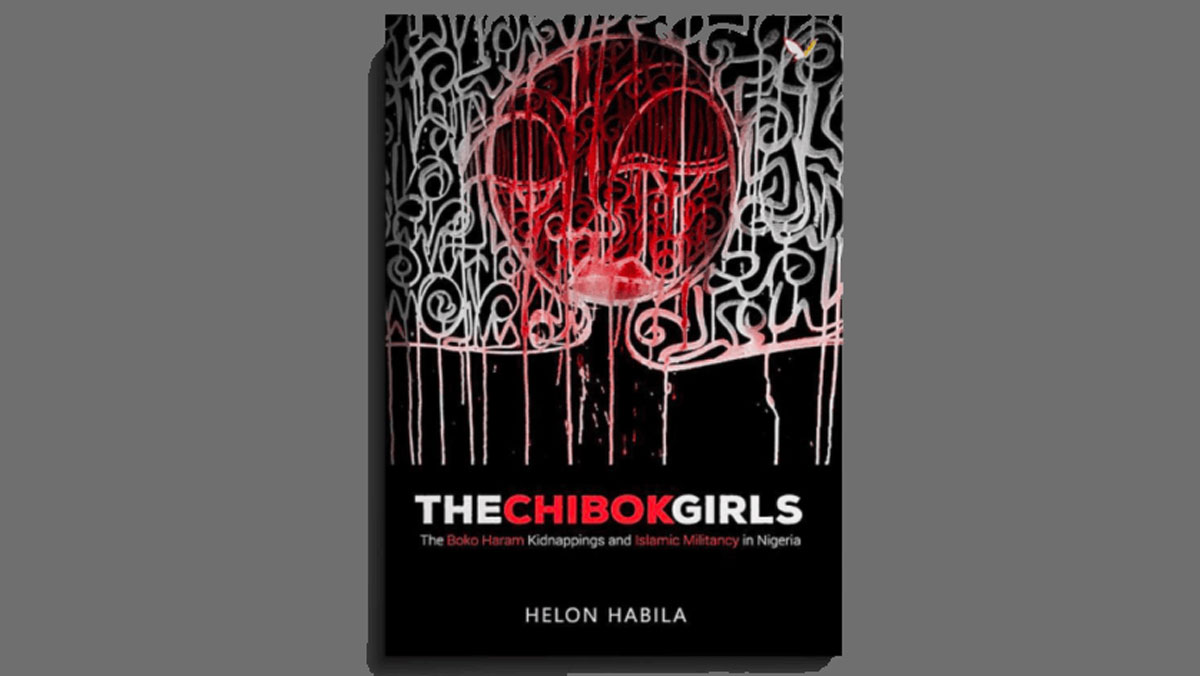

‘On the night of April 14, 2014, 276 girls from Chibok Secondary School in northern Nigeria were kidnapped by the deadly terrorist group Boko Haram. Fifty-seven of them escaped over the next few months, but most were never heard from again.’

This stunning blurb that opens the book, The Chibok Girls, introduces the reader to the “devastating account of a tragedy that stunned the world.” The Chibok Girls is a heart-rending account of a journey into the Boko Haram Heartland in the North Eastern state of Nigeria by Helon Habila, a great writer, and multiple award-winner, published by Parresia Publications Ltd.

The account of the author’s experience is made a lot more real, considering the fact that he was born in Gombe, a halfway point between Chibok and Maiduguri, the two hottest melting pots of the Boko Haram activities. The reader trails after the author, as a stranger after his guide, into an unknown territory.

Anyone familiar with the routes Habila takes would, together with the author, go through the harrowing experiences today’s journey offers. As the author begins his fact-finding mission to Chibok, where the girls were kidnapped, he reminds us of how it used to be at the police checkpoints before, and after the advent of the deadly sect.

In Chapter One, titled Professor Americana, the author captures “peace time” in Nigeria when policemen at the checkpoints would take bribes with a smile, reminding us of our ingrained corruption. He uses the technique of sarcasm, by referring to the ease by which they do so, as “all very civilized.” One can hardly miss the acidic humor. The author follows this immediately by the present situation. “Now the checkpoints were guarded by scowling, uncommunicative soldiers in full war gear.” This powerful description throws us into a war zone and the description of what happens at a checkpoint; the harrowing and often humiliating experiences at the hands of our military men.

As Habila moves to the affected areas by Boko Haram, he would often pause and give some background history of the dreaded sect, their early beginnings, who they are, what they supposedly stand for and the beginning of their terrorist activities. The early introduction does not only tell us who they are, but places the group in their exact geographical locations, an information not known to many Nigerians, not even to those living in the areas.

Habila also pauses in his movements to narrate events one would have heard in the media briefly. Events that had happened before the kidnapping of the Chibok girls, but which had not attracted that much public, or media attention, for instance, the invasion of a Federal Government College in the town of Buni Yadi, in Yobe State, February 25, 2014, where 59 boys were murdered in cold blood. It was an event that happened two months before the kidnap of the Chibok girls.

Chapter Two: The Day They Took the Girls is a sad account of that dreadful day the girls were taken. The author interviews a mother and the reader goes through the terror of that day as the mother recounts her day.

‘I was wearing only my wrapper. I managed to follow other people through the rocks under the hill, by the burial ground… and each time I heard the gunshots my stomach would turn and I had to go into the bush to defecate…’

‘She came back in the morning only to be told her daughter was one of those girls taken by Boko Haram. “I started screaming, and I felt as if my life would come out… I started running towards the school, screaming and running. I felt as if my world had ended. They met me on the way, and took me on a bike to the school. That was it. The girls were gone.” (emphasis mine)

These last two sentences summed up the entire story of the kidnapped girls and the story of all the parents of the kidnapped girls. There is nothing more to it.

In between narration, he retells the political history of Nigeria with its attendant crimes, religious violence, kidnappings and robberies. With rare insight, he analysis the Nigerian political situation in these courageous words:

‘Violence is symptom of a dysfunctional system, where people have no patience for or confidence in due process. The poor don’t believe they can get justice from the courts because usually they can’t, the elite know the system is rigged because they rigged it… Keep the people scared and hungry encourage them to occasionally pour their anger on each other through religiously sanctioned violence, and you can go on looting the treasury without interference.’

Again, the terror of the insurgency is recorded, without religious bias, when a young Chief Imam of Chibok recounts how his father, the older Chief Imam became a victim. On the day the dreaded sect sacked Chibok, the Chief Imam ran for his life, collapsed and died and was buried en route by his sons. Here the author attempts to enlighten the world, especially those who believe this is a religious war. The son who takes over his father’s position as Chief Imam cries out.

‘In Islam, any man who kills another man, with no just cause, he should also be killed… They now even kill other Muslims they throw bombs in mosques while people are praying. Islam does not sanction that. This is just a sect with its own doctrine and its own way of thinking, but it is not Islam.’

Part two treats ‘Inside Boko Haram Heartland,’ with Chapter Four titled Gombe, in Gombe State, is a casualty town because of the influx of Internally Displaced Persons, popularly called the IDPs, who fled their states, to take refuge in neighboring states. Again the Nigeria history is brought to the fore. Here the history of the Sokoto Caliphate that gave birth to the spread of Islam and the establishment of northern emirates, including the Gombe emirate is recounted. The author deftly wades into the challenges that confront the nation to date as a result of accident of history…

The region often seen by outsiders erroneously, as part of homogeneous “north”- meaning any part of the country above the River Niger – River Benue line and commonly viewed as all Muslim and all Hausa-Fulani- State has its fault lines. And because these divisions predated the birth of the nation, most people here- and this true to a large extent in other parts of the country- are always Muslim or Christian first, ethnic affiliation second, and Nigeria third.

Most of Chapter Four is devoted to Nigerian political and religious history, the chapters, demonstrates the writer’s ability in investigative journalism.

Chapter Five titled Maiduguri gives us the geographical description of the city. Again the author strives to unfold the genesis of the background history of the sect. Here he adds more information, some of which are not easily available, even in the media.

Alkali, a professor of creative writing, is the author of The Stillborn and The Virtuous Woman

‘Recently, a camp had been started to rehabilitate repentant Boko Haram fighters… About 800 fighters had already signed up, and there were plans to open more camps all over the northeast.’

Part three is ‘Return To Chibok’ with Chapter Six, ‘Waiting for the Girls.’ The author who has previously left Chibok without meeting with the escaped girls now returns to Chibok and in this chapter and chapter eight, we await the long anticipated meeting with the girls. For those of us familiar with the recent mode of travelling in the heartland of Boko Haram, the scenario is captured to the exact detail.

‘We were gathered on the outskirts of Maiduguri in a convoy of over 200 cars, trucks and buses. The road was still not 100 percent safe, it was right on the bridge of the Sambisa forest where Boko Haram was making its last stand, so cars could only travel with heavy military escort.’

Chapter Eight is ‘The Day They Took Us’ and concludes the story and takes up from Chapter Six, Waiting for the Girls. Back in Chibok, the author finally meets with two of the fifty six lucky girls who escaped. In their own words: “We jumped down (from the trucks) and started running into the bush. We ran for hours.”

That’s it. They ran for hours and reached home. The escape story remains consistent, the same story in both print and electronic media. The escaped girls are the closest link to the story of the kidnapping. From the fifty-seven kidnapped girls the author interviews two, and from approximately 219 families of the missing girls, he interviews one. That he chooses not to interview more parents of the missing girls or, just a couple of the escaped ones could have been as a result of the mystery of the entire phenomenon. 276 young girls from a federal government boarding school were neatly taken by a deadly terrorist group, and except for the fifty-seven who were lucky to escape, nothing is heard from the rest of them… Since then it has been a profoundly deep, dark and eerie silence…

The Chibok Girls is a narration that carries us along a torturous path of sheer terror. We share the pains of missing a child and empathize with the parents. The book awakens our consciousness to the gravity of the situation. It is my conviction that the narration about this devastating phenomenon has just began. For Nigerians, the International Community, Parents of the Girls and All of us concerned citizens of the world, Habila, a great writer and a multiple award winner would, for us, do a greater service by carrying on with this highly valuable research, until God in His Infinite Mercy delivers the 219 remaining girls from the clutches of the deadly sect. Then the world would come to know, for the world deserves to know, what actually happened to over two hundred vulnerable and innocent children on April 14, 2014.

* Zaynab Alkali is a professor of English and creative writing and a pioneering female novelist from Northern Nigeria