Dr. Olufela Oridota, a Consultant Public Health Physician/Epidemiologist at Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), in this interview with GERALDINE AKUTU, enlightens on Viral Hemorrhagic fevers (VHF), causes, treatment and management.

What are Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers?

These are disease conditions caused by many unique families of viruses namely: Arenaviridae, Bunyaviridae, Filoviridae and Flaviviridae. They cause diseases often referred to as emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. They are named hemorrhagic fevers because of their unique ability to cause high fever and haematological disorders at the late stage of the diseases. The viruses share common characteristics such as: They are enveloped RNA viruses, their natural reservoirs are largely animals (zoonosis), humans are mainly their accidental host, and they cause epidemic prone diseases. Lassa fever belongs to the Arenaviridae, Rift valley fever (RVF), Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) and Hantaviruses belong to the Bunyaviridae, Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Marburg belongs to the Filoviridae, while Yellow fever and Dengue fever belong to the Flaviviridae.

These diseases are widely distributed in the tropics and sub-tropics. Ebola, Marburg and Lassa fever occur in some parts of the sub-Saharan Africa. CCHF is seen in the steppe regions of the central Asia, central Europe and Southern Africa. RVF is seen in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Lassa fever virus was first isolated in 1969, following an outbreak in Lassa town in Borno State, North-East Nigeria, involving missionary nurses. Outbreaks have continued to be reported in Nigeria and other West African countries since then. Ebola virus was first isolated in 1976, following an outbreak in the DRC Congo and derived its name from Ebola River, which borders South Sudan and DRC Congo. Outbreaks have continued to be reported in that region and recently in the West African region between 2014 and 2016.

How are they transmitted?

Viruses causing hemorrhagic fevers are transmitted by various vectors and rodents, as well as through human-to-human or animal to human contact. Mosquitoes transmit yellow fever, dengue and RVF. Rodents transmit Lassa fever and Hanta virus. Ticks transmit CCHF, while bats are thought to transmit Ebola and Marburg. Also in Ebola and Marburg, transmission occurs from contact with body fluids of primates, other mammals and infected humans. In Ebola, virus has been isolated from semen and eye fluid months following recovery.

However, transmission through this route is yet to be documented.

Furthermore, in CCHF, transmission can occur from direct contact with blood or tissues of infected farm animals or humans. RVF can also be transmitted through direct contact with blood of infected animal or through consumption of unpasteurised milk. Lassa fever is transmitted via infected rats, when humans consume food or water contaminated with the urine or faeces of such rats. Human-to-human transmission also occurs through direct contact with blood or body fluids of infected persons. Infection with hemorrhagic fevers can be amplified in hospital settings as a result of poor infection prevention and control.

What are the signs and symptoms?

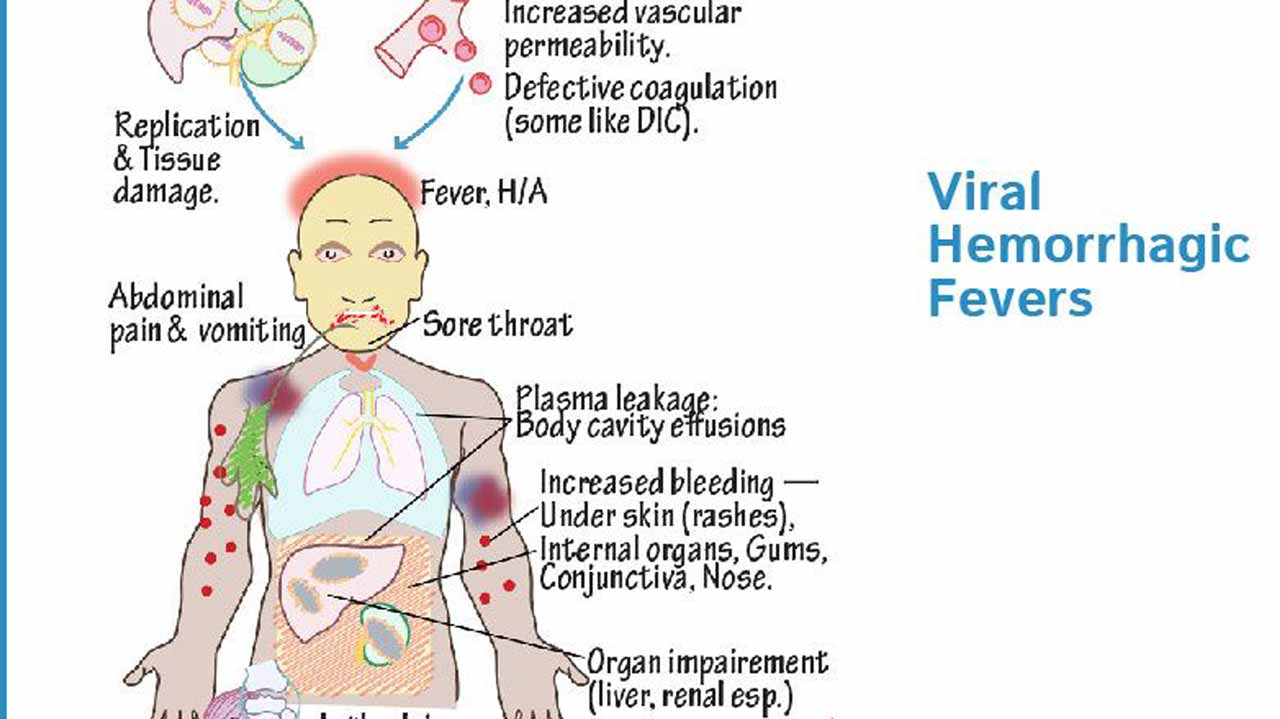

Their signs and symptoms are similar, with slight variation. All of them present in their early stage with non-specific symptoms, such as fever, malaise, body and joint pains. Almost in all of them, the late stage is characterised by haematological disorders.

In Lassa fever, symptoms begin to manifest after six to 21 days incubation period, following exposure. Early symptoms include fever, malaise and muscle aches. It may be followed by pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, tonsillitis, headache, chest and/or epigastric pain and cough, among others. The late stage is accompanied with bleeding from orifices, shock, renal failure and death. However, not all infection leads to clinically severe disease.

In yellow fever, incubation period is between three to six days, following exposure. The early symptoms include fever, headache, generalised body pains, abdominal pains, nausea and vomiting and generalised body weakness. In the late stage, there is jaundice, bleeding disorders and renal failure. In some cases, there may be unapparent or mild infection.

In Ebola virus disease, early symptoms present after three to 21 days, following exposure. They include fever, headache, sore throat, muscle aches and generalised body weakness. They may be followed by diarrhoea, vomiting and epigastric pain. The late stage is accompanied with both external and internal bleeding, shock, renal failure and death.

How are they diagnosed?

Diagnosis is through isolation of virus in the blood and body fluids of an infected person. Also, it can be made through various serological tests.

What is the treatment?

It is only Lassa fever that has as an approved drug for treatment namely, Ribavirin. This drug, when initiated early in the disease, can cure Lassa fever. However, when initiated late in the disease, it may be of little help. In EVD, some trial drugs have demonstrated high efficacy in patients, when initiated early. However, none has been approved for general use. In all hemorrhagic fevers, supportive treatment is usually given and patients generally do well with early presentation.

Can they be prevented and controlled?

There is a vaccine for Yellow fever, which is currently known to confer life immunity when taken. Some trial vaccines for EVD have demonstrated high efficacy. However, none has been approved for general use.

All viral hemorrhagic fevers are notifiable diseases under International Health Regulations and the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response. A case of any VHF is considered an outbreak. A sensitive surveillance system is required to prevent large outbreaks.

Control of VHFs is mainly through breaking the chain of transmission. In Lassa fever, behavioural change communication is developed, targeting behaviours that fuel transmission in the endemic communities. It includes discouraging bush burning and open drying of food materials, promoting proper food storage and preparation and rodent control measures.

For mosquito borne infections, integrated vector management is an important strategy for their control.

Also, wearing of protective wears may be helpful for those whose trade involve visiting the forest. In transmissions that occur in livestock farming and processing, ensuring adequate personal protective wears are worn, while interacting with livestock or their products may reduce the risk of transmission. In all VHFs, hospital transmissions can amplify outbreaks. Therefore, strict infection prevention and control protocols can limit human-to- human transmission within hospital settings.

For control at the points of entry, many countries require evidence of vaccination for Yellow fever before embarking on international travel into their countries. This is the so-called yellow card. No other VHF requires evidence of vaccination for international travel.

Also, in active outbreaks in any country, thermal scanners or thermometers are used in screening inbound and outbound passengers at the points of entry for fever, the commonest symptom of VHF.

What is the role of Epidemiologists in hemorrhagic fever control?

Epidemiologists in the academia are involved in the control of hemorrhagic fevers in many ways. Firstly, they are involved in the capacity building of the different cadres of health workers on surveillance (detection) and response to outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever. They are also involved in research to understand further the epidemiology of hemorrhagic fever, which can aid their control. They are also involved in advocacy, especially in strengthening infection prevention and control protocol in the hospital settings.