Nigerian literature remains the most constant redeeming factor for Nigeria since independence in 1960. The Nigerian experience has been chequered and painfully tragic in view of our many failings despite being one of the most endowed spaces in the world. The road to independence was pot-holed by many self-destructive schemes arising from inter-ethnic tensions as the colonizers also showed their hands in many of the pre-independence crises by way of instigating one ethnic nationality against another to strengthen the hold of Britain on Nigeria even after independence.

Not long after independence the house that Britain built and named Nigeria fell apart and to this day the entity that has been described as “a mere geographical expression” has become nothing, but a tottering giant. The Nigerian house has fallen, so says Karl Meir, but its literature and the criticism woven around it remain strong and inspiring as they continue to put Nigeria in global reckoning in matters of the imagination and the cerebral.

The birthing of Nigerian literature in the period just before independence was not accidental. It was part of an inscrutable scheme that came to be in anticipation of the redemptive role the literature will play in post-independent Nigeria. Literary chroniclers will constantly refer to the liberating role the emergent literature played in the struggle for the nation’s independence. As the colonizers denigrated Africans as subalterns in every sphere of life it fell on Nigeria’s pioneer writers to write and correct such a wrong standpoint and put our story in the correct perspective.

The most defining moment for Nigerian literature in that heady moment was the publication of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart in 1958. The novel makes a bold statement which foregrounds and frames not only the existence and validity of an African culture, but the audacity and panache with which the story was told earned Africa a significant measure of respect. Of course Achebe’s engagement in the novel is a deliberate attempt to inspire confidence and confer dignity on the African. This tendency eventually inspired many other writers from Nigeria and other countries in Africa to write “our story”, reclaim the historical imperative and confer dignity on the continent.

Since the publication of Things Fall Apart nearly sixty years ago Nigerian literature has flourished and earned well deserved accolades including Wole Soyinka’s winning of the Nobel Prize in 1986. Since then the most significant thing people the world over remember Nigeria for at every forum including the gathering of heads of states is the phenomenon called Nigerian literature. Yet those who rule Nigeria have an incurable apathy for the literature. Besides Achebe and Soyinka, the list of Nigerian writers who have brought fame to the country is endless. Through the adroit articulation of their imaginative configuration the writers have signposted Nigerian literature as the most credible item of the nation’s cultural and knowledge production.

The enduring tradition of critical scholarship for which Nigerian scholars and critics are well known has gone a long way in complementing the literature and ensuring that it evolves in more ways than one. Since the late 1960s when Nigerians started earning higher degrees in English and allied disciplines the sphere of scholarship aptly codified as literary criticism has given immense illumination to Nigerian literature. The likes of Sunday Anozie, Dan Izevbaye, Abiola Irele, Romanus Egudu, Charles Nnnolim, Steve Ogude, Omafume Onoge, Biodun Jeyifo G. G. Darah, the troika of Chinweinzu, Jemie Onwuchekwa and Ihechukwu and Madubuike (the list is interminable), have written critical discourses which affirm the place of Nigerian literature among world literatures.

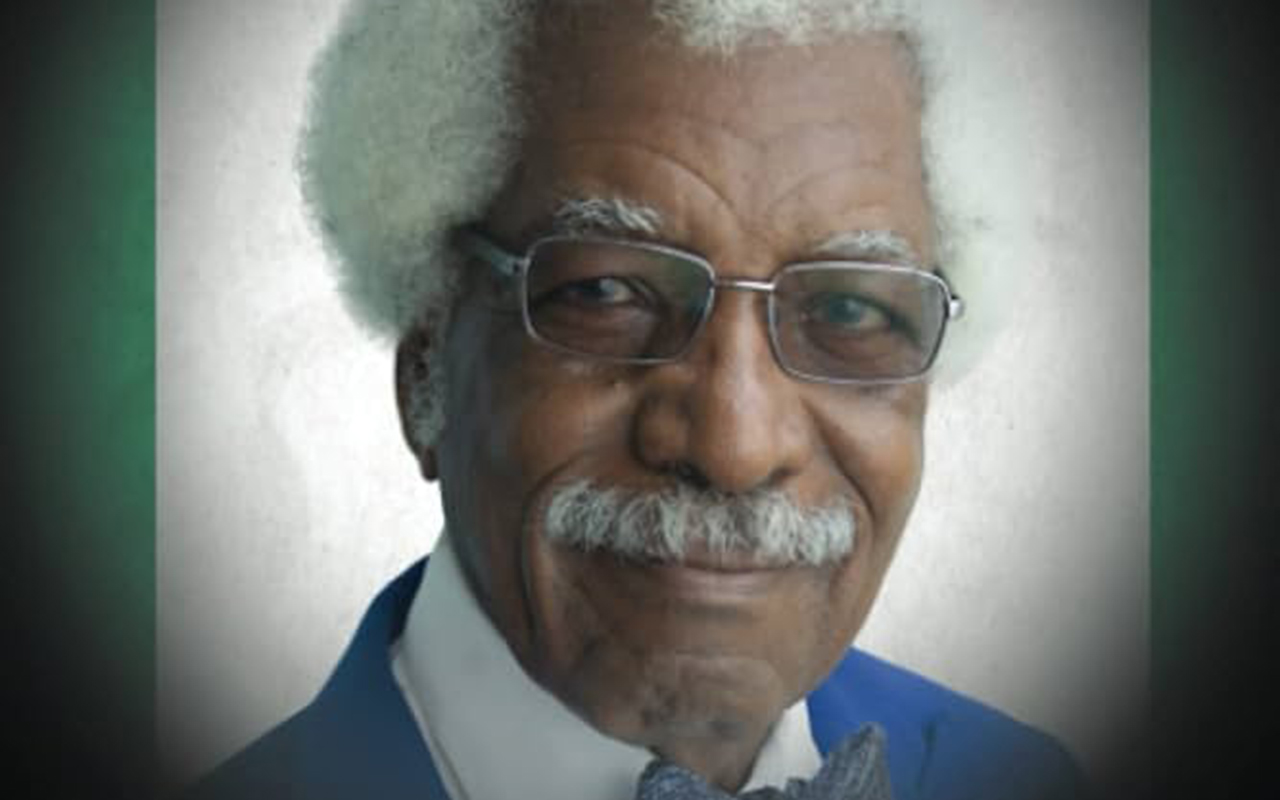

Interestingly, there are some Nigerians noted for being ambidextrous as they found forte in both creative writing and literary scholarship. These are primarily writers who are also university teachers who needed to balance criticism with creativity in order to survive in the academia and gain professional ascendancy. These come with various labels such as writer-critics, scholar-poets and what have you. Good examples include Femi Osofisan, Tanure Ojaide, Niyi Osundare, Olu Obafemi, Remi Raji and more. An outstanding name in this category is Professor Isidore Okpewho who passed away on Sunday 4th September 2016.

Born in 1941 to an Urhobo father and an Asaba mother, the late Professor Isidore Okpewho hailed from Delta State. Isidore Okpewho was a wiz kid during his earliest academic outing in primary and secondary schools. He went on to the then University College, Ibadan to consolidate on his sterling academic record with a First Class honours degree in Classics the most arcane of disciplines. Okpewho began his working career with Longman which was then one of the most formidable publishing firms. However, the cerebral itch saw him travelling to the United States of America (USA) for postgraduate studies. While in the US he pitched his tent at the University of Denver, Colorado where he earned in doctor of philosophy degree comparative literature.

Having taken all the academic degrees there were to be taken Okpewho started his teaching career with the University of New York at Buffalo where he taught from 1974 to 1976. He embarked on a homecoming to Nigeria in 1976 and nestled at the University of Ibadan, the nation’s premier university. At Ibadan, Okpewho was in company of kindred spirits in the stellar company that at one time or the other included MJC Echeruo, Ayo Bangbose, Ayo Banjo, Obaro Ikime, Dan Izevbaye, Abiola Irele, John Atanda, Peter Bodurin, Niyi Osundare, Femi Osofisan, Abednego Ekoko, Sam Asein, Egbe Ifie, M. Y. Nabofa, Godwin Sogolo, Remy Oriaku, Emevwo Biakolo, Harry Garuba and a host of others who made the university’s Faculty of Arts the leading enclave for humanistic scholarship in Africa. It is also worth mentioning that Okpewho’s arrival at Ibadan and the time he taught there coincided with the university’s halcyon years when Midwesterners (now of Delta and Edo States) not only awed colleagues and generations of students, but also set the pace for academic exploits in almost every discipline. Besides, Onoge, Izevbaye, Irele, Ikime, Sogolo and others already mentioned, the likes of Peter Ekeh, Onigu Otite, David Okpako, ST Bajah, Awele Maduemezia, Frank Ukoli and a host of others defined the academic prowess for which Ibadan was globally famous.

Okpewho’s reputation in the foregoing scheme rested on his gift as a creative writer and on the uncommon assiduity he brought to scholarship. Okpewho saw himself first as a creative writer before being a scholar. This probably informed the title he chose for his 1989 inaugural lecture A Portrait of the Artist as a Scholar. However, an evaluation of Okpewho’s scribal input will reveal a balancing of creativity and scholarship. Yet some argue that his scholarship dwarfed his creativity. The title of this essay A Portrait of the Scholar as an Artist is a deliberate inversion enabled by the thinking that Okpewho’s scholarly output outweighed his creative oeuvre. Okpewho’s greatness inheres in his masterful engagement with both creative writing and scholarship. His inaugural lecture with the title reminiscent of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Youngman adumbrates his uncommon synthesis of scholarly research and imaginative writing a thrilling experience that reincarnates in his last novel Call Me By My Rightful Name.

Okpewho’s academic exploit helped in giving fullest illumination to the study of literature at Ibadan where he also taught creative writing. Partnering with the distinguished poet, Niyi Osundare who taught the poetry aspect of creative writing, Okpewho held aloft the imaginative template of prose fiction writing and generations of students emerged from those classes as writers of note in the same way he inspired many more to excavate the oral traditions of their people.

In the realm of Nigerian literature Okpewho blazed a trail when he published his first novel The Victims (1970). The novel which is unarguably the curtain raiser for the genre of social realism in Nigeria, mirrors the crises inherent in polygamy when the head of the household lacks the financial wherewithal to run it. The plot revolves round the family of Obanua the husband of Nwabunor and Ogugua. Things reach a head when Obanua gets incited by his mother to marry a second wife as a result of Nwabunor’s not conceiving for three years. Obanua marries Ogugua who already had twins for a Portuguese. The domestic crises spin out of control and assume a tragic proportion when Nwabunor’s diabolic scheme kills the entire family with the notable exception of the helpless Obanua. Okpewho’s effort in this first novel is very significant in his departure from the representation of the past and post-independence crises (which were the fad among writers at that time) to mirror the lives of the hitherto unrepresented mass held down by poverty and annihilated by intrigues engendered by polygamy.

His second novel The Last Duty (1976) is also a path-clearing departure from the dominant narrative pattern woven around the Nigerian civil war. Instead of depicting the political and physical dimensions of the catastrophic war he embarks on a psychological portrayal of how the war created victims and villains in homes and families far away from the hurly-burly of the battlefield. It is the story of Oshevire, his incarceration and tragic death after he is released at the end of the war. The novel depicts envy, malice, betrayal, intrigue and death outside the theatre of war. Okpewho brings a uniqueness to the narrative by creating characters whose confessional statements constitute the narrative thread. Every character is made to recount his/her experience as he/she sees it. In the process the novel privileges the stream of consciousness technique in the psychological depiction of the characters. The characters are unique as they represent the mood and compelling circumstances of war. Oshevire gets implicated by his business rival Toje who ropes him into a phantom plot leading to his incarceration. In Oshevire’s absence his wife Aku from the enemy tribe and their son Oghenovo try to hold out, until her defence gives way to hostility, hunger and emotion. Oshevire returns home to meet the unsavoury condition and for him the only option, his “last duty” is self destruction that will obliterate the shame brought on his household.

In Tides (1993) Okpewho focuses on the Niger Delta eco-crises through the narrative mode at a time when it was only fashionable to do so in verse. His is probably the first novel to interrogate the problem of environmental degradation in the Niger Delta and imagined strategies for combating the menace. Constructed around an epistolary framework, the novel throws up two protagonists Tonwe and Dokumo both of them journalists who get sacked from the newspaper Chroncle. Dokumo decides to remain in Lagos while Tonwe returns to the Delta. The novel’s crux is the environmental degradation as a result of the activities of foreign oil companies. The protagonists are incensed by the threat to the people and the homeland and are compelled to join forces and check the menace. However, the self-appointed task is fraught with dilemmas all the way. The characters have to contend with dual and antagonistic choices between collective good and personal benefit, patriotism to the state and professional allegiance, national aspirations and regional survival among other contending forces.

His last novel Call Me By My Rightful Name (2004) is an affirmative statement on the homecoming motif. A classic return to native land and self-discovery yarn about Otis Hampton an African American, the novel encodes a journey from America to Nigeria. Prodded by disturbing psycho-spiritual forces Otis embarks on a quest which reconnects him with his kin from a generation that was debilitated by slavery and communal intrigues. Otis an American football star is almost on the verge of psychological and physical attrition before embarking on the journey to Nigeria. However, on reaching the spot where his great grandfather was enslaved he is possessed by a new surge of energy which puts him on the path of recovery. His kin recognize him and a series of ritual observances restore him to vibrancy as he enters the phase of self-reclamation. He is renamed Akin, “his rightful name”, and he survives new communal schemes aimed at liquidating him before returning to America to join the rights movement of the 1960s. Again this novel is as unique as Okpewho’s earlier ones because its preoccupation which is the return to Africa motif a consequence of the Trans Atlantic Slave trade was hitherto considered as an exclusive preserve of African American writers. In this novel Okpewho’s monumental field work research and experience are brought to bear on the intricate and almost exhilarating homecoming narrative.

An appraisal of Okpewho’s output will remain inconclusive if attention is given to his sublime creative works at the expense of his audacious critical interventions. Many people will remember him as a towering figure in the study of African oral literature and only the name of Ruth Finnegan compares with his in that field. Okpewho’s groundbreaking works in the field include The Epic in Africa (1979), African Oral Literature (1992), Once Upon A Kingdom: Myth, Hegemony, and Identity (1998) and Blood on the Tides: The Ozidi Saga and the Oral Epic Narratology. He also edited Oral Performance in Africa and The Heritage of African Poetry (1985). Reading these profoundly insightful books by Okpewho is always a delight as they attest to his prodigious intellect. The issues raised in Okpewho’s books on oral literature in Africa can be read on many platforms beyond literature. The relevance of the texts encompasses the fields of history, philosophy, anthropology, archaeology, sociology and more. The books also rupture many Western assumptions regarding the critical and imaginative faculties of the African. This is so because Okpewho’s fieldworks which formed the bases of the books attest to the existence of an African culture, a rational pre-colonial society, creative and imaginative astuteness and other observances which foreground humanity. His endeavours did correct many erroneous views on African oral tradition and reposition it as a fertile ground for critical and creative engagement.

Okpewho left the University of Ibadan for the US where he taught in some of that country’s most prestigious universities. But that was after he wrote the famous University of Ibadan anthem “The Fount”. He was in the first order in creative writing and critical scholarship. The very significant prizes and awards with which he was decorated testify to his remarkable greatness as a writer and scholar. Besides getting festooned with Nigeria’s highest accolade for intellectual acclaim the Nigerian National Order of Merit (NNOM), in the year 2010, he also won many significant fellowships such as the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (1982), Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (1982), Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford (1988), the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard (1990), National Humanities Center in North Carolina (1997), and the Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation (2003). Okpewho was elected as Folklore Fellow International by the Finnish Academy of the Sciences in Helsinki (1993) and served as President of the International Society for the Oral Literatures of Africa (ISOLA).

He not only received a D.Litt in the Humanities from the University of London, his creative works won him the 1976 African Arts Prize for Literature and the 1993 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize Best Book Africa.

In the countdown to the return of “The Guardian Literary Series” I had planned to request Professors Isidore Diala and Nduka Otiono to do an essay each on Okpewho. While one was to evaluate his creative works, the other was to engage his scholarship. However, I didn’t get to make the request before his passing on. Thus the compelling urgency of editorial deadlines necessitated my writing this tribute essay.

Prof. Isidore Okpewho is survived by his wife, Mrs. Obiageli Okpewho; his children: Ediru, Ugo, Afigo, and Onome. He answered the final call on Sunday 4th September 2016. Uhanghwa and Aridon the Urhobo gods of inspiration and memory respectively found a worthy brain and hand in him. Okpewho said a loud “yes” and his chi the Ibo personal spirit affirmed it. Okpewho represented “a portrait of the scholar as an artist” or maybe we should concede it to him “the portrait of the artist as a scholar”. Professor Isidore Okpewho tode….ooooo….akpokedefaoooo………

• Dr. Awhefeada teaches Literature at the Delta State University, Abraka.