It is wedding season in the Comoros, when the diaspora returns to the tiny Indian Ocean islands for days-long celebrations that mark an essential rite of passage, the “Grand Mariage”.

The elaborate, tradition-infused ceremonies — which can be held years after an initial religious wedding — are most often held in July and August, coinciding with the summer holidays in France which has a significant community of Comoran migrants.

On a recent day in July, Badjanani Square in central Moroni — the capital of the mainly Muslim nation off east Africa — was packed with hundreds of people attending a prayer ceremony ahead of the “Grand Mariage” (French for “Big Wedding”) of a couple based in the central French city of Le Mans.

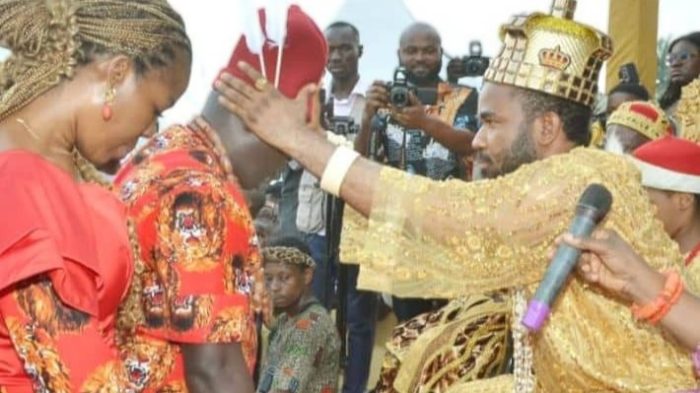

The groom, 55-year-old Issa Mze Ali Ahmed, made his entrance in style, dressed in a turban and robes lined with golden cloth.

Accompanied by men from his extended family, he took his seat for the prayers among rows of men, many wearing the traditionally embroidered mharuma scarf denoting their distinguished status.

The dowry intended for Ahmed’s bride was officially announced and he was saluted by ululating women resplendent in glitzy headscarves and dresses.

Elsewhere on the Grande Comore, the largest of the nation’s three islands, it was the big day for a couple based on the French territory of Reunion about 1,600 kilometres (1,000 miles) further east into the Indian Ocean.

In a family home in the town of Tsidje in the hills just outside Moroni, men helped the groom, 42-year-old Faid Kassime, put on a handmade black velvet coat embroidered with gold threads.

Accompanied by an entourage of family and friends and with an umbrella held over him, Kassime walked to the family home of his wife — whom he first married in 2012 — in a procession preceded by drummers and displaying cases of gold ornaments and jewellery as dowry.

“It’s an accomplishment,” Kassime told AFP. “I really wanted to carry out this ceremony to honour traditions, parents and the in-laws.”

Staggering sums

It can often take a couple several years after their first wedding, called the “Petit Mariage”, to accumulate the money required to host the second, more lavish event.

But, as costly as it is, the ceremony is valued for sealing the social status of a couple in the hierarchy of their community, said anthropologist Damir Ben Ali.

“It marks the end of a period of social apprenticeship,” Ali said. “It means that a person has followed all the rules that allow him to have some responsibility in the community … for making decisions concerning the community.”

A “Grand Mariage” can cost a couple their entire life savings, said Ali, who found in research in 2009 that the financial outlay then ranged between 6,000 and 235,000 euros.

“It has surely increased since then,” he said.

The spending is staggering for a nation where 45 percent of the population of under 900,000 people lives below the poverty line of around 100 euros ($116) a month, according to the National Statistics Institute. Remissions from the diaspora account for 30 percent of the national GDP.

The sumptuous attire worn by couples at the ceremonies reflect the outfits worn by sultans before the Comoros became a French protectorate in the 19th century, said Sultan Chouzour, author of the 1994 book, “The Power of Honour”.

“The ceremony is akin to enthroning a new king,” he said. “Here, everyone can be a sultan.”

New status

Kassime’s procession to the home of his 41-year-old bride, Faizat Aboubacar, illustrated the Comoros’s matrilineal system and its practice of matrilocality in which husbands move into the communities of their wives.

Aboubacar was overjoyed after her special day. “I am surrounded by my loved ones and that is all that matters. It is a beautiful moment,” she said.

The event announces to society that a woman’s social status has improved, said Farahate Mahamoud, one of the guests.

“She will be treated as a dignitary wherever she goes. At all ceremonies, she will have the right to speak,” Mahamoud said.

Aboubacar’s mother-in-law was proud that the couple had returned to the Comoros to uphold one of its pillar traditions.

“A continuation of our customs is a great joy — especially for children who were born in France, raised in France, educated in France or working in France to accept doing what we, as parents and grandparents, did,” said Maria Amadi.