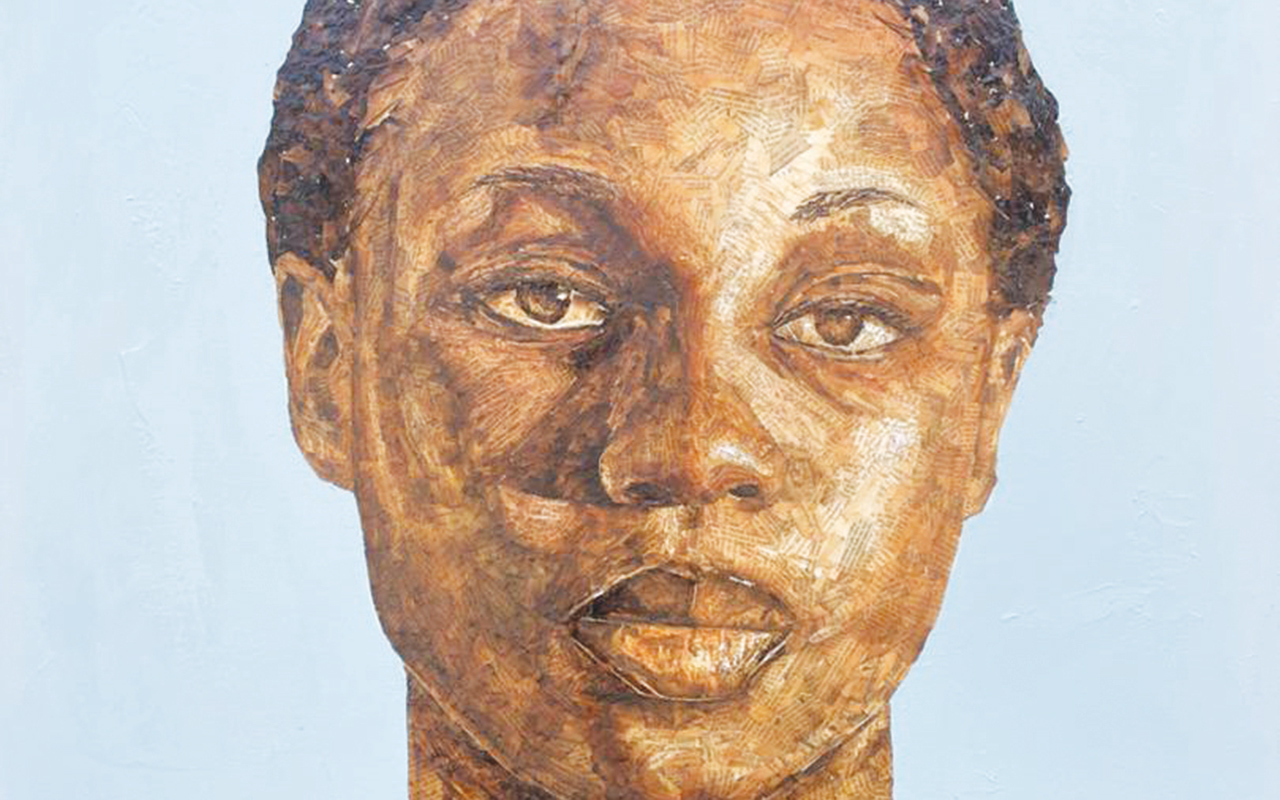

Sola Adeyemi is a brilliant theatre technician. He is very good at stage lighting, scenography and set construction. Directing plays is another excitement to him. Theory and criticism is last option.

His journey into theatre practice began after a stint with law, but as fate would have it, he found himself deploying chisel, hammer, clamp, craft knives, saws and Allen keys.

A protégé of the late Dr. Sumbo Marinho, he flowered to become a ‘student consultant’ for major shows on campus. That was Sola Adeyemi of University of Ibadan.

Today, he is a theatre theoretician, critique, drama teacher and venerated scholar. His creative side has become subsumed in theory and criticism. He now speaks only the language of dramaturgy: Elements, forms, content and styles.

Recently, he was elected the president of African Theatre Association (AfTA), an association of theatre academics and practitioners in the continent and diaspora, which he believes is an elegiac memorial to the period he led Association of Theatre Arts Students, University of Ibadan, 32 years ago.

“Has it been that long?” he asks.

“Well, leadership ethos are the same everywhere, and I believe the qualifications one needs are fixed: ability to be a good listener, to respect other people and show compassion and understanding to the immediate and remote causes that people believe in. It also helps if you love what you do, in my case, the whole essence of theatre and performance,” Adeyemi says.

He is not afraid of responsibility AfTA has thrust on him. He says, “the secret to life is to have no fear, according to Fela. I have already seen today, and therefore, fear no tomorrow.”

The Director of Drama, as well as, Head of Department of Drama at the School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing, University of East Anglia, England, continues: “Leading theatre practitioners is not dissimilar from directing a show and being part of a team. It is not a one-man show; it is a collaboration to achieve a defined goal. In this case, our goal is to advance education, practice, and research into African theatre and performance through our yearly conferences, symposia, practice, events, and publications. AfTA – the African Theatre Association – is an international not-for-profit membership organisation open to scholars and practitioners of African theatre and performance. But, you are right, the foundation of most of what we achieve lies in our training as students. ATAS was a good training base.”

His researches are in world theatre and performance studies, African Theatre and Performance, African Literary Studies, intercultural performance culture; contemporary British theatre; postcolonial literature and theatre (and the themes of decolonial and Global South studies); and diasporic African and black British theatre in its exploration of the politics of identity.

Currently, he is working on Dramatising the Postcolony: Nigerian Drama and Theatre and Laughing from Both Barrels: New Satire in Modern African Performances.

Adeyemi has degrees from the University of Ibadan, Nigeria; Atelier Dramatique du Golfe de Guineé, Cotonou, Bénin Republique; University of KwaZulu-Natal (now University of Natal), Pietermaritzburg, South Africa; University of Leeds, UK; and University of Greenwich, UK.

He has also held the following fellowships: International Research Centre, Interweaving Performance Cultures, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany (2017-2018); Ibadan Literary Society, Ibadan, Nigeria (2016-2021); and Africana Institute for Creation, Recognition, and Elevation (AICRE), University of California, Irvine, USA (2018-), so, his vision for the association is round. He is convinced he is going to lead it responsibly and very well.

“My interest was not in the Presidency, but rather in the development and advancement, and promotion, of African Theatre and Performance. It is a shared interest, which led to the formation of the association in 2006 by theatre academics and practitioners such as, Osita Okagbue, Samuel Kasule, Jumai Ewu, Kene Igweonu, Oladipo Agboluaje, Duro Oni (who is now a Life Member), the late Dr Victor Ukaegbu, Mufunanji Magalasi (of Malawi), and so many others,” says the co-editor of African Performance Review (APR) and on the editorial board member of Africa Book Link.

According to him, “at the inaugural meeting in 2006, we established to make the promotion of theatre and performance in Africa the focus of our teaching and practice, and, with members from many countries in the world, this has led to several new courses on African theatre. So, really, it’s not about what we are now going to do differently, but what we are going to continue doing better and bigger.”

Adeyemi reveals, “we have a journal, which we are going to move online into Open Access to give more visibility to new work in Africa and to allow for wider circulation. We are going to move the association closer to the ground in Africa by working more closely with universities, organisations, and practitioners all over Africa, and increase our presence in the northern part and the French speaking parts of the continent. We want to decentre African theatre and remove the relevance of the Global North in defining us. With some members of the association, we are already working on researching modern festivals and performances in Africa, and recuperating our cultural practices.”

You want to know the kind of strategy required for this role and major challenges he foresees for an association such as this that is diasporic in nature? He has this to say: “Simple. Work with people, as a team. We have a vision. My intention is to continue working with the members, and to increase membership of course. Nothing different from what I have been doing for the past 32 years, as you reminded! With team effort, our challenges can be overcome. The major ones are the issue of decoloniality, of leading our theatre practices as Africans instead of responding to the agenda set by the Western practice.”

He reveals, “this agenda, as you know, is always colonial, and always seeking to poorly compare our theatre and culture to those of the Western spaces, in particular, the British and the French. We need to develop conversations with Africans while maintaining the relationship with the rest of the world. Why are Brazilian and Trinidadian carnivals, for example, not studied in Ibadan for points of reference and association? Why is Afro-Ecuadorian Marimba Performance not given much attention in Kampala? Must we always respond to Shakespeare, to Racine, to Moliere, to the Greeks? Another challenge is publication of our research on African theatre, where we currently mostly have gatekeepers who are not familiar with our work, and therefore, reject our research in the process of ‘peer reviewing’ by non-peers. Gatekeepers can keep their gates; we are going to build our own edifices without gates!”

With the realisation that there is a lot of work to do and knowing there are thousands who feel the same way, he says like the Sahel grass, “I feed on the early morning dews. I grow on the inspiration provided by my leaders, my teachers, my friends.”

FROM the creative side as a poet and dramatist, Adeyemi has become more involved in academics and criticism, what could have led to this?

“Ah! You remember! Well, I still write, constantly. Although most of my writings these days are critical essays, I’m also working on volumes of poetry. I have rendered my grandmother’s story as a poem. She was one of the few of her generation, who could read and write Ajami script, which she picked up as an itinerant trader more than a century again. I am also into translations, working with Wangui wa Goro (who translated Ngugi’s early Kikuyu works into English) to translate some of Ngugi’s work into Yoruba. But I have not forgotten drama, only that it’s difficult to find relevance to some of our concerns, though we never give up. I keep going back to the treatise I wrote for The Tribune in 1993 – Towards a Theatre of Relevance. We need to continue being creative, incessantly.”

WRITING always energises him. He writes when he is exhausted to rejuvenate. He reads as he breathes and writes from reading.

To him, “writing is a nourishment.” He continues, “by running away from administrative and social duties! But seriously, I don’t allow anything to affect my ability to write. I am further encouraged nowadays by technology that allows me to write even whilst driving, for instance, by speaking to gadgets and get it instantly transcribed. Writing is now not limited to using pencil and paper in the quiet corner of Hezekiah Oluwasanmi Library at the University of Ibadan!”

According to Adeyemi, the responsibility of a writer in theatre is to be a recorder and archivist. “Theatre is a living medium; writers are inly documenting what is happening. And we must be honest and conscientious,” Adeyemi explains.

He does not have any time of the day that he is comfortable writing. He believes the most difficult part of writing a book is when you’re starting. But he finds himself drawing more towards the witching hours of early mornings.

“The anjonnus are at their most generous then!” he laughs.

What literary pilgrimages has he embarked on in recent years?

Literary pilgrimages?” he laughs. “The ones I have always made – I read new works and re-read old works. I try to read works in their original languages (the few I could: Kiswahili, isiZulu, Yoruba, a smattering of Hausa). Last year, I worked with some new writers in Zimbabwe on a playwriting workshop. I am encouraged by their determination to write and perform in Shona and Ndebele. I am opening up my mind to Portuguese literature. And to the interest of the Chinese in our languages and literature!”

How long does it take him to write a book?

“How long is a piece of string?” he asks.

“I have a memoir – a creative response to Wole Soyinka’s Ake: The Years of Childhood, a bildungsroman – that I have been working on for more than 10 years, and yet I have a play that took me two weeks to write. The important factor is to never give up. And to share ideas with like-minded individuals; another benefit of being in AfTA,” Adeyemi says, adding, he learnt this “a long time ago from the Tuesday Poetry Club at the University of Ibadan, founded by the late Harry Garuba, and from the literary practices of Femi Osofisan, Bode Sowande, Olu Obafemi, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Samuel Kasule and the late Kole Omotoso.”

His grandmother Ajigbotola and great grandfather Atagbon of the Kiriji War fame are his heroes.

“My teachers – there are so many of them – writers all the way from antiquity, some of the writers mentioned above, my family, my friends, and Jahman Anikulapo!” he confesses.

If Adeyemi could live anywhere, where would it be?

“A compact, little orchard, with fruit trees and flowers, and a gentle stream flowing through it. With friends neighbouring. Anywhere in the world,” he says. He does not have anything to change about himself, except, perhaps, to be more compassionate. “Life is meaningless without compassion,” he says.