Ngugi wa Thiong’o falls into the first category because his works have not been given full recognition by any major international prize. His stature is so huge many believe it is a disservice to continue to ignore him for the Nobel Prize.

Indeed, on the African continent, many have agonised over how he has been overlooked in the last five years or more. So when Abdulrazak Gurnah was announced last Thursday, many were stunned that yet again the Swedish Academy has overlooked Ngugi for this year’s prize for an unknown African writer.

Gurnah’s name does not ring a bell on the African literary firmament, but with the prize throwing him up now, his towering literary profile has begun to emerge to stop those who would have begrudged him his elevated place in the pantheon of Nobel laureate like they did music legend, Bob Dylan, a few years ago when the Swedish Academy broke all conventions and awarded him the Nobel Prize for his outstanding lyrical achievement it viewed as being comparable to any literature.

Gurnah is the first Tanzanian writer to win. Of course, the last black African writer to win the Nobel Prize was Wole Soyinka in 1986 while Gurnah is the first black writer to win since the late Toni Morrison in 1993.

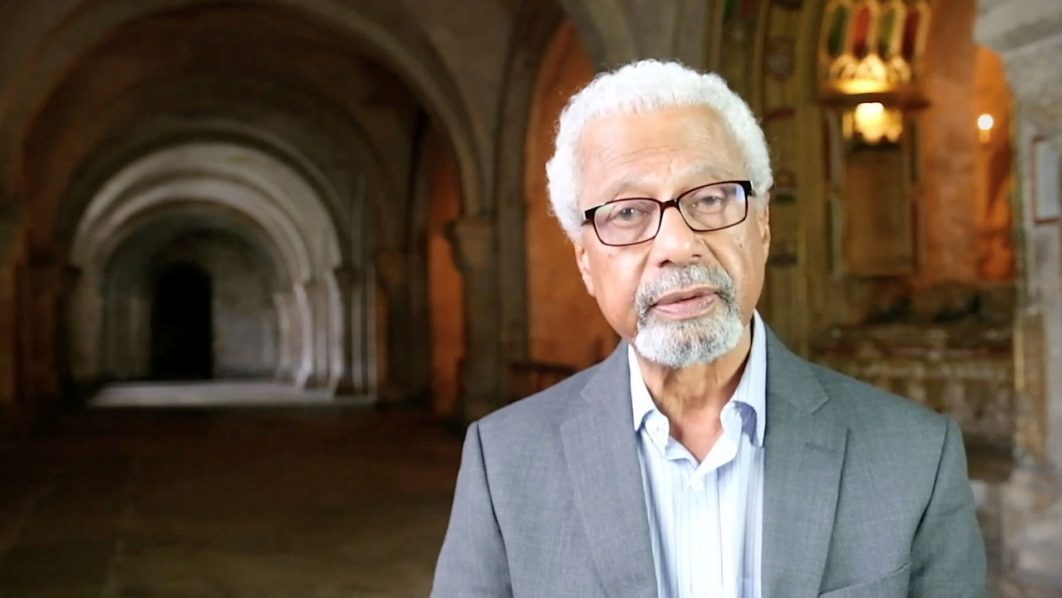

Gurnah was born in 1948 and grew up on the island of Zanzibar in the Indian Ocean but arrived in England as a refugee toward the end of the 1960s. After the peaceful liberation from British colonial rule in December 1963, Zanzibar went through a revolution, which under President Abeid Karume’s regime, led to oppression and persecution of citizens of Arab origin, with massacres being the daily fare.

Though Kiswahili is his first language, Gurnah, who lives and works in the U.K., writes in English. He was born in Zanzibar, the semi-autonomous island off the East African coast, and studied at Christchurch College, Canterbury, in 1968. It was not until 1984 that it was possible for him to return to Zanzibar to see his father shortly before the old man’s death. Gurnah has until his recent retirement been Professor of English and Postcolonial Literatures at the University of Kent in Canterbury, focusing principally on writers such as Wole Soyinka, Ngugiĩ wa Thiong’o and Salman Rushdie.

in 1987, he published his first novel Memory of Departure. His works ask critical questions about such ideas as belonging, colonialism, displacement, memory and migration. His novel, Paradise, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1994. It is set in colonial East Africa during the first world war. His works focus mainly on the East African Indian community and their interaction with the “others”.

Gurnah’s novel Paradise employs multi-ethnicity and multiculturalism on the shores of the Indian Ocean from the perspective of the Swahili elite. Gurnah is a distinguished academic and critic, who sits on the board of the Mabati Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African literature. He has served as contributing editor for the literary magazine Wasafiri.

He is currently Professor Emeritus of English and Postcolonial Literatures at the University of Kent, having retired in 2017.

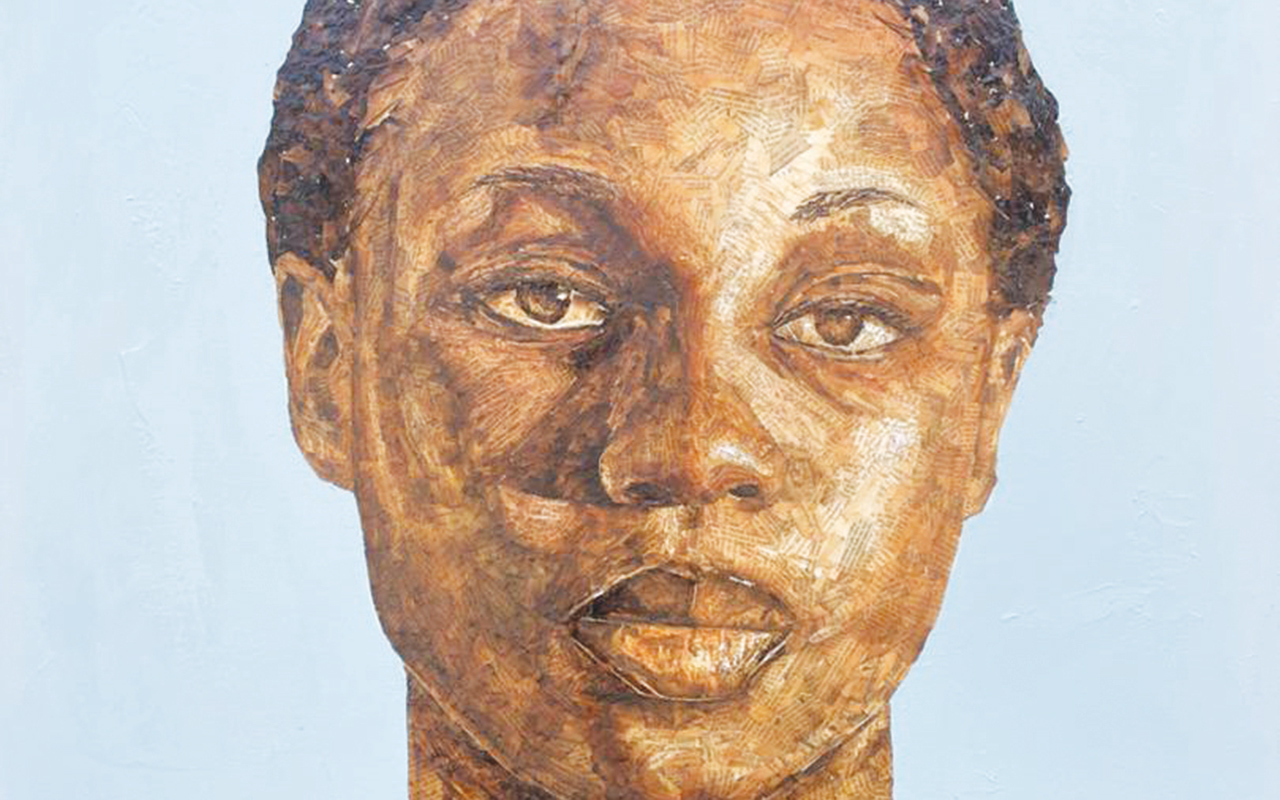

Literary pundits are agreed Gurnah was awarded the Nobel Prize for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fates of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents. He is one of the most important contemporary postcolonial novelists writing in Britain today and is the first black African writer to win the prize since Wole Soyinka in 1986. Gurnah is also the first Tanzanian writer to win.

His most recent novel, Afterlives, is about a man, who was taken from his parents by German colonial troops as a boy and returns to his village after years of fighting against his own people. The power in Gurnah’s writing lies in this ability to complicate the divisions of enemies and friends, and excavate hidden histories, revealing the shifting nature of identity and experience.

Gurnah has published 10 novels and a number of short stories. The theme of the refugee’s disruption runs throughout his work. He has said that in Zanzibar, his access to literature in Swahili was virtually nil and his earliest writing could not strictly be counted as literature. Arabic and Persian poetry, especially The Arabian Nights, were an early and significant wellspring for him, as were the Quran’s surahs. But the English-language tradition, from Shakespeare to V. S. Naipaul, would especially mark his work.

However, he consciously breaks with convention, upending the colonial perspective to highlight that of the indigenous populations. Thus, his novel Desertion (2005) about a love affair becomes a blunt contradiction to what he has called “the imperial romance”, where a conventionally European hero returns home from romantic escapades abroad, upon which the story reaches its inevitable, tragic resolution. In Gurnah, the tale continues on African soil and never actually ends.

In Gurnah’s treatment of the refugee experience, the focus is on identity and self-image, apparent not least in Admiring Silence (1996) and By the Sea (2001). In both these first-person novels, silence is presented as the refugee’s strategy to shield his identity from racism and prejudice, but also as a means of avoiding a collision between past and present, producing disappointment and disastrous self-deception.

Gurnah’s dedication to truth and his aversion to simplification is striking. This can make him bleak and uncompromising. At the same time, he follows the fates of individuals with great compassion and unbending commitment. His novels recoil from stereotypical descriptions and open our gaze to a culturally diversified East Africa unfamiliar to many in other parts of the world. In Gurnah’s literary universe, everything is shifting – memories, names, identities. This is probably because his project cannot reach completion in any definitive sense. An unending exploration driven by intellectual passion is present in all his books, and equally prominent now, in Afterlives (2020), as when he began writing as a 21-year-old refugee.

The novel Paradise stands out because Gurnah re-maps Polish-British writer Joseph Conrad’s 19th-century journey to the Heart of darkness from an East African position going westwards. In his fictional transaction with Heart of Darkness, Gurnah shows in Paradise that the corruption of trade into subjection and enslavement pre-dates European colonisation, and that in East Africa servitude and slavery have always been woven into the social fabric.

Like Achebe and what he did with Things Fall Apart (1958), Gurnah aptly shows East African society on the verge of huge change, hinting that colonialism accelerated this process but did not initiate it.

While the continent celebrates one of her sons for bringing home this prestigious prize to swell the number of African winners of the Nobel Prize, it is also African writers wish that Ngugi should clinch it as soon as possible judging from his high ranking this year.