establish the Ebenezer Baptist Church, the first indigenous and independent church in West Africa in 1888, located at 50a, Campbell Street, Lagos Island.

James Vaughan kept correspondence with his American family. Even after his death his children remained connected to their American relatives.

Members of the Vaughans of Nigeria and the United States have maintained contact with one another for several decades over the century.

From the deathbed of Scipio Vaughan, today his last wish has survived and grown into a network of more than 3,000 cousins American Vaughans from over 22 states – along with their Nigerian cousins.

[ad unit=2]