With the enactment of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), stakeholders and the public expected a significant positive turnaround in oil and gas management, away from decades of deliberate opacity and corruption. The extant law was designed to instigate reforms that guarantee transparency, competitiveness and less of political interference and manipulation.

So far, that has not happened since the law became operational in 2022. What has happened is that aspects of PIA are implemented to serve the immediate revenue needs of government, like the removal of petrol subsidy. The more sensitive aspects to ensure transparency, building trust across the value chain towards overcoming inefficiencies in the upstream and downstream are randomly modulated. The sector is largely the same way it had been despite the promised reforms. And that’s the reason individuals are now more visible than having institutions quietly to do thing.

NEITI and other rescue efforts

At a time, the major setback in the sector was that Nigeria, once advertised as the sixth-largest oil producing country, had no clear data of its production volume and receipts. There were situations upstream that denied the country the accurate information. There was also no urgency to acquire the technology and mindset necessary to upscale and enhance the operations, because individuals were profiting from the losses.

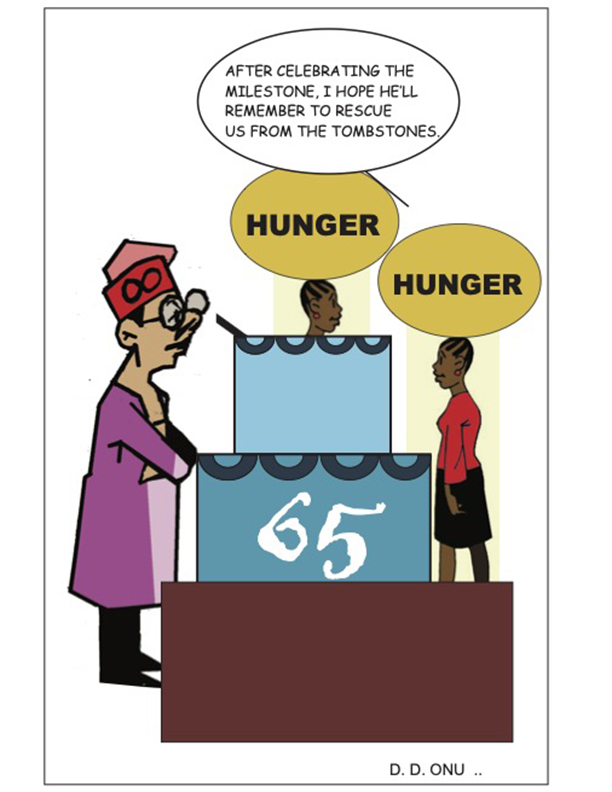

That remained so until President Olusegun Obasanjo’s democratic regime began to seek answers to issues of transparency and accountability in oil revenues. With the encouragement from global Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), the Nigerian Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (NEITI), was formed in 2003/04, to advocate that oil resources must benefit ordinary citizens. That begins with having accurate knowledge of what is produced and sold.

NEITI became an Act in 2007, now having the legal backing to investigate systemic and historic revenue theft and losses. Since then, there has been the campaign for improved governance in oil and gas. The goal is to sustain overall national growth from the extractive sector before the assets are wasted. As of March 2025, NEITI is reported to have facilitated the recovery of $4.85 billion from an outstanding $8.26 billion liabilities. This was from an audit NEITI carried out in 2021. There is a lot more to be recovered. What governments do with what is recovered is another matter.

Despite NEITI and other efforts, crude oil theft and illegal mining have constituted a major drain on the country’s natural resources. In October 2025, Fair Finance Nigeria (FFNG), a coalition of civil society for transparency and sustainable financial practices, reported that 619 million barrels of crude worth $46 billion were stolen between 2009 and 2020. The report blamed weak regulation, systemic corruption and complicity by security operatives for enabling the theft.

Lack of transparency and accountability in the mining sector is reported to cost Nigeria an estimated $9 billion losses yearly, in addition to fueling terrorism across different states. The reported collaboration between state authorities and foreign nationals in illegal mining is an issue the Federal Government must address.

Managing interests and downstream challenges

It is a fact the four public refineries located in Port Harcourt, Warri and Kaduna have lost to refine crude. Before he left office in 2007, President Obasanjo thought it was prudent to sell the refineries. He attempted, but his predecessor, President Umaru Yar’Adua reversed that policy.

Since then, different reports and probes by government suggest that around $25 billion has been wasted in attempts to revamp the refineries. Government is at a loss what to do with the refineries, yet, further delays lead to further depreciation of the assets. Government and NNPCL must make up their mind what they want to do, to ease the tension in the downstream.

Despite being privately owned, the commissioning of the Dangote Refinery (DR), on May 22, 2023, was hailed by stakeholders as the game-changer for the country’s energy sector. It was expected to make Nigeria more energy-secure, with the opportunity to save the foreign exchange that was spent on fuel importation. The country was reported to spend $25 billion yearly on imported refined petroleum products before DR came on stream. Dangote Refinery has said repeatedly that it has the capacity to supply white products that are needed locally and for export.

However, data by the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA), controvert DR’s promised capacity. NMDPRA data released in October 2025, reported a consistent struggle by local refiners, including Dangote, to meet up with their commitment to the local market. The regulator said Dangote Refinery supplied less than half of the petrol it promised to the local market.

The NMDPRA fact Sheet reported that Dangote Refinery averaged around 12 million litres of daily supply between September 2024 and October 2025, instead of the 35 million litres it committed to. The implication is that only Dangote Refinery is supplying the local market, but there is still a shortfall.

According to NMDPRA, whereas there is a shortfall in local refining, PMS consumption had gone up from 47.5 million litres in October 2024 to 56.7 million litres per day in October 2025, resulting in higher prices.

Those figures don’t seem to go down well with DR, whose refining capacity of 650,000 barrels of crude oil per day, the largest in Africa and world’s biggest single-train gets a drubbing with NMDPRA’s statistics. To make matters more annoying for DR, the regulator’s position encourages importation.

In July 2024, when DR was at its most crucial stage of unveiling, NMDPRA said the refinery wasn’t fully completed or licensed. The former boss of the authority, Farouk Ahmed, said then that the refinery was only 45 per cent complete. He equally made unfavourable remarks about the quality of petrol refined at DR.

Two Sundays ago, Alhaji Aliko Dangote went for broke, as he lamented the situation in the downstream sector where he is the major player at the moment. At the press conference, he took on the erstwhile Chief Executive Officer of NMDPRA, Farouk Ahmed, whom he accused of spending taxpayers’ money to fund his children’s costly secondary school education in Switzerland.

Dangote, said: “I’ve actually heard people complain about a regulator who has put his children in a secondary school abroad, which in six years for four children cost about $5 million. You cannot imagine somebody paying $5 million just to educate four children in secondary school. When you look at his income, it does not match this kind of fees….”

“From Sokoto where he comes from, people are struggling to pay N100,000 for school fees. A lot of children are at home, not going to school because of N100,000. I cannot understand why somebody who has worked all his life in government would have four children, whose school fees amount to $5 million.”

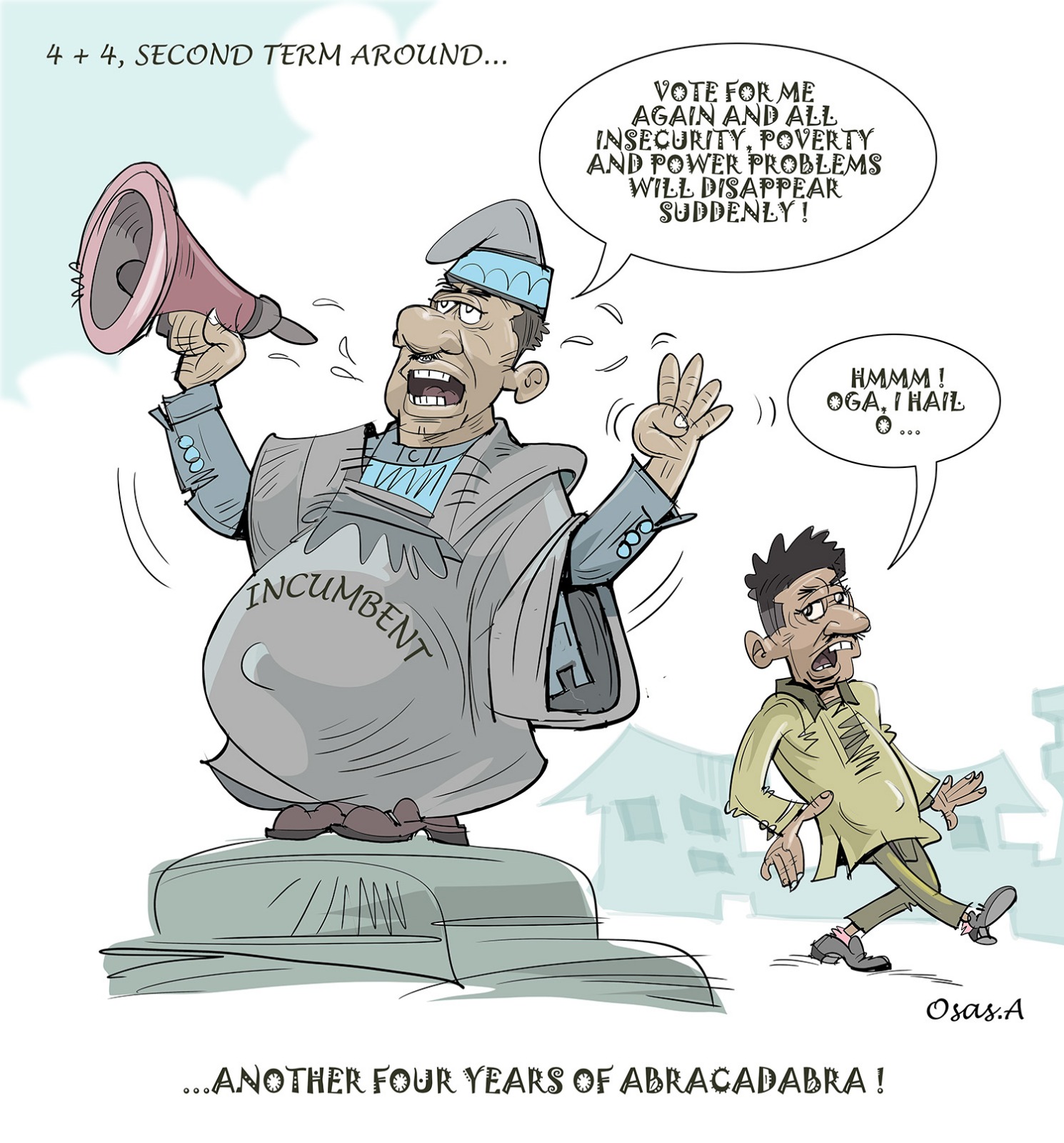

If the PIA were working as intended, a disagreement between the regulator and a stakeholder shouldn’t degenerate into name-calling. But in a country where a major investor had cried himself hoarse, in a persistent bid to call attention to poor governance in oil and gas and no one up there is listening, perhaps doing the advocacy differently might achieve result. And it did, with the resignation of Farouk Ahmed, last week.

However, correcting the ills in the oil and gas sector should not be limited to sacking individuals. The law is very clear on stakeholders’ responsibilities. Let’s stick to it. The ministry that has the supervisory oversight must not wait until matters get out of hand.

There is a place for the regulator and that cannot be discounted. But the regulator must be detached and professional. The minister of Petroleum, President Bola Tinubu, must also declare his interest in oil and gas, and act decisively in that capacity to clear the air on activities, such as acquisitions in the downstream that are suspicious.

There were suspicious protests that indicated certain interests were at play. In May 2025, the National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS), abandoned their studies to wade into oil and gas. They demanded Farouk Ahmed’s resignation over allegations of mismanagement of public funds, job and contract racketeering and abuse of office. In June, NANS later apologised, claiming their allegations were unfounded.

Also in May, a group that called itself Concerned Lawyers and Civil Society in Defence of Public Trust, staged a protest in Abuja, demanding the resignation of Mr. Ahmed, over allegations of abuse of office.

Meanwhile, in July, the House of Representatives Committee on Petroleum, Downstream dismissed petitions demanding sacking of Mr. Farouk Ahmed. Chairman of the Committee, Rep. Ikenga Ugochinyere, said the petitions had no substance.

Crux of the matter

Dangote is worried that entrenched interests are not letting go in a sector that is supposed to be deregulated and devoid of deliberate stumbling blocks. He said: “It is troubling that African countries continue to import refined products despite long-standing calls for value addition and domestic refining. The volume of imports being allowed into the country is unethical and does a disservice to Nigeria.”

The October downstream records showed that Nigerians spent N21.8 trillion on petrol in 12 months, with imported petrol constituting a large chunk of it. Going forward, stakeholders would love to see a more transparent process in how NMDPRA computes its data, so that industry operators would have trust in the system. Other stakeholders, including the media and civil society may be allowed to see back-ends that are not ordinarily available.

It is not enough to substitute personnel at the helm of regulatory authorities. The template that fuels distrust across the value chain is what requires reforming. It is unfortunate that the Senate, clearing house for these matters does not ask relevant questions. They have become loquacious for nothing. All the probes they have engineered into oil and gas and the NDDC have come to naught. At the end of the day, their members go stealthily to NMDPRA, NDDC, NUPRC, FIRS, NNPCL, CBN and other top public outfits to lobby for contracts and jobs for their children. They refuse to carry out selfless oversight work to make PIA work.

Let the political authorities purge themselves of insatiable greed and allow the industry work for national interest.