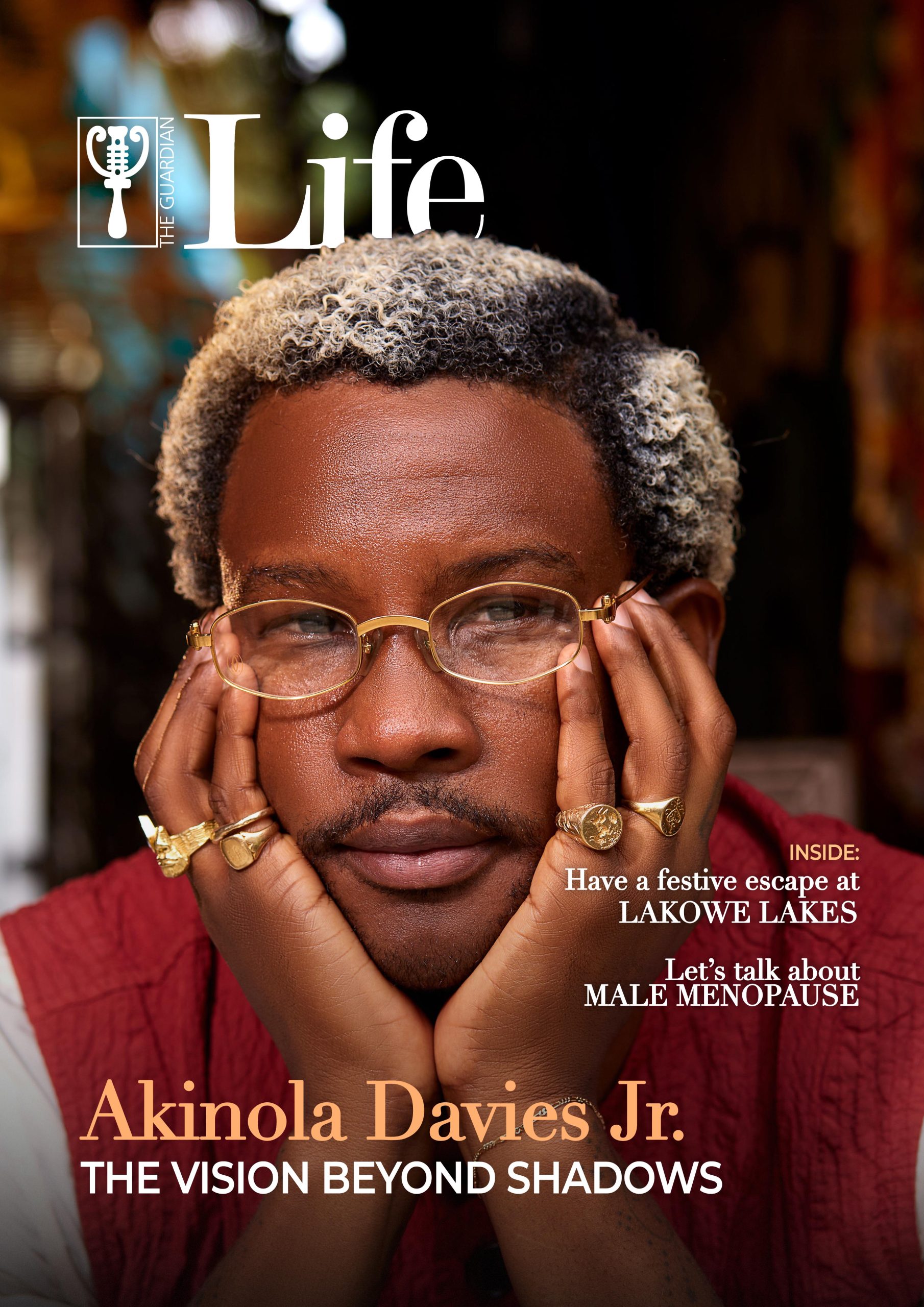

Nigerian Fresh from his historic Cannes win, My Father’s Shadow director Akinola Davies Jr. returns to Lagos with a story rooted in family, memory, and truth. Now, as the UK’s official Oscar submission for Best International Feature, the British-Nigerian filmmaker reflects on home, heritage, and the honest storytelling reshaping Nigerian cinema.

Home has a way of calling you back, whether as memory or mission. When My Father’s Shadow premiered in Lagos, the applause it received felt like a homecoming long overdue. For Akinola Davies Jr., the British-Nigerian director behind the historic Cannes winner, the moment felt like both an arrival and a reminder that Nigerian stories, told with honesty and care, could travel the world and still come home whole without losing their roots.

“I think it’s like a homecoming that’s well deserved,” he said, visibly proud to be back in the city that shaped his story.

A few months later, that same story would carry his name to the Oscars, as the United Kingdom’s official submission for Best International Feature at the 98th Academy Awards.

The story behind My Father’s Shadow

When Akinola speaks about My Father’s Shadow, he does it with the kind of easy calm that comes from telling a story you’ve lived.

“I made a short film in 2020 called Lizard, which won the Grand Jury Prize in Sundance,” he said. “Me and my brother realised we’d have an opportunity to make a feature film, and we decided to make something about our childhood growing up here in Lagos.”

Co-written with his brother, Wale Davies, the film grew out of a shared desire to revisit a childhood that existed in fragments that come after loss. “The inspiration was [Wale] wanting to spend the day with him, ask him questions, get to know him basically,” Akinola recalled, speaking of their late father who died when they were kids.

Set on June 24, 1993, the day Nigeria’s presidential election was annulled, My Father’s Shadow follows a father and his two sons as they move through Lagos trying to collect unpaid wages while the country teeters on unrest.

But for Akinola, the film’s political context was secondary. “Really, that’s a side of the film,” he said. “The main aspect was the idea of spending the day with our father, getting to know aspects about his personality. We wanted to make something that would honour our childhood, honour where we grew up, and honour Nigeria.”

The collaboration between the brothers was instinctive and rode on each’s strength. “We grew up together, we have very similar interests, and we just like spending time with each other,” he said. “He’s a very good writer, I think more with pictures, so there’s a separation of how we like to work. But ultimately, we just bounce ideas off each other.”

The result is a film that feels deeply intimate and unforced. It’s a portrait of family, absence, and the small ways memory keeps love alive.

Lagos on film

Few cities know how to command the camera quite like Lagos, and Akinola Davies Jr. knows it well enough not to frame its vicissitudes. “Lagos can be a very chaotic place, can be a very calm place, and I think that mirrors the people that live in the city,” he said. “So, it was important to capture the essence of the place we live in and capture it as honestly as possible.

In My Father’s Shadow, Lagos hums like a character of its own. The streets feel lived in, the camera unhurried, the tension constant yet tender. It’s the Lagos we recognise from experience as it is, without exaggeration, full of contradiction and beauty.

Shooting it, though, came with challenges. “If you see the film, almost every scene is a challenge,” Akinola said with a laugh. “We shot on Third Mainland Bridge, which we prepared for weeks because it requires logistics. We have children, we have moving parts, we have cameras. But when it came down to shooting, we were done in like 20 minutes. Everybody was so prepared that we got what we needed in one or two takes.”

That discipline, he says, came from experience. “We’ve been shooting in Nigeria for like 10 years. We work with Area Boys, our crew. We have to find a way to integrate them into what we’re doing. Otherwise, we cause problems for ourselves. The product we’re making should be accessible to everyone.”

It’s this commitment to working with local hands, local knowledge, and real people that gives the film its texture. The Lagos he captures becomes both stage and collaborator, breathing life into the story.

From Cannes to the world

When My Father’s Shadow premiered at Cannes, it became the first Nigerian feature to screen in the festival’s Official Selection, and went on to win the Special Mention for the Caméra d’Or. It was a moment that stretched far beyond red carpets or applause. “I hope that they feel it’s an honest portrayal of what it is like to be Nigerian and the sort of hurdles that life throws at you,” Akinola told AFP.

Critics saw it as a breakthrough for Nigerian cinema, often overlooked on the global stage despite its huge intercontinental appeal. “This is not the kind of movie that you see all the time here in Nigeria,” said fellow director Nicolette Ndigwe in an interview with AFP. “My Father’s Shadow bucked the industry’s fear of not having the market for arthouse films. It’s a breath of fresh air.”

At home, the response was emotional. Families saw themselves in the story, not the polished, overplayed versions of Lagos life, but the quiet, everyday truths. Abroad, it was hailed as proof that Nigerian films could be home-rooted and universal at once.

Months later, when news broke that My Father’s Shadow had been selected as the United Kingdom’s official submission for Best International Feature at the 98th Academy Awards, it felt like the journey had come full circle.

The success, Akinola insists, is a shared one. “The future is to keep producing work in Nigeria that can hopefully sit on that global stage and tell Nigerian stories 100 percent,” he said.

It’s a simple dream, but one that now feels closer than ever. This milestone is for him, his brother and the new generation of Nigerian filmmakers learning that art and authenticity can coexist and win.

Growing while staying grounded

For all the praise My Father’s Shadow has received, Akinola Davies Jr. insists the spotlight doesn’t belong to him alone. “The director often gets all the praise. The director gets all the interviews, for example, but I couldn’t have done it without the crew,” he said. “It’s a testament to the fact that if people on the ground here are supported, if they’re given the resources, if they’re given structure, we can make incredible art together that can travel around the world.”

He talks about his team with affection; the technicians, the extras, the young actors are all part of the tapestry that brought the film to life. “The crew is really important for me,” he said. “I try and centre them as much as possible because the director is only one person, but the crew is so many people. What we want to do is just keep growing and keep educating the crew so that we can make more and more films together.”

“The main responsibility I feel is just to show up for myself, show up for my community, show up for the people I’m trying to project in the film,” he said. “I don’t want to create something that’s a complete fallacy and broadcast that to the world. We do a lot of research, we do a lot of history, we speak to a lot of people when we’re making our film just to make sure that we don’t have any blind spots.”

That honesty anchors his work. His art is collective. His success, shared. And his sense of pride extends to everyone who helped turn a deeply personal story into a piece of cinema that belongs to all of us.

That word, growing, comes up often when he speaks. “I would say I’m still growing, to be honest. Every day you do something, you get more experience. I’m trying to work with collaborators, learn from people who have been doing it longer than I have, and listen.”

It’s not just a reflection of his own process; it’s a message to the next generation. “I hope that they’ll see that their voice is important,” he said. “That Nigerian stories can exist on the world stage.”

Because for Akinola Davies Jr., filmmaking isn’t about chasing shadows of validation. It’s about light, and memory, and home, and how much further Nigerian cinema can go.