On 18 March 2025 President Bola Tinubu declared a six-month state of emergency in Rivers State — an extraordinary federal intervention that included the suspension of Governor Siminalayi Fubara, his deputy and the entire Rivers State House of Assembly and the appointment of retired Vice-Admiral Ibok-Ete Ibas as sole administrator. The proclamation followed months of bitter intra-party conflict between FCT Minister Nyesom Wike and Governor Fubara, episodes of legislative paralysis, and a string of pipeline attacks that threatened Nigeria’s oil lifeline. The emergency expired in mid-September and elected officials were restored — but the political, economic and institutional aftershocks remain.

Background and timeline

The immediate trigger for federal action was a breakdown in Rivers’ executive–legislative relationship. Lawmakers aligned with one faction moved to impeach the governor amid accusations about budgetary irregularities and control of appointments; the situation deteriorated into street confrontations and disruptions of government business. At the same time, sabotage and fires on key export pipelines — whether opportunistic criminality or politically motivated attacks — reduced throughput and alarmed Abuja, which framed the intervention as necessary to protect national assets. The state-level dispute therefore morphed into a national security and economic problem.

What the emergency did — and did not — achieve

Federal insertion bought time to secure critical infrastructure and temporarily halted the institutional stand-off that had frozen governance. By placing a sole administrator in charge, the centre could coordinate security responses, fast-track repairs and re-establish a chain of command around oil protection. However, emergencies are blunt instruments: they suspend democratic accountability mechanisms, inflame narratives of federal overreach, and do not by themselves resolve the underlying political fragmentation or the root drivers of pipeline crime. The decision therefore traded immediate stability for long-term political risk.

Implications for Rivers and Nigeria’s oil economy

Rivers State sits at the centre of Nigeria’s crude production and export system. Even temporary disruptions translate into lower export volumes, delayed royalties and higher costs for oil companies — effects that cascade into national revenue shortfalls and currency pressure. The March intervention followed a period when operators reported pipeline fires on lines such as the Trans-Niger route; each incident reverberates through investor risk assessments and the logistics of crude evacuation. Moreover, militarised security responses can suppress some theft and vandalism but often fail to address local grievances that drive sabotage: grievances over jobs, environmental damage, and the opaque allocation of oil rents.

Legal and constitutional questions: precedent and controversy

Section 305 of the 1999 Constitution provides for emergency proclamations, subject to National Assembly approval; yet deploying emergencies against a sitting governor is intrinsically controversial. Critics argue that suspension of elected officials without impeachment or judicial adjudication risks normalising federal override of subnational democracy. Supporters insist the move is constitutional when the state’s breakdown constitutes a threat to public order or critical national infrastructure. The Rivers episode has thus reopened a long-running national debate about the balance between state autonomy and federal responsibility in crises.

Political fallout and party dynamics

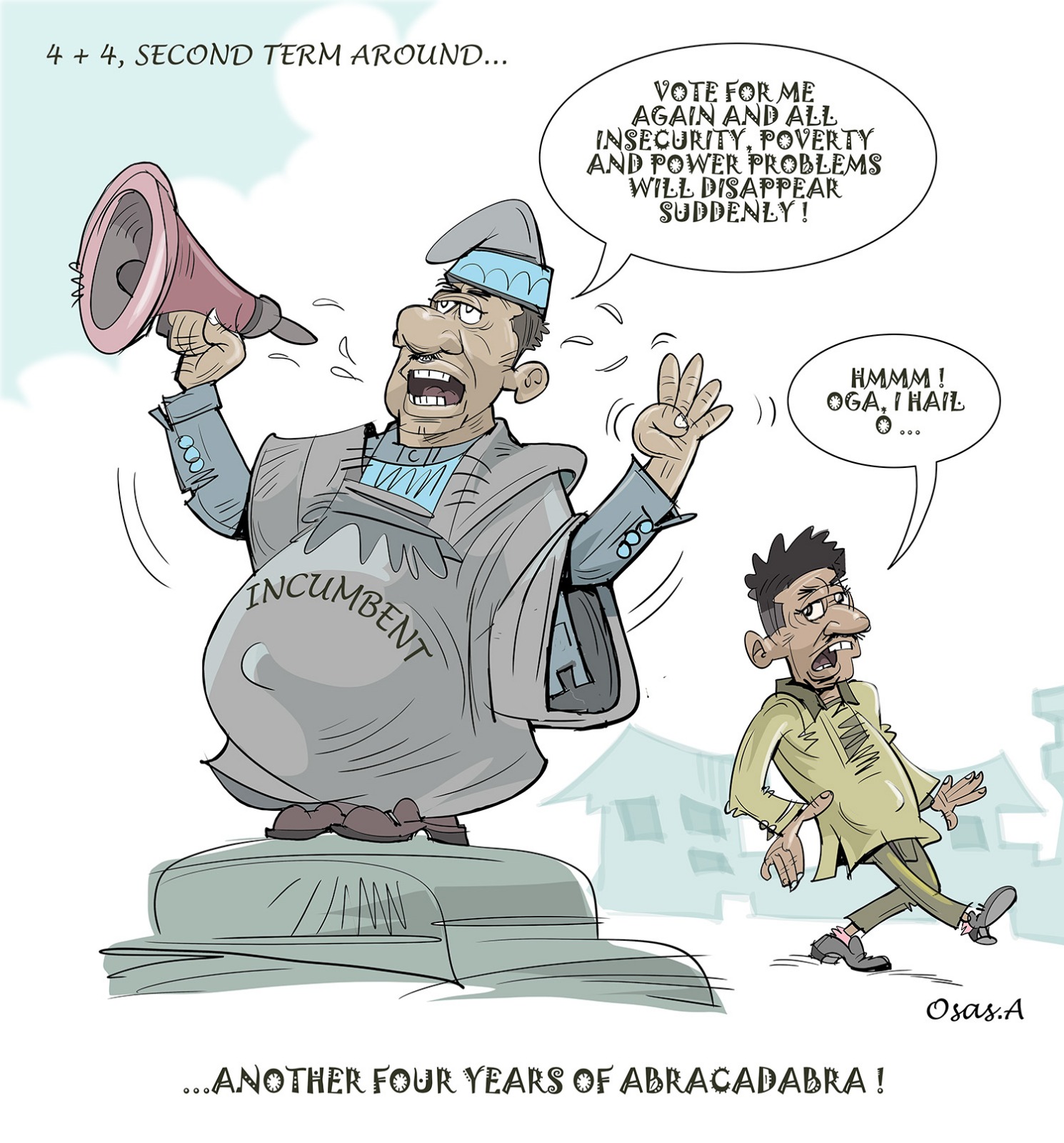

The crisis exposed and deepened fault lines within the ruling and opposition structures in Rivers and beyond. The People’s Democratic Party (PDP) apparatus in the state fractured into factional networks centred on patronage, appointments and control of state institutions — a fragmentation that will complicate candidate selection, local governance and legislative cohesion ahead of future elections. For Wike, who remains a major regional powerbroker, and for Fubara, whose mandate was briefly suspended, the political calculus is now about damage control: repairing legitimacy, retaining patronage bases and convincing voters that governance — rather than personal survival — will be the priority.

Security strategy: short-term gains, long-term needs

Operation-style security deployments can reduce visible theft and attacks, but long-term pipeline security requires comprehensive community engagement, livelihoods programs and transparent local contracting. Nigeria’s broader anti-theft campaigns and naval operations have shown improvements in recent months, but the Rivers crisis highlights that security without meaningful economic alternatives and environmental remediation will only deliver episodic, not sustained, protection.

What must change: policy and institutional lessons

Clearer legal guardrails. The nation needs more precise statutory guidance on when emergency powers are appropriate and what procedural safeguards must accompany them, to avoid perceptions of arbitrary federalism.

Institutional conflict resolution. Parties and states should develop formal mediation and arbitration mechanisms to resolve intra-party disputes before they collapse governance. Neutral elder panels, judiciary-backed mediation and party-embedded ombuds structures can help.

Pipeline governance model. A hybrid model that pairs security with direct community benefits (local employment in protection programs, verified revenue-sharing, environmental clean-up funds and independent monitoring) can reduce incentives for sabotage.

Direct advice to the protagonists (practical and political)

To Nyesom Wike: convert influence into institution-building. Use bargaining power to sponsor transparent reconciliation mechanisms within the PDP and to fund non-partisan development projects that blunt perceptions of vendetta politics. Leaving a legacy of stronger local institutions is more durable than short-term political wins.

To Siminalayi Fubara: prioritise governance credibility. Demonstrable transparency in budgeting, early and visible reconciliation gestures toward the legislature and community outreach programs in oil-affected areas will reduce vulnerabilities to future federal intervention and rebuild legitimacy with voters and institutions.

Both leaders should publicly commit to a time-bound reconciliation roadmap, accept independent monitoring, and depersonalise disputes to permit restoration of normal democratic contestation.

Conclusion — the choices ahead

The lifting of the emergency restores formal democratic order, but it does not erase the causes that prompted federal intervention. Rivers’ future — and, by extension, a significant portion of Nigeria’s oil revenues — depends not only on security operations but on credible, locally anchored governance reforms. If political actors and the federal centre can convert the crisis into a platform for institutional repair and economic inclusion, Nigeria will have turned a dangerous rupture into a rare opportunity for stabilisation. If they do not, the next cycle of confrontation and infrastructure damage may be only a matter of time.

Akingbohungbe—author, reporter, motivational speaker– writes from Ogun State,