The name JOSY AJIBOYE brings memories of humorous, educative and entertaining cartoons to mind. Ajiboye’s works spoke volumes to the teaming audience that followed him over 29 years of his sojourn at the Daily Times. Although he has retired into a quiet life, he continues to paint, producing some of his best works yet. He spoke with FLORENCE UTOR on his career and life.

At what point did you become aware that you were art inclined and what was your parents’ reaction when they discovered you were going into the arts?

My case is very peculiar because I was born into a royal family. My father was a high chief. I grew up in the palace and, traditionally, artistic things like the poles in front of the doors, the doors and other artistic objects have always been there, but nobody saw it as anything serious. Although they were not in everybody’s home, but people didn’t see it as we see it now.

I didn’t even know it until I got to school. In my time, school was not important, though I come from Ekiti; this was around 1953, 1954. Then the headmasters from mission schools such as Anglican, CMS and others would go to the palaces of the obas everyday and beg them to send their children to school so that when the ordinary people saw it they would know that education was a good thing to do and they too would send theirs. After much persuasion, one day, my father just looked around and said, ‘ok, you can take that one.’ He thought they would be discouraged because I was still crawling on all fours.

This did not discourage the Catholic priest as he came everyday after school at 2pm to take me to their compound. In those days, all teachers lived in one compound, and he would just give me one small drum like that to be beating. I would do that until I slept off and then he would take me back home. That meant school \was over for me for that day. So, if we want to talk about when I began school, maybe I should say, that was when school began for me.

But you had older siblings. Why didn’t your father send those ones there, too?

People didn’t know the value of education back then. Why he even asked that I could follow the priest was just a way of telling him that ‘if you can’t give me peace, just take that one,’ which was me. It was just so that they would stop disturbing him. He wasn’t sending me because he understood.

As I grew, we began using the plank slate with chalk; then, in infant two, you would use slate with pencil. Thereafter, you go to Book One, where you begin to learn English.

Being an artist?

In fact, I never knew when I was not an artist. Once I learnt how to read and write ABC, both in English and Yoruba, it seemed like drawing. I have the same feeling. At the time, I had never seen anybody being an artist professionally. The thing is that every school I went, I was always the best artists or the artist there. At CMS Erimope, my town, African Bethel School, Ikorodu, I was doing chats like I did in every school. As I progressed, each time I displayed my works at home and the other chiefs came for their usual meetings, no matter how serious, they would first come and look at the works and they would show admiration and surprise. They would ask questions like, ‘are you the one who did this?’ I could draw all the masquerades in our town very well by heart. This really excited them. I guess they were just curious, but we had never heard of anybody making money from arts.

My father became very proud of what I had become and the way the other chiefs admired my works. Apart from that, I never heard of any art school or teacher teaching art until I got out of elementary school. Though woodcarving was quite common, like the Bamgboye’s from Kwara State were into it and they knew my father. They were the ones who used to make the cover for Ifa priest, beautifully decorated pieces and they were bringing in those art pieces to our palace and other places. So, art was not exactly new to them, but that someone did that for a living and doing nothing else was strange to them.

After the death of my parents – mother died in 1965 and father in 1966 – things were no longer the same and I had to look for a way of paying my tuition to attend school until I took\ GCE, which was the popular thing then. But as luck would have it, the Sudan Interior Mission (SIM) had so many outlets such as churches, radio, magazine, bookshops and other things and I started work with the magazine arm of the organisation from 1961 to 1968. I was employed as a trainee; so, the bulk of my training as an artist was from there.

When I got to SIM, now ECWA, they were impressed at what I could do, but made me realise that if I could do that much without training, I would do better with training and I did that for three years.

I had finished my training but as children, when you heard that someone went to Yaba College of Technology or university, you will be thinking that what they read there is different from what you know. So again, SIM gave me scholarship to go to Yaba Tech. At that time, they were only giving admission to people who were already professionals; it was advanced training and my teachers were Yusuf Grillo, Uche Okeke, Jubilee Owen and thereafter, I returned to SIM and finally resigned in 1968.

The mission didn’t like it that I resigned but since I felt I was not training to become a pastor or a missionary, I didn’t expect them to pay me as a full fledged artist coming out of the university. So, I decided to work for myself; they then gave me condition to work for them as freelance, doing my thing and still doing theirs.

How and when did you get to Daily Times, where you spent most of your working years and what was your experience there?

When you are working as freelancer, all manner of people will be coming to you to do different things for them and this was how I came across Daily Times. They were sending stuff to me to illustrate for them and many people saw these things. Somehow, the then Chairman and Managing Director, Babatunde Jose, noticed it too and invited me over. I didn’t even know where they were located; it was the person bringing illustrations, who took me there.

When I got there, the then editor, Sam, asked if I wanted to work for Daily Times and I said ‘no.’ He insisted I should see Jose. When I got to him, he just said, ‘you will work for Daily Times. He was telling me, not asking but I still declined. He was shocked because, about that time, anywhere you went you would see piles of applications. One Peter Obe, who came in and heard our conversation, just told Jose that ‘these SIM boys can be nasty o; they know exactly what they want and you can’t force them to do otherwise.’ Jose then asked me how much I earned in my last employment and I told him 16 pounds, 16 shillings and 8 pence, and I left.

A week later, I got employment with Daily Times and I was to be paid 60 pounds, with other incentives such as a car loan six months after I was confirmed a full staff.

The whole thing looked ridiculous to me. I was a very young boy then and the thought of owning a car was not something a fell for. I just thought over it and I decide to take the job, not for the money but to create an impression and to let people know whom I was. Even at that, I worked for a month and resigned after I collected my first salary. There was one Mr. Nwosisi, who was the administration head. He loved me so much just because I was an artist. He looked at me and asked, ‘please, tell me, is every artist a mad person?’ He drew open his drawer and showed me piles of applications, but I told him I was not looking for work.

Before I could get back to my office, the news had gotten to Jose and he was already summoning me to his office via my intercom. When I got there, three other directors were there waiting for me. As soon as I entered, Jose asked me to explain to the other people why I was resigning only after one month. He asked what I was going to tell the people outside that Daily Times did to me since I did not complain and did not have any complaint.

I was confused; I couldn’t say a word, but I think my reason was, I had never worked for a secular organisation. I was not just used to it; I was used to the mission’s way of doing things. For instance, if you go to the newsroom of any African press from 2pm you would think a riot is going on. To me that was disorderly. I couldn’t compare it with my eight years with the missions, where I got all the training that all the universities in this world put together could not give me.

When I talked about the disorderliness, one of the directors said, ‘Josy, I know what your problem is, that when he got to Daily Times, he felt the same way after he came back from a three-month training at the Mirror, the mother office in London. In fact, he was praying for the day of his return to Nigeria not to come.

He said the people at Mirror were so cautious. If they wanted to borrow your pen they would first take permission and when they were done, they would return it and thank you. But at Daily Times, they would just pick your pen as if it was theirs and when they were done with it, you will be the one chasing after them to collect it. That was the etiquette I was used to. Good enough, Jose understood everything and the only thing he said was, ‘if you respect me, you will withdraw that letter; that was how I spent 29 years of my life at Daily Times.

When I finally retired in 2000, it was Onukaba Adinoyi-Ojo, who was heading Daily Times and he said to me, ‘I hope you know that you cannot retire completely.’ So, on the day I should have got my retirement letter, I got two letters – one was my retirement and the other was a contract letter.

Again, I worked for another two years and finally left and began my paintings, which is the first thing I was doing even though people knew me as a cartoonist.

Was there ever a libel suit as a result of cartoons lampooning those in authorities?

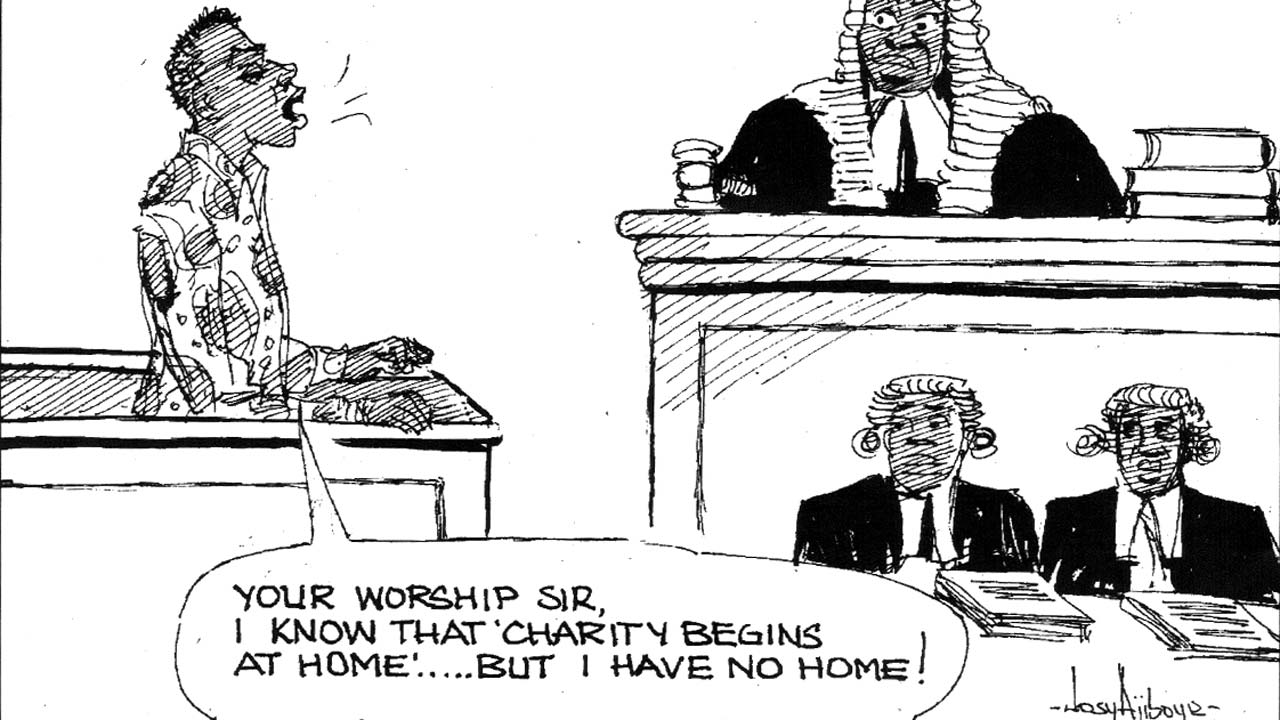

The type of cartoons I did were not like the type these junior boys do now, where they just read the headline and add their rider. No, that was not what I did because of the background I had. I added philosophy to my contents; I was also matured enough to know what I should draw and the way to illustrate it. These cartoons are from years back, but see the way you are laughing; this is the way anyone will still laugh at it 20 years later. I got to Daily Times as the assistant senior artist and later I was promoted to the art editor.

Do you feel fulfilled as an artist financially?

When you talk about arts, you don’t really talk about money because there is no real artist, who has remained in arts for the money. I am not talking of the music of these days. I am talking about those people who practice music for the love of it, the type that is evergreen, like Victor Olaiya, or Rex Cardinal Lawson. I can’t remember his real name; in those days, he used to play at Kakadu and I would trek there from Mushin to go and listen to the man. I didn’t even understand what he was saying until I read where he granted an interview and was explaining the meaning of those songs. But even before then, it made meaning to me. All that was knowledge; it was arts; it was everything unlike now that everything is money and as a result, Nigeria does not know peace again.

Imagine all the people into kidnapping and other crimes just because of money, what do they gain? The first time I was to illustrate cocaine; I was shocked because I didn’t even know what it was. I only knew cigarette. It is like talking of Prof. Wole Soyinka and his likes; you know that if Soyinka were like most people today, you would see his house everywhere, but around that time artists were just satisfied with what they were doing. Look at Onyeka Onywenu, highly educated and sophisticated, but these are people who did arts for the love of it.

There was one of my students, who was a policeman; he loved arts and just wanted to be trained. What he would do with it, he didn’t even know. Moses Olaiya and King Sunny Ade actually ran away from home, telling their mothers they were going to university, while they came to Lagos and were doing music; that is what arts is all about, satisfaction.

In the past, you see cinema houses everywhere. The likes of Hurbert Ogunde, Baba sala, Ade Love and the rest of them suffered to study art and bring it to the people. It was never all about the money; it was just to show the people what they could do.

When my son was going to Eko Boys High School, I warned him never to tell people I was his father. When he got to his art class and the teacher saw what he was doing, he felt it was beyond him and one day he asked him if I was his father and he couldn’t deny it. That day, the teacher accompanied him home to meet me in person just because he loved my works. I begged the teacher not to handle my son with kid gloves; that he should not spare him because he was the son of someone he admired; these are some of my gains.

There was a day I opened one of these magazines and I saw this actress standing by an expensive car she acquired and was showing it off, but you, who is looking at the car know that the money didn’t come from what she claims to be doing; we live in a funny society.

The thing is, no matter what, the people who will be artists, will be because all you want is to what makes you happy.

I may not have all the riches to match my popularity, but my children enjoyed the goodwill of people who only knew my works, but never met me in person.

In your view, do you think government has done enough to assist artists in their passion?

What I really think government should do is to create exhibition places. If this country were artistically civilized, the artists will be given their due. In Italy where this whole art thing began, the artists were made comfortable; that is why art was only for the royals. Here, all we ask for is simple: create galleries!

For instance, the National Council for Arts Culture (NCAC) should be open to anybody who has art works to display, weather you are still in the university or practicing already, so that when it is sold, the council will take their own percentage and give the artist his.

All your children are also artists, though they are working in other places. How did they pick the interest to follow in your footsteps?

When you send children to the university, I guess they will just want to see themselves among their peers, but they are all practicing arts. My two sons had an exhibition at Terra Kulture and my two daughters are hoping to hold another soon. Again, putting up a studio these days requires money. Before I put this place together, it cost money but I wanted a place that was big because I have students from ABU Zaria, Ife coming for internship. So, now I have a place that can accommodate a couple of people at a time, even those doing sculptor can have enough space to do their work.

Which of your exhibitions has been financially more rewarding?

I have been exhibiting since 1977, and I will say they have been rewarding except that when you want to exhibit in private studios, you are charged up to N200,000 per week. Let government have places where artist can exhibit their works like they were doing in the 1960s, when the white man was still around. NCAC exhibited my works recently and I was happy because if I wasn’t good enough, they wouldn’t have done that. Abroad, the people who sponsor exhibitions virtually take over everything, including publicity and even the guests to be invited. People even pay money to enter the exhibition venues; that is the difference.

Prof. Ekpo did a lot for artists, including Kolade Oshinowo. They exhibited artists a lot until people who didn’t know anything about the arts began to become director general of these institutions and everything died a natural death. Look at the National Theatre; it cannot even be renovated and put in proper condition for artists to have their performances there. I was reading where they said AMAA was billed to hold there, but it could not; that is a typical example of what I am talking about. Minister Edem Duke even wanted to sell it and this was where FESTAC took place; it is sad.

In colonial times, Glover Hall was the biggest place for performances; that is where the likes of Ogunde performed and they only took a percentage of what was realised at the shows. As far back as 1930 and now, things should be better, but look at where we are. If it was not for Ben Bruce, we probably would not even have a cinema; he brought it back before others followed suit.

Your cartoons made a lot of social statement. How did the powers that be react to it?

The way I did my cartoons, I didn’t talk about what I did not know or could not prove. The only time I had trouble was when I was to travel to London for training. We submitted our papers to immigration, but out of four of us only me was denied passport. Each time I went to ask for the passport, they would assure me it would come and after a while, I decided not to go there again.

I thought that even if I collected my travel papers, they would hide under something else to harass me. It was later I discovered it was all about a cartoon I had done immediately they decided President Shehu Shagari and Chief Obafemi Awolowo’s case. The way I did my cartoons was not a way you could come out and say it was a clear case of libel.

In this cartoon, I read where they said Awolowo must not be allowed to be minister otherwise the British people will have to stop getting anything from Nigeria. When they eventually gave it to Shagari, I did the cartoon. How the security understood it, I don’t know. I put the map of West Africa and at the spot where Nigeria is, I put a cat and its fangs caught a mice and it was dripping blood, and I wrote, Democracy Murdered Again.

I think the issue was, whoever got 13 states won the election, but none won it; so, it meant they were to go to electoral college. But the government knew that there was no way Shagari was going to be able to outdo Awlowo; it was also clear that the government wanted Shagari. So, instead of going to electoral college, they went to court and who owns the court?

My interpretation of that into a cartoon was that we said we were going back to democracy after many years of military rule, but democracy was murdered with that action.

So, when do you hope to retire from practice?

When I left SIM organisation, my intention was to start my painting like I was doing before Daily Times came. As a result, I will say I only did what people wanted me to do, not my first love, though I enjoyed it but now I can say I am doing exactly what I always wanted to do, and this cannot end till life itself ends.