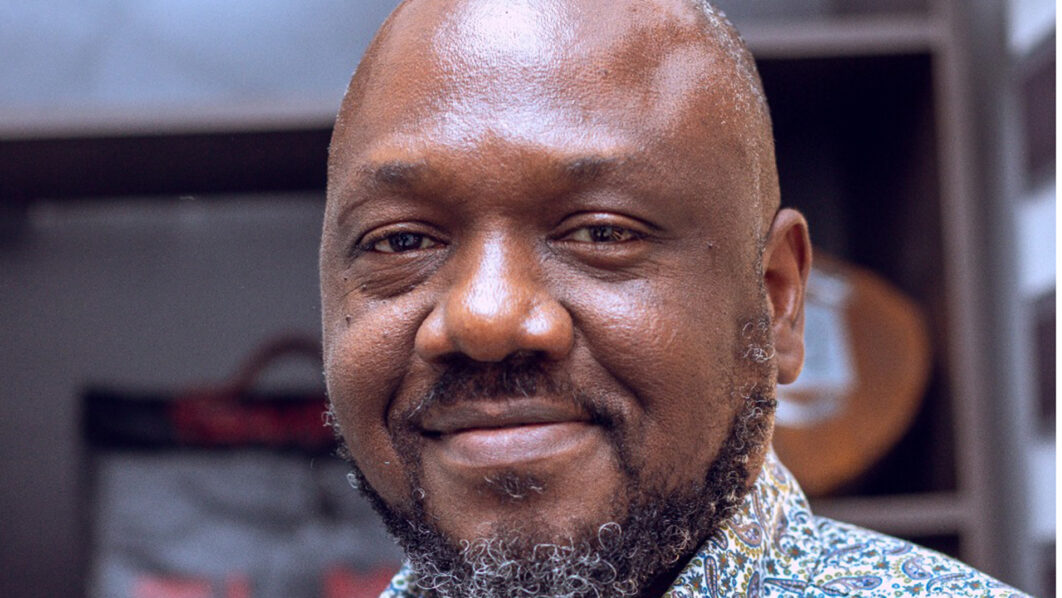

Dr Sunday Udo is the National Director of Leprosy Mission Nigeria. He spoke with NKECHI ONYEDIKA-UGOEZE, on the challenges of managing leprosy cases in the country, and ways the government should intervene.

What is the leprosy situation in Nigeria?

Leprosy remains a significant public health concern in Nigeria. It is estimated that over 400,000 Nigerians are currently living with the disease or its long-term consequences, spread across approximately 61 leprosy villages nationwide.

These individuals have often endured severe complications and disabilities, which are primarily the result of delayed diagnosis or inadequate treatment. Many of them face various challenges, including physical disabilities, social stigmatisation, and limited access to resources, all stemming from the impact of leprosy on their lives.

How many cases do we record in Nigeria yearly and which states report the highest number of leprosy cases in the country?

Each year, Nigeria records between 2,500 and 3,000 new cases of leprosy. These are individuals who have not been previously diagnosed with the disease, representing fresh infections rather than relapses or ongoing cases.

The number of leprosy cases reported in any area is directly related to the level of effort put into active case finding. If leprosy is not actively searched for, cases are unlikely to be detected. States reporting the highest numbers of cases, such as Zamfara, Niger, Benue, and Ebonyi, are places where significant work is being done on active case detection.

Currently, Nigeria identifies approximately 2,500 to 3,000 new cases of leprosy each year. Among these, over six per cent are children under the age of 14, which is significant because leprosy is neither hereditary nor transmitted from mother to child.

This indicates that these children contracted the disease from their environment, providing evidence that leprosy transmission is ongoing in the country.

Additionally, more than 40 per cent of the newly identified cases are women. This has devastating implications, as many women affected by leprosy face severe stigma, which can lead to the loss of their marriages and worsening economic conditions. The ongoing drug shortages—lasting over 11 months—further compound the suffering of individuals affected by the disease.

Another concerning data is that over 15 per cent of new cases are diagnosed with visible deformities. This means that these individuals were not diagnosed or treated early enough, allowing the disease to cause severe complications such as clawed hands, blindness, collapsed noses, chronic ulcers, or even amputations. These deformities severely impact their quality of life and increase stigma and exclusion. Leprosy transmission persists due to several factors, including poverty, malnutrition, limited Access to Healthcare, stigma and misdiagnosis and poor Awareness.

While active case finding has uncovered many cases in states like Zamfara, Niger, Benue, and Ebonyi, the persistent issues of poverty, stigma, and inadequate healthcare continue to drive transmission and delay early diagnosis. Addressing these challenges is critical to reducing the burden of leprosy in Nigeria.

What are the challenges faced by people living with leprosy in the country? Why are they confined to colonies?

The challenges faced by people affected by leprosy are numerous, primarily stemming from the social consequences of the disease. Stigma and discrimination remain the most significant challenges, fueled by unfounded fears and misinformation about leprosy. Many people mistakenly believe that leprosy is highly contagious, leading to fear and avoidance, especially when they see someone with deformities caused by the disease.

Even hearing that someone has leprosy can evoke fear, as people erroneously think they can easily contract it. However, leprosy is not highly contagious. While it is an infectious disease, meaning it can be transmitted from one person to another, it requires prolonged and close contact with an untreated infected person for transmission to occur.

This is different from diseases like COVID-19 or the common cold, where transmission can happen quickly and easily in shared spaces. Leprosy does not spread through casual contact, such as shaking hands or being near someone who has the disease.

The stigma and discrimination associated with leprosy lead to social exclusion, unemployment, and limited access to medical care and education. For instance, children of those affected by leprosy are often denied admission to schools. This perpetuates a cycle of poverty and exclusion for those affected.

Historically, the establishment of leprosy villages or colonies was driven by the absence of effective treatment. At that time, isolation was the primary strategy to prevent the spread of the disease.

Countries set up these colonies to separate individuals affected by leprosy from the rest of society. However, with the introduction of Multi-Drug Therapy (MDT), leprosy is now completely curable, and isolation is no longer necessary.

Despite this, many of these colonies still exist today because the residents have built their lives there over time. They have formed families and communities, and for many, there is no alternative place to go.

Some of these communities are undergoing positive changes, becoming more integrated and inclusive. For example, the leprosy settlement in Kwali, within the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), was established by the government as an integrated community. It was designed to rehabilitate individuals affected by leprosy while allowing non-affected persons to live and interact freely with them.

This approach represents a hopeful future where individuals affected by leprosy can live freely without fear of stigma or discrimination. Leprosy is no longer a public health threat in terms of contagion, thanks to effective treatment, and there is no need for isolation. Educating the public about this reality is crucial to overcoming fear and fostering integration.

What is the major challenge facing the leprosy response in the country?

Although leprosy is a curable entity, we have a challenge in Nigeria at the moment. For the past 11 months, there has been a stock-out of MDT in-country.

Nigeria is unable to secure MDT medications and this delay, for me, I think is more from procedural bottlenecks. The challenge was that the company that was supposed to produce these drugs continuously failed to respond to the requirements of NAFDAC and that now led to the delay.

However, I got a recent report that NAFDAC has finally agreed to allow the drugs to be tested and released. Over 3,000 persons are waiting to take these drugs, including more than 800 children who are waiting for these drugs as we speak. Honestly, this is one of the worst experiences since my almost 20 years of working in the field of leprosy.

Though leprosy is not contagious, but infectious, an untreated leprosy patient who has a lot of Vaseline in his body can easily transmit it to not less than 10-15 people, if not found on time but here we are, finding them on time, but we can’t treat them because the drugs are not there. This is a serious issue.

For me, it’s a serious human rights concern as well. And my pain is also the fact that it was delayed for so long. The government should make these drugs available. We understand that NAFDAC wants to keep its standards, and ensure what comes in is good and that is because we are trying to avoid antimicrobial resistance, but at the same time, you don’t now hold on to a policy or a process to the detriment of your people. There must be a way out, either they sanction those people, find a new donor or whatever, something ought to have been done.

NAFDAC appointed a laboratory in India, called Quantrol, to test and verify the authenticity of the drugs. Sandoz, the supplier, was responsible for sending drug samples to Quantrol for testing. However, due to issues between Sandoz and Quantrol, the correct samples were not provided for testing. This failure likely caused the delay.

In response, NAFDAC has now decided to allow the drugs to be imported into Nigeria without prior testing by Quantrol. Once the drugs arrive, NAFDAC will conduct the necessary tests locally. If the drugs pass the quality tests, they will then be approved for distribution.

Does Nigeria have enough trained healthcare personnel for the care and treatment of leprosy?

No. There has been a noticeable decline in expertise in leprosy, which is a serious concern both locally and globally. Many healthcare professionals with specialised knowledge in leprosy are ageing and retiring, and there is a significant shortage of young professionals being trained or incentivised to take their place. Many young professionals are opting to pursue other fields of medicine.

Only a few medical schools expose their students to leprosy, which means many new graduates lack the knowledge needed to diagnose or manage the disease effectively.

Efforts are being made to address this gap. For instance, there is a national training centre in Zaria, and the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations is working with the Federal Ministry of Health to secure funding and provide more training opportunities.

Don’t you think, there is low level of awareness about this disease?

The low level of awareness about leprosy largely stems from stigma, misinformation, and insufficient funding to effectively disseminate accurate information. While there is a World Leprosy Day, activities to sustain awareness throughout the year are limited.

Health education campaigns are scarce, and leprosy is inadequately integrated into broader healthcare programmes. These gaps contribute to leprosy being deprioritised, especially when compared to diseases like tuberculosis (TB), which receives significantly more attention and funding.

Years ago, Nigeria achieved the national leprosy elimination target of less than one case per 10,000 people. However, progress has since stalled. The original WHO programme aimed at eliminating leprosy as a public health problem and focused on reducing cases to this level, which would ideally lead to the natural disappearance of the disease.

Governments mobilised resources to meet this target, and once countries reached it, many assumed the problem was resolved. As a result, funding and efforts were scaled back, surveillance systems were not established, and no post-elimination plans were implemented. This led to a resurgence of leprosy in many areas, undoing much of the progress.

What is the level of implementation of Nigeria’s zero leprosy roadmap and action plan?

To be honest, the implementation of the national leprosy plan has not started as effectively as it should, which is disappointing. We are still in the process of finalising the document, despite its development beginning years ago. This delay highlights the lack of priority and attention given to leprosy in Nigeria.

The plan, developed with funding from the Global Partnership for Zero Leprosy, was designed because Nigeria remains one of the 23 high-burden countries still recording over 1,000 new cases of leprosy yearly. As one of the countries with the highest leprosy burden globally, Nigeria was selected to create this plan for the period 2023 to 2030. However, as of 2025, the document is yet to be finalized and fully implemented, which is a missed opportunity to make significant progress against leprosy.

Nigeria is at a pivotal moment where it has the potential to eliminate leprosy. Other countries, such as Sri Lanka, have successfully eradicated leprosy, so there is no reason why Nigeria cannot achieve the same. We have the tools, expertise, and the will to make it happen. The new WHO framework for zero leprosy, which focuses on zero disease transmission, zero disability, and zero discrimination, provides a clear roadmap to achieve this goal.