What was his crime? He was perceived to be homosexual. When he reported this incident to the police, he was advised to leave the area if he wanted to avoid future ‘embarrassment’.

In June of that same year, another man, Tare, was abducted by four men in Woji, also in Port Harcourt.

The men claimed to be members of the neighbourhood security and they suspected Tare was a gay man. They beat him before releasing him in exchange for the names of other gay men in the neighbourhood.

Tare provided them with fake names even though the men had threatened to murder him if he lied. To avoid this threat, Tare had to relocate from the area.

A similar incident occurred in June 2015, this time in Apapa, Lagos. A young man named Caleb was stopped by a group of men on his way back from work. The men wanted to know if Caleb was a man or a woman because, they claimed, he was walking and behaving ‘like a girl’ – whatever this may mean.

The men beat Caleb, robbed him, and warned him against ‘walking or acting like a girl’ or risk being attacked again by them. Caleb’s friends and family advised him to move from the area.

These incidents – milder examples of violence against poor or lower middle-class Nigerians who are perceived to be gay, lesbian, or transgender – are documented in annual reports by human rights organisations in Nigeria.

In more tragic instances, young men and women have been killed by mobs, random strangers, or even family and acquaintances for their real or perceived sexual orientation (Are you gay? Are you a lesbian?) or gender identity (Why do you walk like a man? Why are you dressed like a girl?).

And so, for many, forced relocation is often the only way to avoid the threat of harm. But forced relocation is not a joke.

Already, in Nigeria, there is a growing community of internally displaced young people who, with little or no resources, had to flee communities where people threatened to kill or assault them for their sexuality. And yet, the Nigerian Constitution is clear that: “Every citizen of Nigeria is entitled to move freely throughout Nigeria and to reside in any part thereof, and no citizen of Nigeria shall be expelled from Nigeria or refused entry thereby or exit therefrom.”

But what happens when the people tasked with the protection of these rights are the ones who create unsafe societies? For instance, in January 2019, a Zonal Public Relations Officer for the Nigerian Police, Dolapo Badmos, posted ‘advice’ on her Instagram account warning that ‘if you are homosexually inclined, Nigeria is not a place for you’ and that those who were ‘homosexual in nature’ should ‘leave the country or face prosecution’.

“Leave the country”. This is sad at best and horrifying at worst. It is the kind of language that inspires, legitimises, or perpetuates the kind of violent acts that displaces fellow citizens and turns them into refugees.

As the supportive comments on her post show, this is the kind of language that emboldens mob action. It supplies the rationalisation for the idea that, somehow, sexual minorities are more intolerable to the community than violence against them.

We have a culture of violence in Nigeria. This is a culture that is detrimental to our general health as a society, and one that should worry any thinking person. There are enough problems that kill Nigerians daily without us needing to create even more.

Unfortunately, when it comes to issues of sexuality and gender, rationalisation overcomes rationality, and even the most educated people turn to prejudice. But logic does not care about prejudice: a society that continues to justify violence will simply never be safe for everyone. Hate strikes out blindly and indiscriminately.

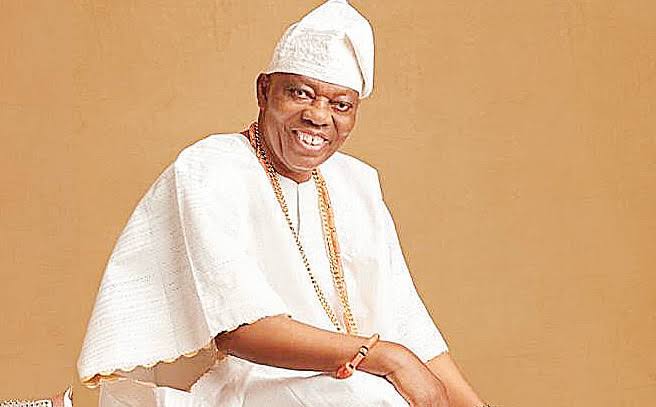

A note for Pius Adesanmni

Since getting news of Pius Adesanmi’s death, the daily dramas of Nigerian politics have seemed trivial things to me. But Prof Adesanmi was an academic who knew how to use that drama to produce knowledge. He was a believer in popularising researched knowledge, disseminating complex thoughts in engaging and accessible ways.

For me, he was an enabler and support system, a mentor who never hesitated to reference my thoughts despite his greater experience and expertise.

The loss from his death cannot be exaggerated. The world has lost a rare type of human, Nigeria has lost a rare type of intellectual, and I have lost a rare type of friendship. I thank his family for sharing him with us during his lifetime and I hope that his legacies will continue to be a comfort to them in years to come.

[ad unit=2]