Established in 1973 to drive Nigeria’s quest for sporting glory, the National Institute for Sports (NIS), Lagos, appeared to have failed to live up to expectations. It has, to date, struggled with the proper identification of its goals and objectives, as well as how to achieve them. This has prompted stakeholders to demand its rejuvenation to meet the country’s needs in sports development, GOWON AKPODONOR reports.

Among several other reasons, sports institutes are meant to equip coaches and sports managers with the necessary tools to effectively produce competitive athletes for the country.

The Australian Institute for Sports (AIS) is a glaring symbol of this endeavour, with the significant role that it has played in the resurgence of the country’s sports since the 1980s, thrusting them up the ladder in global sports.

The United Kingdom Sports Institute has, since 2002 through the last four Olympic and Paralympic cycles, evolved quietly and effectively into an organisation consistently performing at a world-leading level, contributing to over 1,000 British Olympic and Paralympic medals.

There is also the United States’ National Institute for Fitness and Sport (NIFS), which focuses on research, education, and service related to human health, fitness, and athletic performance. It also offers programmes and certifications for various audiences, from individuals seeking fitness and nutrition guidance to professionals in the sports field.

The U.S. sports institute utilises research to create programmes like the “Wellness Companion”, which delivers monthly wellness tips and exercise tutorials for coaches and managers to impact on their athletes.

In Nigeria, the federal government established the Nigeria Institute of Sports (NIS) in 1974, a year after the 1973 National Sports Festival, with the goal of training and retraining the country’s coaches and sports medicine personnel.

The training, among other things, was expected to help the coaches gain the foundational knowledge and practical skills to coach at various levels, from grassroots to professional; have holistic athlete development knowledge by learning to design effective training programmes; understand athlete physiology and foster mental resilience.

It was also designed as an avenue for career versatility for the coaches and managers to have opportunities in sports clubs, schools, fitness centres, national sports federations, and as private coaches.

With various facilities, including training fields and courts, running tracks, sports science centre, a gymnasium, physiotherapy facilities, a sports book library, and hostels, the NIS has all the ingredients required to rival its counterparts in Australia, Great Britain, and the United States in developing champion athletes.

Glory days

In its early years, the NIS met its tasks. Notably, in the build-up to the botched 1976 Montreal Olympics, the NIS served as the first training camp for the country’s athletes before they moved overseas to engage in various trials and competitions leading to the Games.

Nigeria’s preparation for the Montreal Olympics was rated as the best from Independence up to that period before the country led the boycott of the Games in protest against South Africa’s Apartheid regime. The beneficiaries of the NIS training process included Charlton Ehizuelen, who was the world’s best long and triple jumper in the build-up to the Montreal Games, and Bruce Ijirigho, a 400 metres star, who was expected to win a medal in Canada, as well as boxers Davidson Andeh and Obisia Nwankpa.

The NIS also played a major role in Nigeria’s African Cup of Nations victory in 1980, as it also served as the preparatory ground for the Green Eagles ahead of the championship.

The institute also boasts some accomplished athletes and coaches, including Chioma Ajunwa, Nigeria’s first Olympic gold medalist, who is an alumna of the institute, as well as the late Super Eagles manager, Shaibu Amodu.

The school also made the late coach Yemi Tella, who led the Nigeria U-17 football team to a gold medal at the 2007 FIFA U-17 World Cup held in South Korea.

Perennial neglect

OBVIOUSLY, those glory days evaporated long ago as the school, which fell into a bad state from the late 1990s, has remained comatose to date, with most of its hitherto-reverted facilities left to rot by successive governments.

Now, what was meant to serve as a national centre for sporting excellence, providing world-class facilities, coaching, and support services to elite athletes across various disciplines in Nigeria, is a shadow of the dreams of the founding fathers.

Indeed, what was built to be Nigeria’s talent development factory has now become one big event centre, hosting all manner of functions, from book launches to wedding ceremonies and religious activities.

Its gymnasium, which was built to the best global standard in 1974, now serves recreational bodybuilders, who have found better use of the facilities than the owners of the structure.

Some stakeholders hold that one of the ironies of the NIS is that the institute fared better during the military era than with the civilians because most of the managers of the school since the advent of democracy are politicians, some of whom know little or nothing about managing facilities of such magnitude.

According to these stakeholders, previous military governments went to great lengths in seeking out competent administrators/technocrats to run the institute, and not just people with political affiliations to the ruling government.

One of these technocrats was former Secretary General of the Supreme Council for Sports in Africa, the late Dr Awoture Eleyae, who served as NIS’ pioneer principal from 1974 to 1983.

Eleyae was joined in 1976 by three German experts, Hoerst Beyer, Prof H. Dubberke, and Heinze Marotzke, to review the Institute’s curriculum prepared earlier in 1975. These technocrats set the standard for the institute to produce quality athletes and officials for Nigerian sports.

Comparing the NIS to the Australian Institute for Sports, the stakeholders conclude that the Nigerian version has not made a meaningful contribution to the country’s efforts at the Olympic Games, the way the AIS has.

Since 1974 to date, Nigeria has won just three gold medals at the Olympic Games compared to Australia’s 167 gold medals since 1981. Great Britain has won 207 gold medals since 1981, while American athletes have won a total of 2,765 medals (1,105 of them gold) within the same period.

Structural defects

THE NIS’s glaring failure has constantly elicited many questions, prominent among which is: “What is the problem of the NIS?”Responding to this, a former Green Eagles Captain, Segun Odegbami, who was the NIS Board of Trustees chairman between 2003 and 2005, said the problems are many.

“I left the NIS 12 years ago. Our intention then was to model it after the Australian Institute of Sport. But those running the Sports Ministry did not understand the concept and wanted an academic institution to award diplomas that were equivalent to OND and HND.

“Unfortunately, entry qualifications, content of the programme and duration do not meet the standards of those qualifications, and therefore constituted a deviation from the original concept of the institute,” Odegbami said.

According to him, the NIS still struggles to date with proper identification of its goals and objectives, and how to get there. Asked why Nigerian athletes are still being trained by foreign schools, Odegbami said: “The NIS cannot train any athletes considering its entire setup and personnel, and curriculum. That is why Nigerian athletes are not a part of the deliverables from the NIS.”

Odegbami was blunt in describing the NIS as an institute with no value. “The NIS has no value. It does not equate to anything in the government or private sector schemes. At best, it just shows that some level of training has taken place without known substance to its value.”

Additionally, Odegbami feels that the yearly budget of the NIS cannot help the institute achieve any meaningful progress.

“I have no idea of the budget. Almost nil beyond what is used to pay salaries and a little maintenance cost,” he said. For a Los Angeles ’84 Olympics weightlifter, Emmanuel Oshomah, there is a huge disparity in research facilities between the NIS and other foreign sports institutes, particularly the Australian Sports Institute.

“The Sports Institute in Australia is well-equipped with modern facilities, enabling coaches to receive comprehensive training. We don’t have such at the NIS in Lagos.”

Oshomah also said that the NIS has challenges in meeting international standards because of its poor budgetary allocation and policy inconsistency. “Despite the efforts of indigenous lecturers to meet international standards, challenges persist, particularly regarding punctuality and adherence to schedules, which can hinder progress.”

Certificate issued by the NIS, he said, is treated with disdain by athletes, who now prefer to train in foreign institutions. “The preference for foreign training among our athletes may stem from priorities and choices. While the NIS certificate holds recognition in West Africa, athletes may seek broader international recognition and opportunities offered by foreign institutions.”

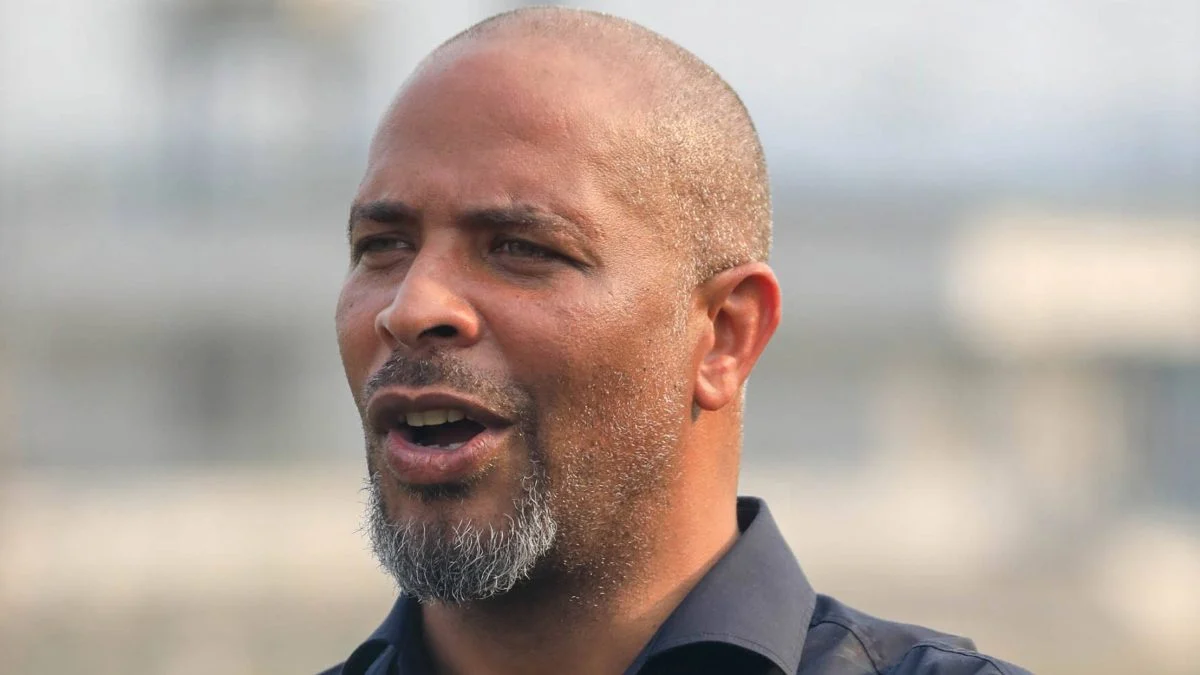

Incumbent Director General of the school, Philip Shaibu, also cited two personal negative experiences with the NIS in a recent interview. Said the former deputy governor of Edo State: “I was one of those Nigerians who felt that nothing was happening at the NIS. One of the negative experiences was when Edo Queens qualified for the CAF Champions League in 2024, and I saw our coach, Moses Aduku, sitting in the stands. I asked why, and he told me he wasn’t allowed on the bench because his NIS certificate wasn’t recognised.”

CAF regulations stipulate that coaches must meet specific licensing requirements to sit on the bench during interclub competitions such as the CAF Champions League or Confederation Cup. Head coaches are required to hold a CAF ‘A’ License or a valid PRO License from a sister confederation (e.g., UEFA, AFC), while assistant coaches must possess a CAF ‘B’ License.

Shaibu described the incident as a wake-up call and a symbol of the broader credibility crisis facing the institute. He likened the NIS to the engine room of Nigeria’s sports ecosystem—one that must be properly serviced to perform at an optimal level.

Tepid efforts to revive institution not enough

SEVERAL efforts to revive the institute died once their initiators left office. Former President Goodluck Jonathan promised to set up a special sports intervention fund to cater to six critical areas to promote training, education, and welfare of retired and performing athletes.

Jonathan wanted to use the fund to strengthen sports institutions, especially the NIS in Lagos and Abuja. The dream died with his administration.

Earlier, the Olusegun Obasanjo administration had attempted to revitalise the NIS through a bilateral relationship with the Australian government between 2001 and 2002, which led to the division of the institute into two arms, i.e. the Education/Research and the Athlete Development Centres.

The Education Centre, located in Lagos, was saddled with the responsibility of ensuring the production of top-quality sports manpower and sports research, while an arm of the institute was created in Abuja for the Athlete Development Programme aimed at discovering, harnessing, and nurturing young, talented athletes into high-performing elite athletes. This plan also died in infancy.

Also desirous of resuscitating the NIS, President Bola Tinubu approved N1.88 billion for it as part of the 300 per cent increase for the sports sector in the 2025 budget.

Tinubu’s “unprecedented” budget of N94.9 billion for sports in 2025 is seen as a bold step to revitalise the sector, as it is a sharp increase from last year’s N31.24 billion.

The sum of N18.59 billion was allocated for the rehabilitation and repair of fixed assets, which include the NIS. Shaibu’s appointment as DG is with a view to resuscitating the comatose school.

“What I saw today is unacceptable. This institution was meant to be a centre of excellence, but it’s now a shadow of itself. That must change immediately,” he said after he toured the facility upon resumption.

Shaibu declared a state of emergency on the institute, saying: “Restoring the NIS is not just about buildings; it is about reviving our sports ecosystem from the grassroots. Coaches, trainers, and athletes deserve a world-class training environment.” He also said that there is an urgent need to rebrand the institute for Nigeria to produce Olympic medallists.

But Dr Theodore Chukwuemeka, a Physical and Health Education expert, said the new move would end like the others before it if certain basic things are not taken care of.

He said: “The new director general and the Federal Government must decide if they want the institute to return to its role as an international athletes’ breeding centre. If that is the case, they must provide the facilities and modernise their architecture to meet the realities of the day.

“The hostels are no longer fit for purpose. For elite athletes to live and train there, befitting accommodation must be provided for them, else no top athlete will want to stay in the NIS in its current situation.

“The curriculum must be reviewed to address current realities, while qualified and experienced teachers must be recruited to fill the academic needs of the institute. If we do not do these things, it means that we are still politicking with the institute. The DG will express outrage, grab headlines, and when he’s done his bit, there’ll be no comparison of before and after. It’s the routine.”