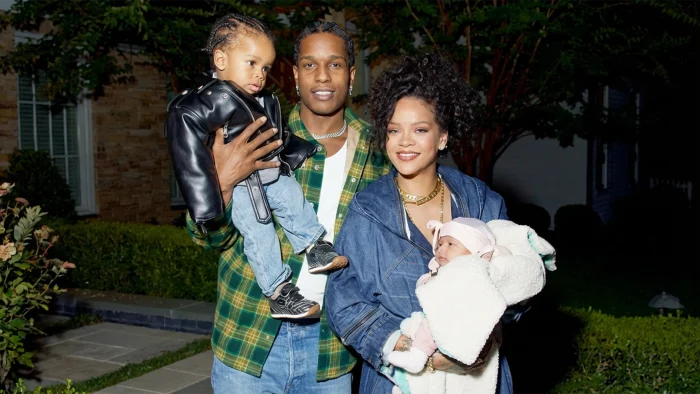

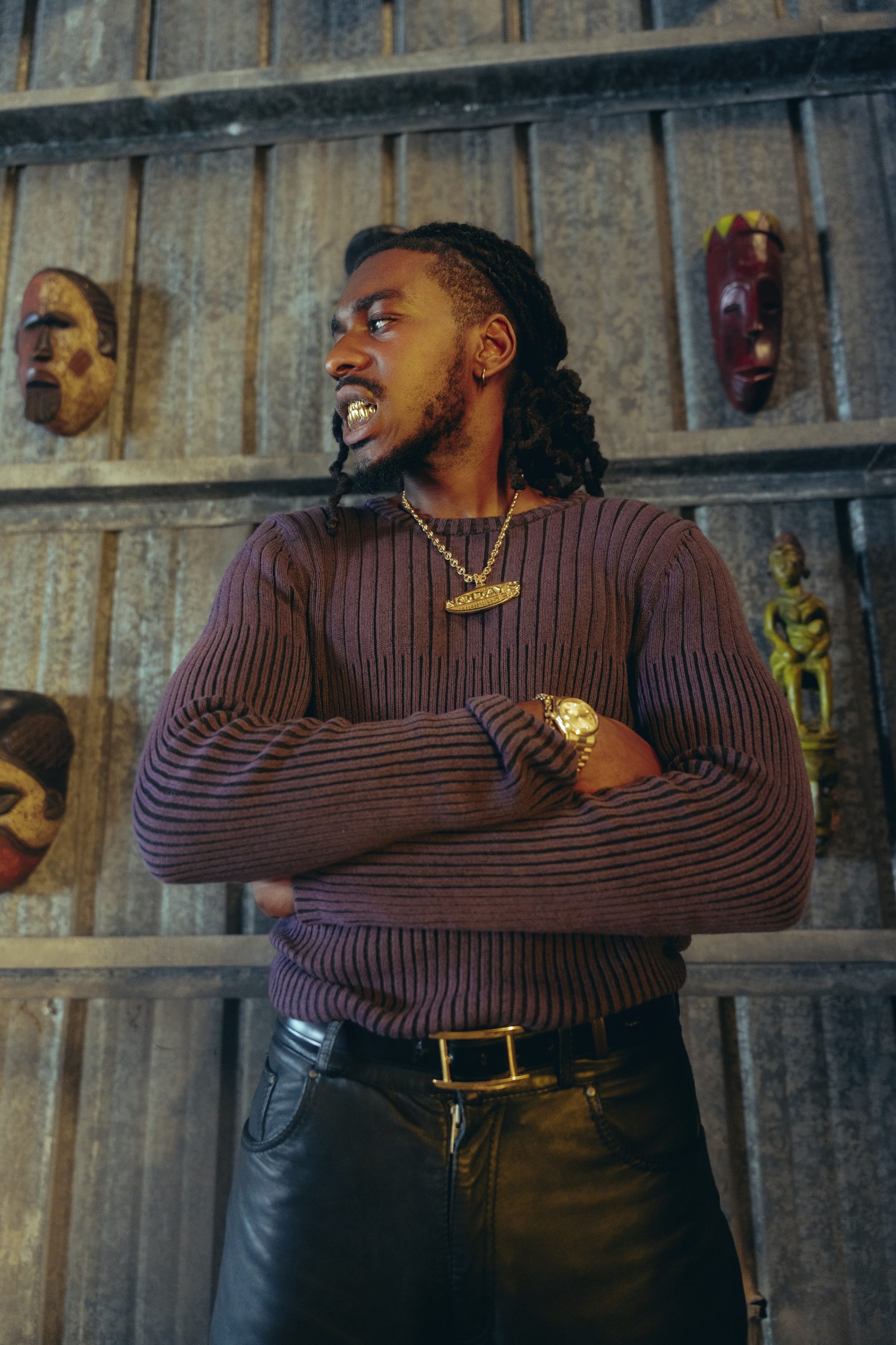

For British-Nigerian rapper Knucks, home is more than geography. In A Fine African Man, his most personal project yet, the MOBO Award winner traces identity, survival, and self-definition across London and Enugu, blending soul-rooted hip-hop with ancestral memory and lived experience.

For the award-winning British-Nigerian rapper, Knucks, home means something more than just a residence. It’s heritage and identity, reflected as mementoes that have since soundtracked his evolution as one of the UK’s hardest emcees since his 2015 breakout.

“If I didn’t come back to Nigeria, I might not even made it alive today, (sic)” he tells Guardian Music, recounting how his parents sent him to boarding school, for one year, in Enugu, circa 2007, after ceaselessly causing mischief in London. Upon returning to the UK in 2008, Knucks, born Afamefuna Ashley Nwachukwu, reignited his musical ambitions, navigating the emerging Hip-Hop fusions that had begun replacing Grime’s supremacy.

A couple of EPs and standout singles later, he released his debut album, Alpha Place, in 2022, properly documenting his experiences living on Alpha Street in London. The album later clinched the ‘Album of the Year’ spot at the 2022 Music of Black Origins (MOBO) awards, creating a solid build-up for his most introspective and heritage-driven record yet, his recently-released 13-track sophomore album, A Fine African Man (AFAM).

In A Fine African Man, he revisits the concept of ‘home’ and ‘identity’ again, finding muses from his golden moments in Nigeria, a time when he strongly navigated identity, heritage, and self-development. “Growing up, I used to trek from Trans-Ekulu to Abakpa Nike, after spending my bus fare on silly things like popcorn and cake. It was a crazy two-hour walk, and I did it often,” he said.

On the album, the 30-year-old rapper, popular for his soul/jazz-inflected boom bap Hip Hop, Drill and Grime, explores Igbo highlife music and Afrobeats strongly, weaving ancestral melodies with local instruments like the Oja and Ogene, and his signature soul motifs.

Catching up with Guardian Music, Knucks, delves deeper into his inspirations for A Fine African Man, tracing his early experiences surviving London and Enugu; exploring modern Hip Hop, after returning to the UK; connecting with Nigerian music, especially highlife and Afrobeats; as well as sharing his take on Nigeria’s growing Hip Hop scene, and his mission to continuously create authentic music.

What inspired the album, A Fine African Man?

I was already working on a different album, off the back of my last album, with an American producer called Kenny Beats. A year into working on that, I had some conversations with my managers, and they were talking about how music was heading in the direction of Nigeria, and Africa, and they were just trying to find a way to tap into that. I came back to Enugu for schooling when I was younger for one year. It was a boarding school. And I’d always known that the experience was a very pivotal one for me, and it was something that I would talk about in some way.

And even on my last album, I mentioned it on the final track Three Musketeers. I mentioned getting sent here and coming back to the UK, and how things were different. But I never really spoke about my time in Nigeria and how boarding school was for me. So I decided to make the concepts about me and that experience, and how it affected me and made me the man I am today. My last album, Alpha Place, gave people context of who I was at that point by showing where I came from; Alpha Place is literally the name of the street that I grew up on. My house was called Alpha House. So, in this sense, I felt like telling that ‘Nigeria’ story.

The last time I came back, before I visited recently, was when I was 15. I came back in 2023, almost 10 years after. So it’s a concept of me then and how I experienced Nigeria as a 12-year-old for the first time versus me now as a man, as someone who’s recognised, and how I experience Nigeria now. Also, it’s the acronym of my Nigerian name, Afamefuna. I felt like having it called a fine African man, instead of calling it AFAM, was a better way. I think it all ties in together because there’s a lot of identity and becoming a man narratives, and all of that stuff. My name is an important part of it all.

You came back in 2023 and recorded some field audio for this album. Tell us about that experience too.

In the song called Knuckles, I talked about how I often spent my bus fare on silly things like popcorn and cake, and I’d had to walk home. I would walk from Trans-Ekulu to my aunt’s housing estate in Abakpa Nike. Both places were not close at all. In fact, a cousin of mine did the walk recently, and he was stunned at how a 12-year-old me was doing the walk at that time.

So when I went back, and I was recording that junction, I was just taking in the sounds, all of those sounds and all of those experiences that I usually faced on that walk, because I did the walk at least four or five times back then. Walking back through all of these areas, I recorded loads of things, like some of the women selling, or the bus drivers. I wanted to catch them authentically, so that’s why I went there. I’m very big on authenticity.

What was your connection to Nigerian music then versus now?

So when I was here before, I picked up on a lot of Nigerian music. You’d be surprised because you don’t hear them on the album still. However, whether it’s the energy or the aura of some of these songs, they did shape me musically as well. For instance, I was here when Flavour’s N’abania came out. It was my favourite song at the time. And even though I didn’t understand everything that was being said, I kind of understood a little bit of it. And because my auntie was so religious, she was against secular music and didn’t really like us listening to it.

However, she bought me that Flavour CD on my birthday, and it just showed me how much she cared, even though she felt like it wasn’t the best thing to listen to. I listened to a lot of Tuface, Timaya, and P-Square. Right now, I’ve connected with a lot of artists, especially Igbo artistes like Jeriq. And that’s off the back of him being so glued to the UK music scene. Phyno, as well, also lived around the same housing estate I stayed at in Enugu. So there are a lot of authentic connections that came about.

You’ve explored several evolutions of Hip Hop music. What motivates you to stay fusion-focused?

Yeah, I think my style from the onset has been a mix of the music that I grew up listening to and loving, which are soul, jazz and all of that, and the music I listen to now, which is usually Hip Hop. So at first it was Hip Hop with Hip Hop kind of drums, but with soulful music in the background. Then, when trap music started, I shifted to trap but with 808s, bass, and soulful samples. Then, when drill came, I really liked it; but it’s a very dark genre, in terms of the things that they talk about and its sound.

So, I did what I always do, which was to put my soulful music there, but then use the drill drums. So, with my last album, I made the same drill and soul fusion, so that people know that it came from me. Now, in AFAM, I revisited the soul samples, but with African music. The difference with this one is that instead of me just doing soul and then putting Afrobeats drums on it, I added rap. So a song like Yam Porridge has Afroswing vibes, but I’m rapping on there. In a song like Pure Water, it’s got the soulful sound, but there are drill elements to appease the people who came off the back of the last album. I made sure that every style that I have, I added to this album. For me, it’s always a case of blending sounds to make something new, rather than doing my version of what everybody’s already doing.

Do you have any creative habits or typical processes?

I don’t really. Usually, it starts with me making a beat. In terms of inspiration, I get a lot from watching TV. For instance, I have a song called Los Pollos Hermanos, which is named after the restaurant in a show called Breaking Bad, which is one of my favourite shows. Then another song called Leon The Professional, which is based on a film called Leon The Professional, about a hitman. Even the artwork for AFAM is inspired by the Brazilian film City of God.

So a lot of my inspiration comes from TV and media that I just soaked in. In terms of processes, something that usually helps me with writing is producing. So, I make beats, and if I want to write something or make a new song, I’ll start by listening to samples, listening to music, and making a beat. And then off the back of making the beat, the beat dictates what vibe I should go with in writing. If it’s a piano sad beat, then obviously I’m not going to be rapping about praising Jesus. So, the mood of the beat dictates what I will be talking about, or the direction of the song.

What was your most intense recording session in making AFAM?

I don’t know if there’s one that was way more intense than others, but I will say one of the more pivotal ones for me was the session where I created Masquerade. It was in Jamaica. I had a writing camp there, in a place called G Jam Studios. It’s a very popular place where people go to make albums and whatnot. And I had been working on a beat.

There’s a producer I’d also been working with called Beat Butcher, who makes samples from scratch. And in one of the samples he made, I found a part of it that I liked. I just put it on loop, and that melody turned out to be the song, Masquerade. It was looping so much that when I added drums, it did not sound right. I took the drums out, and I just left it like that. That song came off the back of me having writer’s block and not being able to move forward with the album. I was at a standstill. And after playing that loop over and over again and making that song, I felt instantly that it was going to be the intro to AFAM.

With the rise of drill music in Nigeria, what’s your take on artists localising its spread here?

It’s good for the UK, because for a very long time, our music wasn’t being taken seriously, and it wasn’t global. And I think it’s only in the past maybe five or six years that the world has really been looking at our scene. Also, the TV show Top Boy kind of put everybody’s eyes on us. So I think it’s good on that front, and then on the second front, it’s good that the Nigerian youth have found a way to express themselves. It is a very good thing, and it’s only going to flourish. People like Jeriq, Highstar Lavista, and many others are pushing at the forefront.

If you could go back in time to change your past, would you prevent yourself from schooling in Nigeria?

I say this a lot, and people think I’m joking, but I’m scared to know what would have happened, who I would have been if I never came here. It’s pure fear. I don’t even know if I would still be alive. And that’s me being honest. So without a shadow of a doubt, I wouldn’t change it. Coming back to Nigeria when I did saved my life.

If you weren’t doing music, what else would you have done?

Before I was doing music, I was an artist. I studied animation in university. So, probably something within that field, maybe a graphic designer, or one of those people who make games working for Pixar, or something like that.

Finally, what would you want people to experience from your artistry in the long run?

My authenticity…someone who’s just themselves, someone who’s fighting for people who feel like they need to act or portray a certain character to be respected or to be seen. I think I’m fighting that battle to show that you don’t have to be a gunman or to be this or anything else; you can be yourself. That’s how I became me.