Music has often been described as food for the soul and I bet you would not put up a fight to that because many a song jolts people into nostalgia and other kinds of feelings. Not solely for the feeling but for the secrets these feelings hold. Music also means different things to different people by playing a role in society as being vital to peoples’ experience and primal to human culture.

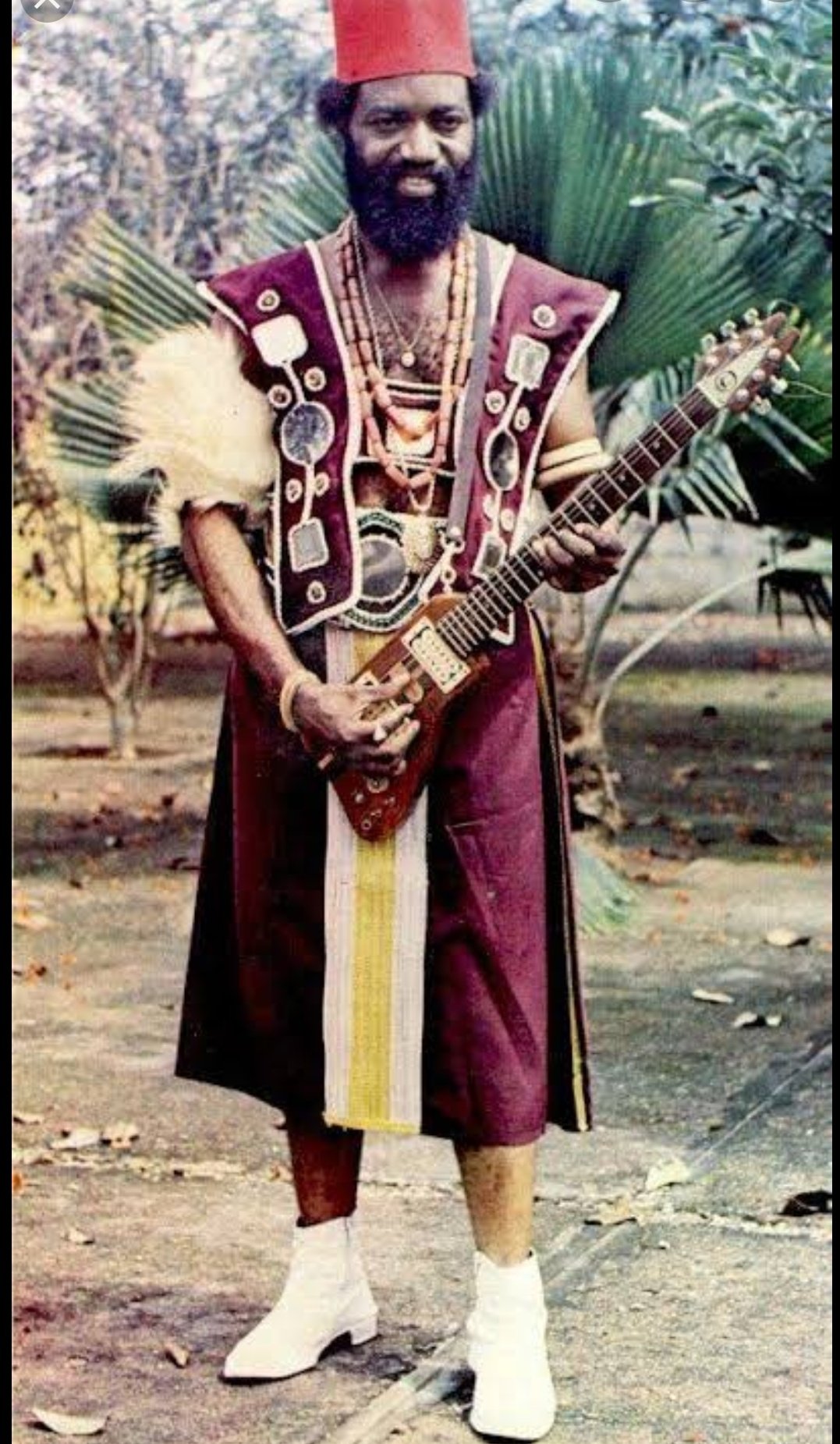

The stringing of the guitar in crescendo with the drums and the grand entrance of the trumpet are the popular sounds of highlife music. In the Igbo community, these sounds have been made popular by the likes of Oliver De Coque and Osita Osadebe among others. Through their talent in music, these minstrels used their genre of highlife music to highlight and expand the worldview of the Igbo society. Richly embedded in the traditions of the Igbo people, their songs have been known not only to inform culture, but also to divulge secrets or precepts to life, constantly dishing out advice and commentaries on life’s issues while being a praise singer to the Igbo society home and in the diaspora.

[ad]

With the invasion of pop music and other aspiring genres of music, the songs of the old like that of Osadebe and Oliver De Coque holds strong in quality and content, offering a greater deal to society of the past and still in the present. These highlife legends were gifted. Guitarist Olive De Coque learnt the mastery of this instrument from a Congolese at a young age, while Osadebe picked his mastery up for his time with the Empire Rhythm Orchestra.

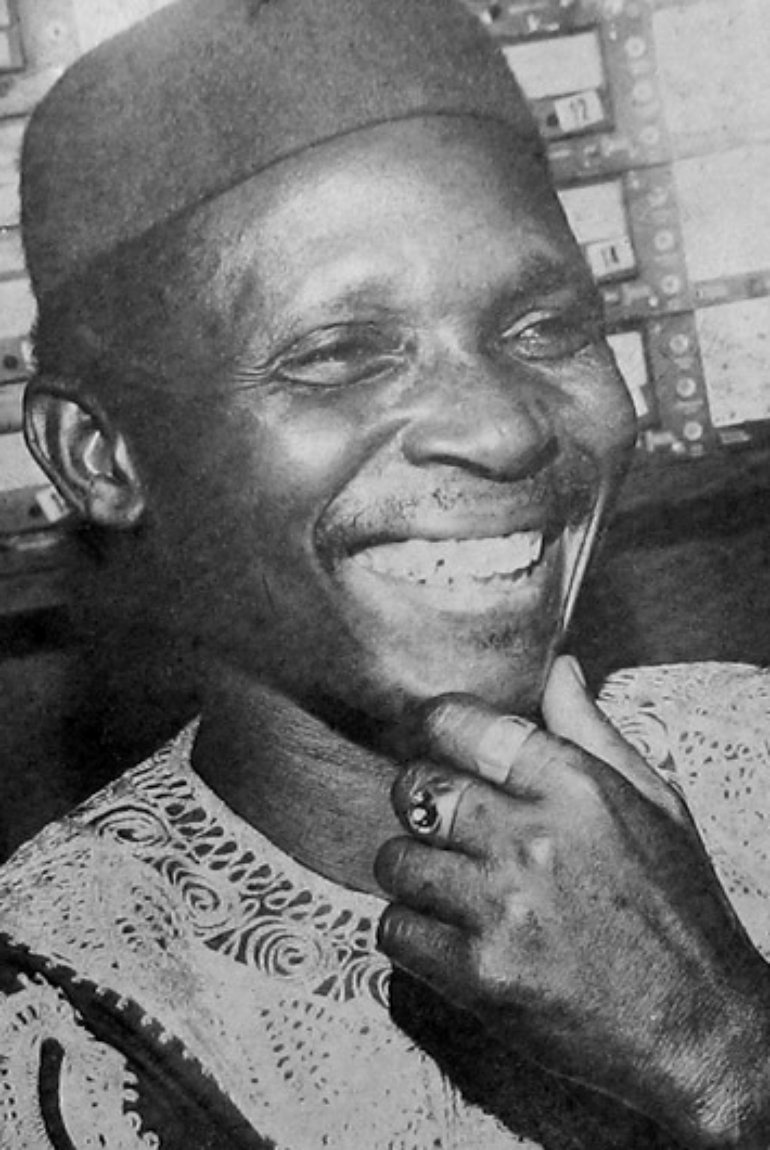

In tune with this, he is known as the Doctor of hypertension because of his musical ability to cajole one with his slow rhythmic vibes; a mellow meditative tempo. This is capped with his Afro Cuban accented bass and percussion borrowing from the Rockers lead lines on electric guitar. With his feel-good music, Osadebe lulls the audience as he dreamily muses, coos, sighs, uses adages, words of wisdom and inspiration. With this, he started the “oyolima” style we know today; a state of tranquillity, relaxation and pleasure.

Long before the 21st-century term “Igbo Amaka” – a phrase that speaks of the appreciation of the Igbo heritage, the Osondi Owendi crooner and his counterparts have since preached these in their songs, always clamouring for unification and community growth of the Igbo people through upliftment and appraisal of the achievements of notable Igbo men and women.

Like the Nigerian artist who follows the steps of social critic, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, the king of Afrobeat who satirically used his songs to radically evokes change politically, and is an emblem to such ideal, this same act with a twist is deployed by Osadebe and Oliver De Coque to nurture better Igbo people and society.

Osadebe, more often than not, chanted in his songs about life and how to navigate in an ever-changing world. Using his songs, he provided a road map to life by unequivocally saying “live in the moment”. An instance is his pioneer with “Peoples Club Odogwu” of 1977.

These feel-good songs of these minstrels do more than just sounds and words but mirror the cultural identity, aspirations, philosophy, history, social and economic system of the eastern part of Nigeria; forming a world view and exposing the rich cultural tradition.

The multiplicity of the function of music cannot be overemphasised having a full impact on people’s feelings and interpretation of events. So the hype, quality and appreciation of their songs are on the premise of cultural principles fused with the instructional properties of the music which therefore serves the dulce et utile. This applies to other non-Igbo societies. Music poses as historical documentation of a particular time in the world and society and these Igbo entertainers through their lyrics envelope it all showcasing through their talents, idioms and philosophical views to life.

[ad unit=2]