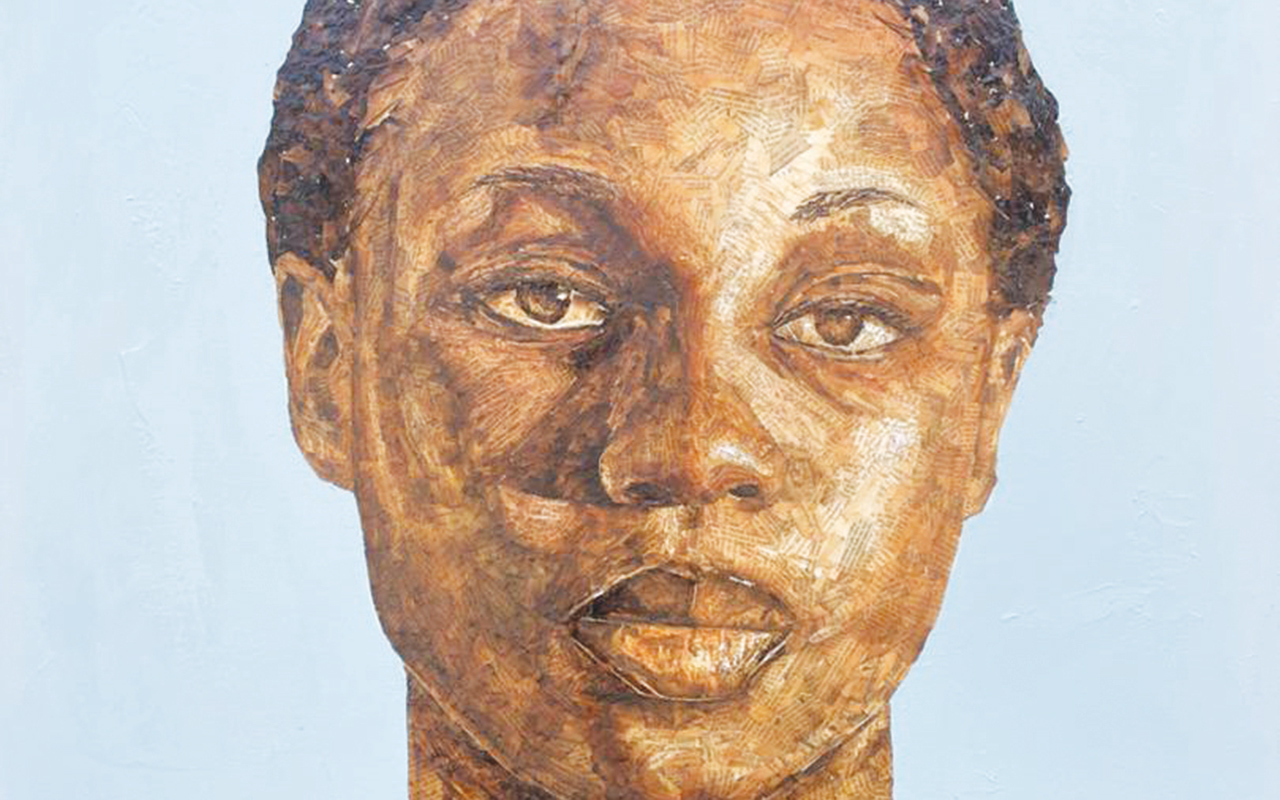

Henry Akubuiro is a journalist and creative writer, whose play, Yamtarawala, the Warrior King, has been longlisted for the Nigeria Prize for Literature sponsored by the Nigerian Liquefied Natural Gas. A novelist, playwright, short story writer, poet and biographer, he is the author of prose narratives –Prodigals in Paradise, Vershima and the Missing Cow, Adventures of Bingo and Bomboi and Little Wizard of Okokomaiko. Winner of many awards, including the BBC World Service Young Reporters’ Competition, National Essay Competition organised by the Federal Ministry of Youth and Sports, ANA Literary Journalist of the Year, ANA/Lantern Books Prose Prize, among others, he is also the Jury Chair of the 2023 James Currey Prize for African Literature and the Assistant Editor of Saturday Sun.

Congrats on being longlisted for the Nigeria Prize for Literature, what does this mean to you?

AS you know, the Nigeria Prize for Literature sponsored by the Nigerian Liquefied Natural Gas is the biggest literary prize in Africa and one of the most prestigious prizes in the world. Of course, Nigeria is the powerhouse of African literature, right from the Soyinka-Achebe era to the present generation when the Chimamandas are holding the baton. So, to be longlisted in a competition that attracted over 140 entries in a country like Nigeria is a big boost for one’s writing. It shows you are moving in the right direction.

Tell us about your play that made the long list, Yamtarawa, the Warrior King. That name is a tongue twister for some of us.

The name comes from the Northeast, where the play is set. Yamtarawala, the Warrior King is a historical drama centred around a larger than life king named Yamtarawala, whose father was the former king of Ngazargamu, the capital of Kanem Bornu Empire. The play revisits the crisis of succession in Ngazargamu following the king’s death. Unfortunately, Yamtarawala lost out to his younger brother, Umar. He felt hard done by as the older son and led 72 people to begin a conquest of territories southward, before establishing his own kingdom, the Kingdom of Biu, in southern Borno, which today, is the second largest emirate in Borno State. However, his conquest went with benumbing intrigues and power plays, which are part of flavours of this historical play.

Beyond the unique storyline, how socially relevant is this play?

I came across this story when I read the book, A History of Biu, which I consider a masterpiece, by Dr. Bukar Usman, the President of Nigerian Folklore Society, and I instantly saw an epic drama in it. Surprisingly, nobody saw what I saw. Again, that era hasn’t been well captured in Nigerian literature. Kanem-Bornu was a formidable empire while it held sway, one of the greatest African empires alongside Songhai, Mali, Ethiopia, Oyo, Benin, Ghana, Ethiopia, etcetera. It comprised the present Northeast region of Nigeria, almost all parts of Chad, northern Cameroun, southern Libya and southeastern part of Niger Republic.

Over the years, we have been campaigning on the need to bring back history to the school curriculum. This play does that in a dramatic way. The other day, I was watching Big Brother Naija, and I was totally flummoxed, because the housemates, in their 20s and 30s, couldn’t tell when the Nigerian civil war started. One ignorantly answered that Cameroun belonged to the Economic Community Of West African States (ECOWAS). Another couldn’t tell the capital of Bayelsa State, which was created in 1996, just 27 years ago. So, Nigeria, the giant Africa, is now breeding ignoramuses? This is unacceptable.

Besides, there is a whole lot of misconception about Northern Nigeria, especially from some of us in the south. Many of us don’t know much about the people over there. That’s why we have prejudices. Likewise, there are many in the north who are prejudiced against people down south, because they don’t know much about them.

The ancient Hausa civilisation might have fared a bit better in Nigerian literature because of, maybe, numbers; but the same can’t be said of the Northeast. If you reel out the greatest plays in Nigerian literature, the majority of them will definitely come from the southern part of the country. That imbalance stares you in the face everyday. It’s not as if this part of Nigeria isn’t a fertile ground for drama. I think our writers don’t fully appreciate the abundant materials waiting to be tapped from that part of the country.

When Abubakar Adam wrote A Season of Crimson Blossom, set in the North, you could see how it caught fire instantly. That was partly because that setting and the hidden gems in it hardly feature in popular Nigerian literature. They have to be unspooled.

So, I decided to take the bull by the horn and celebrate something unique from other cultures –Kanem-Bornu Empire and its sister domain, Biu Kingdom. It’s part of our responsibilities as writers to tell untold stories, no matter where they come from.

Lest we forget, Prof Ola Rotimi, a Yoruba, wrote the titillating play, Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, a Bini story. Today, it’s an African classic. If you also look at what Prof Wole Soyinka has done with history in Death and the King’s Horseman, you don’t need to be told that historical plays hold a candle to enduring literature, even ethnology. You are talking about a past we didn’t experience ourselves but that contained charms and dynamics that have impacted our existence.

Look at what J.P. Clark did with Ozidi saga from Izon legend, that’s fantastic! The personage, Yamtarawala, in Bura/Babur culture of Borno State, is akin to Oduduwa in Yoruba civilisation in terms of founding an ethnic group and Queen Moremi in the same culture in terms of valour. He is also comparable to Queen Amina of Zazzau in terms of being a revered warrior. Interestingly, Queen Amina was born in 1533 and ruled in the mid 16th century. She was only two years when King Yamtarawala, who had led a fierce military campaign from Ngazargamu, landed in the Biu area and founded the Kingdom of Biu, which is still vibrant today as an emirate with tentacles in Gombe and Adamawa. The Bura-Barbu people of Borno also see Yamtarawala in the same light as King Shaka Zulu of Zululand in terms of warriorism and the legendary Mansa Musa of Mali Empire.

All these personages I mentioned have features in Nigerian and African literature, especially drama, but nobody is talking about Yamtarawala.

People like Yamtarawala, who founded a very strategic ethnic group in the Northeast, nay in Nigeria, are authentic nation builders. Their generation and those before or after them were the first set of nation-builders we can boast of. So, the concept of nation building applies to this historical play.

The play is also relevant in terms of conflict resolution. For instance, when Yamtarawala fell out of favour with Ngazargamu and the new king, Umar, instead of fighting him, he went his own way in search of a new kingdom to rule, which he eventually got.

Yamtarawala is a national hero, no doubt, just like Igodo, the first Ogiso of Igodomigodo, of what was to become the Benin Kingdom. I bet you, most Nigerians haven’t heard about Yamta the Great, because history is almost lost to people of this generation. A play like Yamtarawala, the Warrior King, is key to reviving our history. Don’t forget, the play is also an epic performance deliberately written to ignite the stage by introducing something new and robust to Nigerian theatre.

This civilisation you mentioned in the play, did it occur before the coming of the British to Northern Nigeria?

Yes. This is an important history. Northern Nigeria suffered two types of colonisation: the Arab and the British. Those of us in the south only suffered one –the British. If you read Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God or Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman, this is evident. You will find, among others, a clash of cultures between the Christian religion and traditional religion.

In Yamtarawala, the Warrior King, I went back in time to the 16th century to depict that zeitgeist. There is a clash of cultures in the play, too. The play also explores the relationships between ancient North African and South Asian civilisations contemporaneous to the Yamtarawala’s era. I think contemporary Nigerian literature hasn’t done justice to that era. This is why I say this play is groundbreaking. The culture depicted here, the dances and language, props and costumes aren’t what we are used to seeing in Nigerian theatre and cinema. It’s totally a ‘new’, mind blowing theatrical experience. We must celebrate the Nigerian diversity as writers. Already, somebody is talking with my publisher for the movie rights. Quite amazing.

What went into the research since you are not from the Northeast?

This reminds me of what the greatest playwright of all time, William Shakespeare, did with the Roman plays. He was Scottish, but he wrote the popular Roman plays –Julius Caesar, The Tragedy of Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus and Titus Andronicus. These plays were written in the 16th century or so. Today, we are still studying them as literature texts in schools all over the world. That’s what great history does to literature. There has always been an affinity between literature and history. Let’s not forget also the Shakespearean classic, Macbeth, predicated on the reign of King Duncan IV of Scotland, or King Lear woven around kingship. These plays are still relevant till date. What about Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot, a play informed by a 12th century history?

In my own case, I had to travel to Biu Emirate in 2016 despite the security risks involved. In fact, I never knew about the emirate until I read A History of Biu by Bukar Usman. I didn’t know anything about the Bura/Babur people. But I was amazed by what I saw when I got there –how welcoming the people were and how beautiful the landscape and weather were, different from what I had experienced before then. I witnessed arresting valleys, tablelands, rocks, mountains and exotic culture. This is also a part of Nigeria with a warrior culture –you see it once you visit the Emir’s palace –and historical monuments that have been preserved for over 500 years.

You may not understand the self-sacrifice I put into this work. I braved the odds –the fear of Boko Haram and kidnapping – to travel there twice. While completing Yamtarawala, the Warrior King, I returned last year and spent days visiting places, including the Emir’s palace, meeting custodians of culture and visiting different local governments in the emirate to see things for myself. Above all, A History of Biu by Bukar Usman provided a rich repository of history and culture for me to explore as a writer. I am glad, today, the people are excited with how I have placed them on the literary and cultural map of the country. Let’s not forget, Borno State and the North East have known little peace for more than 12 years, but here I am, from a different part of Nigeria, celebrating their history and cultural heritage without commission. I am glad I am putting smiles on their faces in the face of overwhelming adversities. With funding, I will take this play round ID camps in the Northeast and theatres across the country for a change of literary narrative.

Are you thinking of writing more historical dramas after this?

Given the positive reactions I have received, I won’t rest on my oars. A Nigerian historian and playwright was so delighted at the NPL-CORA event about this play that he called me a prof. He told me that many historical personages and developments in the country were yet to be captured in Nigerian literature, compared to what the Western world had done with theirs. In movies, for instance, Western writers have dramatised personages like King Arthur and King Henry IV of England, Christopher Wallace of Scotland, etc, who shaped European history.

This is an aspect of literature we should explore further as writers; otherwise, this past would be lost forever. When you watch a play like Yamtarawala, the Warrior King, on stage you will appreciate the effort that went into the dramatic contraption.

One of the longlisted writers got

The longlist for the 2023 James Currey Prize for African Literature has just been released, what does this prize mean from African literature?

James Currey is a household name in African literature, thanks to what he did with the Heinemann African Series, which Abibiman is trying to resurrect. The James Currey Society is responsible for organising the James Currey Prize for African Literature, and has done well in this regard by creating a pan-African prize that has continued to excite African writers from all parts of the continent and beyond. As a jury chair for this year’s prize, it was exciting working with a dedicated panel drawn from Africa, Europe and South America. Reading through the manuscripts, you could see the enthusiasm by African writers to showcase what they have got. A prize like this is good for the continent. The icing on the cake for the winner of this competition is a cash reward in pound sterling and a trip to Oxford to attend the African Literature Festival. The visibility this prize offers for the winner and the African literati is enormous.

I understand you are planning to publish a book of interviews, Conversations with 50 African Writers, tell us about that.

A group of iconic writers and scholars such as, Professors Ernest Emenyonu, Tanure Ojaide, Niyi Osundare, Udenta Udenta, Charles Larson, Chimalum Nwankwo, as well as legends like Odia Ofeimun and B.M. Dzukogi, to mention a few, have told me repeatedly to put my greatest interviews together in a book form. They have pointed out that some of these interviews, including those with African literary giants and Africanists, like Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Kofi Awoonor, Gabriel Okara, Abiola Irele, Chimamanda Adichie, Eustace Palmer, to mention a few, should be republished for a wider, scholarly audience. And I think they are making sense. I am thinking of expanding the number to 100 African writers and scholars, because the work done in the last 18 years has been enormous. Journalists like us should be exploring these possibilities. This is the kind of book that easily becomes a bestseller globally, considering the big names one has encountered within a short time. It’s mind boggling.