Across a decade of grit, dance revolutions, street bangers, and cultural resets, Zlatan Ibile has evolved from a campus underdog into one of Afrobeats’ loudest symbols of survival and reinvention. With his new album Symbol of Hope, the rapper revisits his scars, his triumphs, and the legacy he’s determined to build for the streets.

11 years ago, a young Zlatan Ibile waltzed into a talent show organised on his campus at the Moshood Abiola Polytechnic, in Ogun state, with wide-eyed ambition and raw street energy. Having nearly missed the auditions due to a mix of imposter syndrome and anxiety, he eventually climbed the stage, performed a freestyle dance move and thrilled the audience with his raps. By the end of the audition, he emerged the winner of the 2014 Airtel One Mic talent show, besting 140 other candidates to clinch the grand prize of a saloon car.

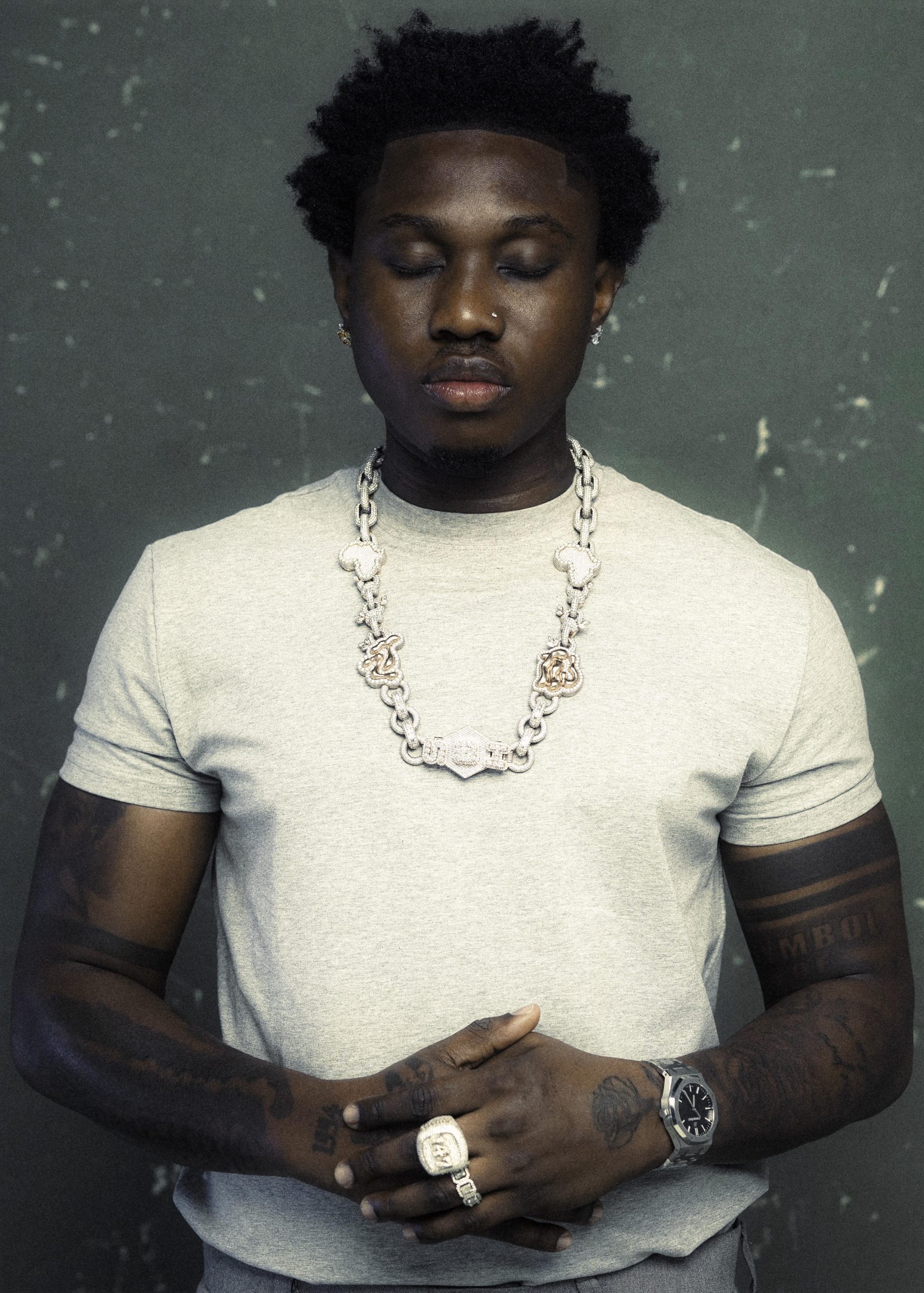

Born Temidayo Israel, Zlatan Ibile rose from the streets of Lagos and Ogun states with an unmistakable street hop artistry, distinguished by his sweltering flows and storytelling skill. His earlier ambitions of becoming a professional footballer gave way to music after winning the talent show, unlocking a trajectory that propelled him from campus champion to superstardom within a decade.

Following his 2017 career-sprinting duet with Olamide, My Body, and a slew of other notable singles, such as 2018’s Able God, Zlatan’s opus came in 2019 with his debut album, Zanku. The 17-track project introduced him to a wider fanbase with street favourites like Gbeku (with Burna Boy), Yeye Boyfriend, and the culture-shaping title track, “Zanku,” a contraction of his popular street slogan, ‘Zlatan Abeg No Kill Us.’ The song introduced a legacy dance style — legwork — into Nigeria’s pop culture. Shortly after, he recorded Killing Dem with Burna Boy, off the African Giant album, further cementing his cultural relevance as a street dance/rap maverick in today’s Afrobeats scene.

After his 2021 sophomore album, Resan, and 2023’s follow-up extended play, Omo Ologo, the 30-year-old rapper, label boss and creative mogul returns with his third album, Symbol of Hope, a 15-track melodic rap spin that tributes his earlier street struggles and documents his longevity as a superstar.

Symbol of Hope arrives with the urgency of evolution, a clear marker of growth in Zlatan’s personal and professional life, including fatherhood, which came in 2020, his record label Zanku Records, and his fashion store Zero To The World (ZTTW), which has blossomed from an online pop-up store in 2017 to a full-scale bespoke streetwear brand. Beyond these, it also reverberates as an ode to every hustler out there, longing for hope to persevere in their pursuits of happiness.

Cosied up in his private music studio in Lagos’ highbrow Lekki axis, we sit down with the father-of-one and rap juggernaut, to discuss his come-up journey, his cultural starpower from Zanku/Gbeku dance era to worldwide smash hits, the muse behind Symbol of Hope, and several lores that colour his art.

What does your album title, Symbol of Hope, represent?

It means a lot. The album itself is a symbol of hope — that I can evolve and do better in life. From my last album, Resan, till now, the music shows growth.

Where I come from, things are not easy at all. Some people can’t even feed three times a day. Growing up, I didn’t see luxury cars like Range Rovers or G-Wagons. Most people were just average earners. So, when I make music, I make it for everybody. I want people to sing my lyrics like affirmations: “my life go better.” Even though my life has improved, I still want more. Someone below me wants to be like me. Someone above me still wants better. That’s the spirit behind the album.

You’ve been vulnerable about mental wellness issues like anxiety. How did that surface on this album?

I tweeted once that if your family member wants to do music, you should also keep money for therapy. Not necessarily a professional — your mum, dad, or partner can be therapy. But what people don’t know is, sometimes, your therapist might be your partner or mum. There were times I was having anxiety because my music was blowing up. I didn’t realise that being relevant is a bigger hurdle than the blow-up.

When Olamide gave me my first verse, everything changed. After my first hit, I even told myself I wouldn’t get a tattoo until I had one. When the song dropped, I tattooed “Timileyin” — my name — because my sorrow turned to joy. But staying relevant is harder than blowing. People doubted me. Some said street artists only get one hit. That pressure led to anxiety, panic attacks, overworking, and drinking to stay sane. But despite all that, I kept on going smoothly, from Able God to Killing Dem, to winning awards for Best Rapper and Best Collaboration; it felt special. Everyone wanted a spice of Zlatan in their stew. The Zlatan effect.

At that time, I had no proper structure. No label signed me. It was just me, Olamide, and then Davido supporting me. Then, Davido called me and paid for my music video for My Body (with Olamide). It was my first professional music video. I also recorded Killing Dem at that time. Everything was happening fast. In 2020, I started my record label and decided not to sign anyone immediately. I dropped an EP, and it featured my guys Jamo Pyper, Papi Snoop and the rest. In the midst of everything, I took a break, and people tweeted things like, “Zlatan’s time is over,” even though it was just a three-month break. I was worried, sometimes. Then we made Cash App, and the song blew up, and things balanced again. Over time, I learned to calm down, work hard, record, and focus on what matters, which is to make good music.

Speaking of recording, what is the meaning behind your catch phrase, Kapaichumaruchupako?

(Laughs) Only people from Casablanca de Katamatofia would understand.

Jokes aside, it was another slang that ultimately defined your breakout moment, ‘Zanku’. What does that mean?

It means ‘Zlatan Abeg No Kill Us’. In the second verse, the line came ‘Lamba ti poju/ Zlatan abeg no kill us.” And it stuck from there. People kept using it in comments on social media.

On Zanku itself, before music, I had known dance steps like Alanta, Skelewu, Azonto and all. In my head, I always wanted to have a dance step I was known for, like Lil Kesh had Shoki and Davido had Skelewu. Interestingly, I created a dance when I was in school, it was for my song called Kuzu. It went viral then.

You know, most of these dance styles start from the streets; if you go to Fela’s Shrine, I can bet you that they are already dancing new steps that you might only get to see next year when they go viral. So, that was how I got the inspiration to create the dance step for Kuzu. In fact, the Kuzu dance step eventually became Olamide’s Shakiti Bobo dance. I was surprised, because I was still in school at that time — I hadn’t blown up yet — and the Kuzu dance was already popular in school. So, when I saw it in Olamide’s video, everyone in class was asking me if I sold the dance step. They didn’t know how music works. I saw it as a big inspiration. It didn’t make sense to drag anything with Olamide. I told my friends to forget about the ordeal. I went to post the Shakiti Bobo song because I understood that, before I had gotten popular with Kuzu, other people had been dancing it elsewhere and migrating the dance step with another name.

So, when the legwork dance blew up with the song Zanku, I made sure to protect the name. A lot of people didn’t even know what the Zanku acronym stood for; I let it sink in as a dance step first. When Zanku legwork blew up, a lot of people across the world danced to it, from Beyoncé. It was everywhere. It was the same thing with the ‘Gbeku’ legwork dance. Till today, no other dance step has achieved the same momentum with both dances in Nigeria.

You are popular for cosigning several artistes into fame. What do you look out for in an artiste you’d like to help?

[On] my journey, it’s always been one person or the other helping me; from one person taking me to the studio, to another person buying the SIM card of the form for the Airtel competition. Some people prefer to focus on themselves after they blow up, but not me. People helped me. So I am always down for collaborations. You can’t do everything on your own. As long as you’re doing something nice, I don’t mind. Let’s link up in the studio.

You also dabbled in fashion. Why that move?

Clothes showed me shege growing up. Even after I won my car, I had only one shirt. One lecturer even embarrassed me in class because of it. I couldn’t feed myself. At some point, I had to use the car as a taxi, shuttling Abeokuta to Shagamu at night. I charged like N200 per trip. Some people even tried dodging payment, because they said I won the car. Eventually, I sold the car. And I am grateful to God that it was not the last car I ever had. I can’t even count the number of cars I have bought for people.

What would you say is the biggest lesson fatherhood has taught you?

It made me sit up more. I was 25 when I had my first child. My guys and I were still crazy at that time. As soon as my son came, it toned down the whole madness. I started becoming calm. I started feeling reluctant to do some crazy stuff that I used to do. I wanted my son to look up to me.

Would you encourage him to pursue music if he wanted to?

I didn’t do what my father wanted me to do. I did what I wanted to do. Right now, today, he could say he wants to be an astronaut, and tomorrow he’d say he wants to be an engineer. I feel he is still too young to know what he wants to do. I would love him to play football if I had the choice.

What’s one thing your fans would be shocked to know about you?

I’ve hardly said this anywhere, but I actually stopped smoking four years ago. Even when I make a video with my friends and they happen to be smoking, some fans suspect I do. But the thing is, I’ve quit it and I haven’t gone back to it.

If you weren’t making music, what would you be doing now?

Right now, I’d probably be thinking of ways of making more money.

What would you say is the vision for Zlatan Ibile?

I just want to keep inspiring people: make money, don’t give up, keep pushing. I’ll still drop party jams, but I know some people need the motivation. I’m not where I want to be yet, but I’m grateful for where God has brought me. I make music now with peace of mind, no pressure.