Nigeria on Sunday, October 20, 2019, marked five years since the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the country Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) -free.

The WHO, on October 20, 2014, officially declared Nigeria Ebola-free, having passed the mandatory period with no new cases; 42 days after the last confirmed case of the virus was discharged from the hospital, giving sufficient confidence to declare the outbreak over.

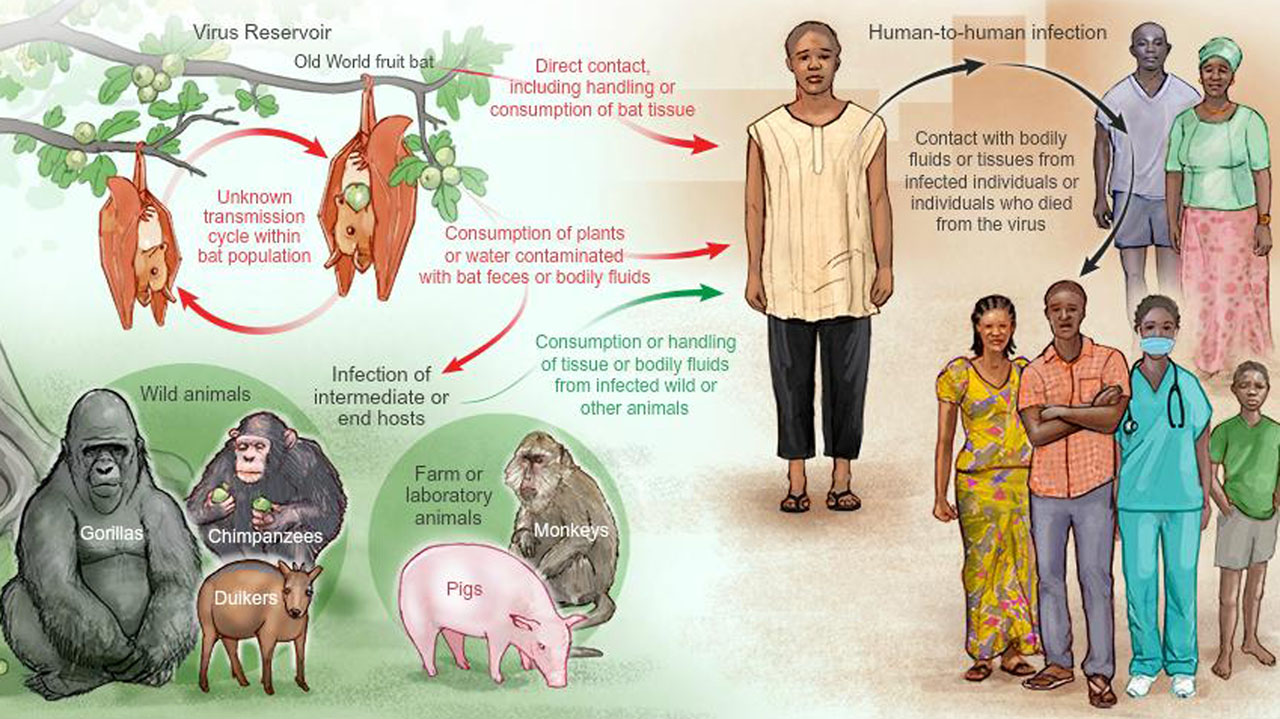

But five years on, the threat still persists. Why? Scientists have warned that deadly diseases such as Ebola, monkeypox, Lassa fever, Yellow fever that have fruit bats, monkeys, mosquitoes, rats as animal hosts may crop up in countries not used to the killer viruses because global warming is pushing disease-ridden vectors inland.

The scientists said zoonotic diseases – illnesses that spread between animals and humans – are becoming the “new normal.”

They said more than two-thirds of all infectious diseases originate in animals including Ebola, Lassa fever, monkeypox and West Nile virus. These diseases contribute to the global health and economic burden that disproportionately affects poor communities.

The experts in a study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications said several countries that have never experienced Ebola, including Nigeria, which is home to 191million people, Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda are particularly at risk.

The researchers suggested that in West and Central Africa, where outbreaks have traditionally clustered, outbreaks would happen more frequently and spread farther, via airlines, to previously unaffected areas within the next 50 years.

Using the current network of airline flights in their model, the study suggests that there is a high risk of Ebola spreading to China, Russia, India, Europe, and the United States.

The experts said in the worst-case warming scenarios that they looked at, the area that could be affected by “spillovers” of Ebola – when the virus jumps from an animal to a human – will increase by nearly 15 per cent compared with today.

The study found that the climate crisis would bring a 1.75 to 3.2-fold increase in the rate at which the deadly virus spills over from animals to humans by 2070.

Meanwhile, the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) on Wednesday confirmed five news cases of Monkeypox in Lagos, Rivers and Akwa Ibom states. The resurgence comes two years after the index case was reported in the country. While Lagos, in the current reappearance, recorded three cases, Rivers and Akwa Ibom have one each.

Also, the Lassa fever outbreak in Nigeria that hitherto used to be a seasonal affair has persisted for two years now with the country recording new cases and deaths on a monthly basis.

Latest figures from the NCDC showed that in the reporting week 41 (October 7 to 13, 2019) five new confirmed Lassa Fever (LF) cases were reported from Edo (two), Ondo (two) and Bauchi (one) states with no new death. From January 1 to October 13, 2019, a total of 4099 suspected cases have been reported from 23 states. Of these, 726 were confirmed positive, 19 probable and 3354 negatives (not a case). Since the onset of the 2019 outbreak, there have been 154 deaths in confirmed cases. Case fatality ratio in confirmed cases is 21.2 per cent.

Also, Yellow fever is another viral infection with an animal host (Aedes aegypti mosquito) that has persisted in the Nigerian environment.

However, the NCDC has insisted that Nigeria is better prepared for another Ebola outbreak today than the country was in 2014.

Meanwhile, the researchers said there will be an increased risk of more devastating outbreaks in areas of Africa that have not seen outbreaks before under all of the climate warming scenarios they looked at, including if humans cut their carbon emissions significantly or only slightly. Higher temperatures and slower social and economic development would lead to greater risk.

The findings showed how environmental destruction caused by climate change and deforestation could lead to a greater spread of deadly human diseases via animals and other organisms, with serious consequences for public health.

The latest findings could help governments decide where to target potential drugs or boost healthcare infrastructure.

However, a statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on October 18, 2019, urged all countries:

*No country should close its borders or place any restrictions on travel and trade. Such measures are usually implemented out of fear and have no basis in science. They push the movement of people and goods to informal border crossings that are not monitored, thus increasing the chances of the spread of disease. Most critically, these restrictions can also compromise local economies and negatively affect response operations from a security and logistics perspective.

*National authorities should work with airlines and other transport and tourism industries to ensure that they do not exceed WHO’s advice on international traffic.

*The Committee does not consider entry screening at airports or other ports of entry outside the region to be necessary.

The Committee emphasized the importance of continued support by WHO and other national and international partners towards the effective implementation and monitoring of these recommendations.

Also, the WHO has welcomed the European Medicines Agency (EMA) announcement recommending conditional marketing authorization for the rVSV-ZEBOV-GP vaccine, which has been shown to be effective in protecting people from the Ebola virus.

The announcement by EMA, the European agency responsible for the scientific evaluation of medicines developed by pharmaceutical companies, is a key step before the European Commission decision on licensing. In parallel, WHO will move towards the prequalification of the vaccine.

In the past five years, WHO has convened experts to review the evidence on various Ebola vaccine candidates, informed policy recommendations, and mobilized a multilateral coalition to accelerate clinical evaluations. The EMA review was unique in that WHO and African regulators actively participated through an innovative cooperative arrangement put in place by WHO, which will help accelerate registration for the countries most at risk.

A randomized trial for the vaccine began during the West Africa Ebola outbreak in 2015. When no other organization was positioned to run a trial in Guinea during the complex emergency, the government of Guinea and WHO took the unusual step to lead the trial.

A global coalition of funders and researchers provided the critical support required. Funders included the Canadian Government (through the Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, International Development Research Centre, Global Affairs Canada); the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (through the Research Council of Norway’s GLOBVAC programme); the Wellcome Trust; the UK government through the Department for International Development; and Médecins Sans Frontières.

The trial was successfully run using an innovative ring vaccination design. In the 1970s, this ring strategy helped to eradicate smallpox, but this was the first time that an experimental vaccine was evaluated this way.

There are eight vaccines undergoing clinical evaluation. WHO continues to work with partners towards an internationally coordinated governing mechanism to ensure access according to risk criteria, and manage supply and stockpiles, especially as supply will remain limited until a full manufacturing capacity is established or other vaccines are licensed.

A roadmap aiming to accelerate prequalification and coordinate actions and contributions to the licensing and roll-out of the rVSV-ZEBOV-GP vaccine in African countries has been developed.

In the current Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, more than 236,000 people have been vaccinated with rVSV ZEBOV GP donated by Merck to WHO, including more than 60,000 health and frontline workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in Uganda, South Sudan, Rwanda, and Burundi.

The 2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa killed more than 11,000 people directly, and knock-on effects, such as diverting medical resources away from other conditions, caused thousands of more deaths.

The incurable virus, which has a deadly 90 per cent fatality rate, has so far largely been contained to the Congo, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea.

According to a prediction by researchers, neighbouring countries may have to brace for an onslaught, which will put the lives of millions at risk. They said the number of Ebola cases is set to soar under any type of climate change.

The prediction is based on mathematical models that took into account a range of factors, including human contact with the wild animals that spread it. Besides bats, other wild animals sometimes infected with Ebola include several monkey species, chimpanzees, gorillas, baboons, and duikers.

Lead author of the study, Dr. David Redding, an environmental geneticist at University College London, said: “It is vital we understand the complexities causing animal-borne diseases to spillover into humans, to accurately predict outbreaks and help save lives.

“In our models, we have included more information about the animals that carry Ebola and, by doing so, we can better account for how changes in climate, land use or human societies can affect human health.”

The Ebola virus is mainly associated with fruit bats in West and Central Africa. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is currently grappling with the world’s second-largest Ebola epidemic on record.

According to the latest figures from the World Health Organisation (WHO), it has claimed more than 2,000 lives, with 3,000 confirmed infections since the outbreak was declared on August 1, 2018.

Redding’s computer programme tracks how changes to ecosystems and societies combine to affect the spread of infectious disease.

By combining the impact of climate, land use and human population factors; it came up with the ones that have previously occurred even with no case data – demonstrating the high level of accuracy.

It also found future outbreaks are 1.6 times more likely in scenarios with increased warming and slower socioeconomic development.

Previous Ebola outbreaks affected relatively small numbers of people. The WHO has said countries and other bodies need to focus on preparing for new deadly epidemics.

Ebola is a virus that initially causes sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain, and a sore throat. It progresses to vomiting, diarrhea and both internal and external bleeding.

People are infected when they have direct contact through broken skin, or the mouth and nose, with the blood, vomit, feces or bodily fluids of someone with Ebola. Patients tend to die from dehydration and multiple organ failure.

The WHO says climate change, emerging diseases, exploitation of the rainforest, large and highly mobile populations, weak governments and conflict are making outbreaks more likely to occur and more likely to swell in size once they did.

Global warming is not the only environmental change that could increase disease risk. Clearance of the Amazon rainforest seems to be driving up the spread of malaria, suggests research by Andrew MacDonald and Erin Mordecai at Stanford University in California, US.

Their analysis of 13 years of malaria cases and forest satellite data for the Brazilian Amazon show that a 10 per cent increase in deforestation was associated with a 3.27 per cent increase in malaria cases – almost 10,000 additional cases every year. That is probably because more people end up settling closer to mosquito-infested areas and are more likely to get bitten, while logging creates more mosquito-friendly habitats.

The relationship also seems to hold in reverse – as malaria rises, economic activity, and hence deforestation slows. Nonetheless, MacDonald says that counter-effect will never halt deforestation and the world needs to pay attention to greater disease risk from environmental damage.

In addition to the spread of Ebola, scientists predict higher temperatures will bring more cases of malaria, diarrhea, heat stress, heart defects, malnutrition, and antibiotic-resistant diseases.

Ultimately, scientists believe the climate crisis could “halt and reverse” progress made in human health over the past century. The WHO predicts that rising global temperatures could lead to many more deaths than the 250,000 deaths a year.