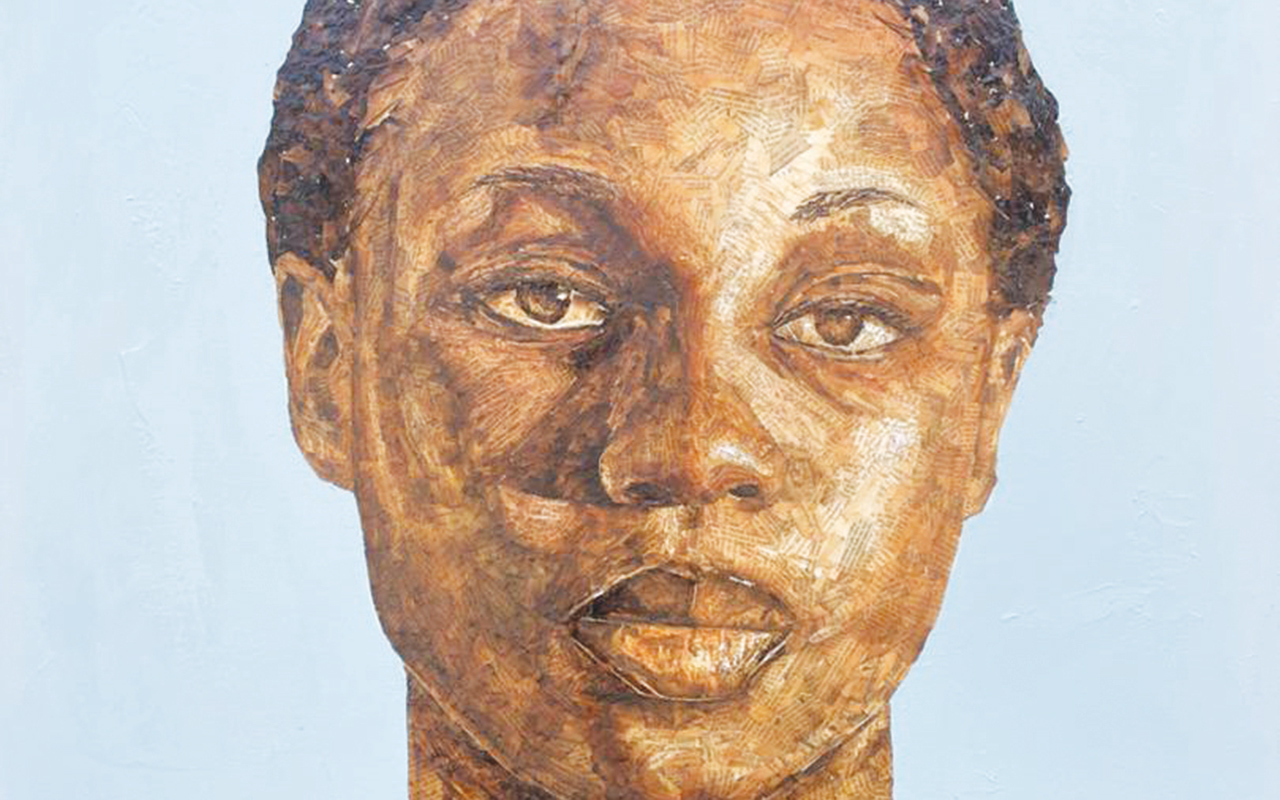

Noo Saro-Wiwa is the author of Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria (2012).This book was nominated for the Dolman Best Travel Book Award, and was named the Sunday Times Travel Book of the Year in 2012. It was selected as BBC Radio 4’s Book of the Week in 2012, and was nominated by the Financial Times as one of the best travel books of 2012. She was awarded the Miles Morland scholarship for non-fiction writing in 2015. She has contributed book reviews, travel, analysis and opinion articles for international media. In 2018, she was a judge for the Jhalak Prize for Book of the Year by a Writer of Colour. She speaks with OLATOUN GABI-WILLIAMS on books, family and the challenge of being Ken Saro-Wiwa’s daughter.

You were born in Port Harcourt to the legendary writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and Maria Saro-Wiwa; you were raised in the UK and have lived in the United States. Tell us something about your childhood. A bit about everything.

From Nigeria, we came over to England, when I was a toddler and my two elder brothers started boarding school in England. We lived in a regular house, went to the local primary school, and then we all went to different boarding schools around the country.

You lived in the United States, didn’t you?

That was just for one year. I did my master’s degree at the Columbia University, in 2001.

Which school in England did you go to?

My twin sister, Zina, and I went to Roedean, a boarding school in Sussex.

Did you discover your love of travel going home to Nigeria for the summer holidays?

I have always wanted to travel. My father took us to the U.S. when I was 10 years old. I was really excited. That was the first time we went anywhere that was not Nigeria. And because we always flew Alitalia to Nigeria, we once stopped in Italy during the athletics world championships. I was really excited. My father took us to the stadium. So, those were two holidays, back-to-back. They were the only non-Nigerian travel I did as a child – I was aged 10 and 11.

Do you think it was a fairly normal Nigerian upbringing?

No.

What was the distinguishing factor in your childhood?

In Nigeria, people thought and still think that we have money, but it wasn’t and isn’t like that. It was a very weird upbringing. We attended these posh boarding schools because education was my father’s priority, but with five children that’s where the money went. So when you looked at where we lived, and the presents we got at Christmas and all that stuff, it was very ordinary for us, not a rich kid’s experience. We had less than the average child in our peer group.

When it came to clothes, when I needed extra, I would I borrow my brother’s. We weren’t like the Lagos set. Many of the Nigerian girls at Roedean came from rich families. A lot of them lived in Ikoyi and Victoria Island. That’s where they went every holiday. But when we went back in the summer it was never to Lagos. We lived in Port Harcourt. My father was a property developer in the 70s. He rented out some places, but we lived in a modest house right at the edge of town. Everything we did was totally different. We’ve always occupied a strange space. Even when it came to cars: everyone drove Peugeot 504s but my father drove a Toyota Crown.

You’ve made it clear: economically you were not on top but intellectually, your family has always been highly esteemed. You are well-known as at travel writer. Your sister, Zina, is a well-known filmmaker. I believe she describes herself as ‘alt-Nollywood’? Your late bother, Ken Jr. and your father were both celebrated writers. Coming of age, were you conscious of your artistic and intellectual heritage? Were you consciously following that path or did you just find yourself falling into writing?

While we were growing up, it was: just do what you want. Initially, when I was around 10 years old, I thought I had to be a doctor, because that was what my parents wanted. But they just wanted us to do well. I think because we never saw my father work for anybody – he was always self-made, always his own boss – we grew up with that mentality. You don’t go off into a corporate job, or whatever. You think, I’ll try and make it in my own way. Many people have that ambition but because they don’t have a role model like our father, they have less sense of it being doable. They just dream about it. In particular, my sister and I always pursued what we wanted. But it comes with sacrifice: you’re never financially stable or secure, but there is no alternative. The alternative would be just to sit in an ordinary job.

Tell us more about your father, his background and what made him special.

He grew up in this poor family, in a typical village in Nigeria. His mother was a farmer and my grandfather was a forest ranger, initially. Then he began selling minerals (soft drinks) in Bori, a small town in Rivers State, where my father was born. Because my father was bright, he won a scholarship to Government College, Umuahia. That was his way out. He was very ambitious, and didn’t put limitations on anyone. He always told us you must never limit yourself.

After Umuahia, my father attended University College Ibadan (now University of Ibadan) and then he taught at University of Nsukka. He was a lecturer in English, I think, but not for long. He married my mother around that time, and then the Biafran War broke out. When he became a commissioner on the Nigerian side, he and my mother escaped to Lagos, which is where my oldest brother, (late Ken Jr.) was born. My parents returned to Port Harcourt after the war ended.

He was known as a quiet man, but public perception of a man can be very different from the perception of those around him in his private life.

Yes, he could be moody and quiet when he was writing. It’s difficult to describe…your parents are going through stuff, you are a child, you don’t know what’s going on. So looking back, I see that he was sometimes stressed about this, that or the other, but I couldn’t tell you what about. Then at other times he was completely the opposite: loud and laughing. He was a bit of mix.

Were you aware when he started getting active with the Ogoni cause? How organised was it all?

He gave us his pamphlets and copies to read, when I was 11 years old or so. When we drove to the village he would point out the gas flares and say, look at this. When you’re a child you don’t pay much attention to that stuff. In Port Harcourt, lots of people were members of the Shell recreation club. It had a swimming pool, tennis court and a library.

I remember my father stopped going there, but he gave us his old membership card from the 70s. My sister, me and my little brother (who died in 1993) would go there and they would let us in. But around 1989-90, I remember my father became reluctant about letting us go to the club. But he relented because it was the only entertainment we kids had.

The judicial murder of the Ogoni 9 was breaking news across the globe. After your father’s death you decided you wanted nothing more to do with Nigeria. But you did return.

Well, we returned twice for his official funeral in 2000 and for his real funeral in 2005. When you say ‘official funeral’, what do you mean?

We did not have his remains for the first, official funeral. The Sani Abacha government dumped them somewhere. So we had an official funeral, involving the whole village. Ken Jr. (my late older brother), and my uncle Owens, worked with Obasanjo to locate my father’s remains and have them identified forensically. We didn’t get the remains until 2005. Then we held his real funeral. The second burial was immediate family members, including my uncle and my half siblings. So it was just those two brief trips back to Nigeria.

Your father, Ken Saro-Wiwa, was also a pro-democracy activist. He was one of those to whom author, Abraham Oshoko, dedicated his twin graphic novels (The Declaration and The Annulment) about June 12’, that pivotal moment in Nigeria’s history. Share your thoughts about June 12 as Nigeria’s official Democracy Day? And then tell us how you feel about the presumptive winner of the 1993 elections, MKO Abiola, having the title Grand Commander of the Federal Republic, a (GCFR), title reserved for presidents, conferred on him by President Muhammadu Buhari.

Well, it doesn’t reflect the true confusion in the country. Abiola is dead. If he were alive today and running for president, would Buhari be doing this? It’s easy to be nice to people that are gone. These are all superficial things. When leaders care about the country they make real changes that affect ordinary people. None of these declarations are going to help someone who has mouths to feed, who does not know when they will next be paid. People want substantive change.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time in China. That’s what my next book is about. People try to draw a parallel between China and Africa but they are very different. The Chinese government has a strong sense of identity: their history goes way back. They can’t stand the fact that the West has dominated the world over the last few centuries. They want to reclaim their position. They feel they can compete with the West and do things better than them. Yes, the government is dictatorial and commits terrible human rights abuses, but it also wants to pull people out of poverty. It has a target to lift 45 million people out of poverty over the next few years. You can see that the standard of living is rising. It may not be able to rise forever but right now it is happening because their government is actively trying to make it happen. But in Nigeria, many of our politicians aren’t embarrassed by the state of affairs in the country.

What did you study at university and how did your life as an independent explorer begin?

I studied Geography. My travelling life began when I won a Rough Guides competition, which involved writing an essay on a city. I had already spent a summer in South Africa doing a dissertation for my degree, when I was 20 years old, so, I wrote an essay about Johannesburg and won the competition. The Rough Guides West Africa editor said the winner could go anywhere in the world. I was so excited. I wanted to go to South America or the South Pacific. But then he told me they needed someone to update the guides to Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea. I was disappointed at first but I agreed to go. So, I went backpacking around these two countries. It was a life-changing trip. They are francophone countries. Initially, I was quite scared but I learnt to speak some French, and people out there were often helpful because I was by myself. There was no internet those days: you had to personally inspect the hotel rooms, describe them, get the price, go the national forest reserves, find out entry fees, check out restaurants. I couldn’t do that now. I had much more energy then.

Did that lead you directly to Nigeria?

No, not directly, but it triggered my interest in Nigerian travel. After Rough Guides I worked for ABC News (American TV network) as a researcher and production assistant at their London office. That was my first proper job after university. I then went to Columbia University in New York for one year, then returned to ABC for another 18 months before leaving for South Africa.

By then I was about 26 years old. It was while at Columbia that I realised I didn’t want to be a reporter. I liked writing about everyday stories, everyday people; things that didn’t necessarily have hard news value but told you something about the society. That was when I decided to write a book about my travels in South Africa. But just before I left for Johannesburg (I’d saved up money), I came across an advert looking for writers for the Lonely Planet travel guides. I couldn’t resist so I applied. They liked my writing and asked me to cover Madagascar, Ghana, Togo and Benin for the Africa on a Shoestring series. I also went on my own personal trips to Senegal, Sao Tome, Gabon. By the age of 28 I had travelled to about 10 countries in Africa either as a tourist or as a writer of guidebooks.

Around that time, the idea of travelling around Nigeria began to appeal to me. But I didn’t want to just go back to Port Harcourt or the village, as it reminded me of my father’s death. I wanted to travel around like a tourist, the way I did in the other countries, and write a book about it. Suddenly, it all came together. The idea of travelling without family and being anonymous excited me.

Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria is your first book. Chronicling your fascinating journey across Nigeria, it was published to critical acclaim in the UK. For example, in 2012, it was listed by The Guardian (UK) as one of the 10 Best Contemporary Books on Africa. It has been translated into Italian and French and won the Italian Albatros Travel Literature Prize. Share one of the most memorable experiences on your travels around Nigeria.

Seeing the gorillas and chimpanzees in Obudu Cattle Ranch in Cross River State. I didn’t know Nigeria had all that.

When you think chimpanzees, you think Gabon, Congo and Central Africa. But Nigeria has them too, and that’s incredible.

I really love apes. They share 98 per cent of our DNA. When you interact with them, they are so human. And they are seriously endangered. There are about 200,000 chimpanzees left, in isolated pockets. And the Obudu Ranch is just a five-hour drive from Port Harcourt. People don’t really appreciate it. An American woman runs it. She has difficulty getting funding from wealthy Nigerians so she relies on the international community. And that’s the one thing that would really bring people to Nigeria: chimpanzees and gorillas. We have such great assets but we don’t appreciate them.

You write glowingly about the work being done on the farms you visited in Kwara State. Tell us about your experience with the Zimbabwean farmers in Kwara and about how they got to Kwara State in the first place.

President Robert Mugabe kicked them out of their farms, and the former governor of Kwara State, Bukola Saraki, invited them to settle in Nigeria and use their expertise here. I was impressed that the governor had tried to do something. Obviously with Zimbabwean farmers, you are not going to get a deep conversation with them. Our discussions were business-like. They are not going to tell you their real thoughts, necessarily. But it was a fascinating visit. The Fulani were encouraged to bring milk from their cows and sell them on these farms, which benefitted them financially. I don’t know what became of those farmers or whether their project was ultimately successful. They leased the land, they don’t own it. Obviously you have people from the diaspora coming back and setting up businesses, but this state-sponsored invitation to foreign farmers was quite unusual at the time.

According to conventional wisdom, Africans are not explorers. Your thoughts about this?

There is some truth to it. Travelling (for the sake of it) is more of a Western thing, although you had people like Tété-Michel Kpomassie who travelled to Greenland in the 1960s. My father was very open-minded and open to new influences and encouraged me and my siblings not to feel restricted. We applied that principle. Many Nigerians are the same. We’re great like that: we’ll settle anywhere and make ourselves at home. I know of someone who grew up in a Nigerian community in Alaska. If the door to Buckingham Palace were open, we’d stroll right in!

People talk about role models; they say you need people like you in order to be inspired to do things. I never felt that way. If I saw some white guy climbing Mount Everest, I still thought I could do that. My family has always had that mentality. That is why travel writers inspired me even though they were white and/or male. I wanted to do what they were doing but in my own way.

How do you think travel writing should be approached? Creatively? You know, fiction mixed in with the facts for the sake of impact?

No, I’m all about non-fiction. Sometimes you have to change a few small facts in order to protect someone’s identity. There was a point in Transwonderland when I had to hide a woman’s identity. She was from the Middle Belt and adamant that the Hausas should not over-represent themselves when registering for elections. By the time my book was published, Boko Haram had kicked off and there was more violence in the region. I thought if I revealed her identity it might cause problems for her since she works in an easily identifiable place in Jos. So, in the book I pretended she was light-skinned, and I hid her job description.

But for me those are minor details. I would not change the location of the conversation or invent things that she said. And that’s the problem. People ask if I have ever embellished my stories.

What do they mean when they ask you whether you embellish?

You know, Nigeria is such a crazy place. Westerners who haven’t been there might find it hard to believe the things that go on. I get frustrated because there are travel writers who have twisted the truth and created cynicism amongst some readers. They wonder whether you have done the same. I get quite annoyed by that. For me it’s important to be faithful to the truth.

Somewhere in your book you said that your ethnic minority status in Nigeria grew almost as strong as your identity as a racial minority in England.

Yes, when you are in England the general population does not distinguish between the different Nigerian ethnic groups. When you are in Nigeria, you are aware that each region has a dominant ethnicity and language. When people ask you your name, they don’t know where it is from. Port Harcourt is the only place where they don’t ask me that question.

When my brother Ken Jr worked at Aso Rock, I visited his office and was shocked at how shabby it was. The main buildings are beautiful but my brother’s office had sagging ceilings because his budget was small. He told me the budget came from the Rivers State government. What did Rivers State have to do with it? I didn’t understand – he was the assistant adviser to the vice president, so, I assumed the Federal Government paid him. But he explained to me that everyone’s salary is paid by the government of the state where your ethnic group comes from. That surprised me. You realise how big a role ethnicity plays in everything.

So you felt alienated.

I felt more foreign. In the UK we’re all just ‘Nigerians’. But when you’re in Nigeria, you are more aware of the ethnic differences, especially in Northern Nigeria where the dominant religion is also different. You’re not Muslim, you’re not Igbo, etc. You wonder about the implications. In England, if you have enough money, you can buy a second home anywhere in the country. But in Nigeria can you just go to a village in the opposite corner of the country and buy a property with a nice river view, with Edo or Hausa people around you? There’s a stronger sense of being on someone else’s land.

We know that the political victories of Brexit in the UK and Donald Trump in the US were fuelled by the anti- (mass) immigration sentiment that has swept across the Western world. President Trump has called it ‘a movement’. Talk to us about A Place of Refuge, the anthology you contributed to, which was published by Unbound.

The editor of A Place of Refuge, Lucy Popescu, is the daughter of Romanian refugees and she wanted to produce an anthology that tells positive stories about asylum seekers to challenge the negative press about them.

My entry was an essay called, A Time to Lie. It was inspired by a visit to Italy. A woman I met there told me her husband had written an academic paper about why refugees might lie to authorities on their reasons for seeking asylum. It was a very interesting paper.

What was it about?

For example, a girl has been raped by insurgents in Mali. She goes to the police station but the police don’t take down the details since their bureaucracy is disorganised. Instead they ask her when she was born. She does not know because she was born in a rural area that doesn’t formally register births. She flees to Europe, arriving there without documentation and no police report about the rape. So she might pretend that her caesarean scar is a stab scar – whatever it takes to help her get asylum. The immigration officer suspects that she’s lying and rejects her application. The criteria for ‘deserving’ refugees are often dictated by the news agenda. So, someone from Mali might suffer just as much, yet they can’t understand why their application is rejected while a Syrian person is considered a legitimate refugee.

You’ve recently been awarded a prestigious Bellagio Residency by the Rockefeller Foundation. A cause for celebration.

Talk to us about that.

I wasn’t even thinking about applying for the residency but then the writer Yewande Omotoso (our fathers were good friends) encouraged me out of the blue to apply for it.

What was the application like?

You tell them about your career to date and your upcoming projects. My current project is about Africans in China. My next project will be my travels in the Niger Delta. The Bellagio Residency programme seeks to generate social change in various ways, so you outline what you are going to write about and how you can contribute to social issues through your project. At Bellagio, you get to mix with people from other disciplines. That’s what attracted me the most. It is a very serious programme in that you’re expected to knuckle down and work in a quiet, almost monastic, environment. I was hoping I might do some sightseeing, visit surrounding villages but they told me breakfast finishes at 9am, then we work!

[ad unit=2]