Unfavourable working conditions and a general lack of attention to the health sector are leading causes of high migration rates among health workers in Nigeria. These continue to aggravate the country’s infant and maternal mortality, our investigation reveals.

Twitter was recently agog when a doctor, using the handle @wakawaka_doctor, shared his experience working in Nigeria as against working in Saudi Arabia. Supported by others with similar stories, the Twitter user insisted that the work input of doctors in Nigeria is poorly rewarded when compared to their counterparts in other parts of the world.

Worrying stats threaten Nigerian health sector

Although the claim by @wakawaka_doctor could not be verified, records show that more health workers have left Nigeria in the past one year. This is further complicated by the fact that there are not enough doctors in the “giant of Africa.”

In particular, doctors attribute the incessant migration to a poor working environment, salaries and incentives. According to one Aljazeera report, “While the annual healthcare threshold per person in the US is $10,000, in Nigeria it is just $6.”

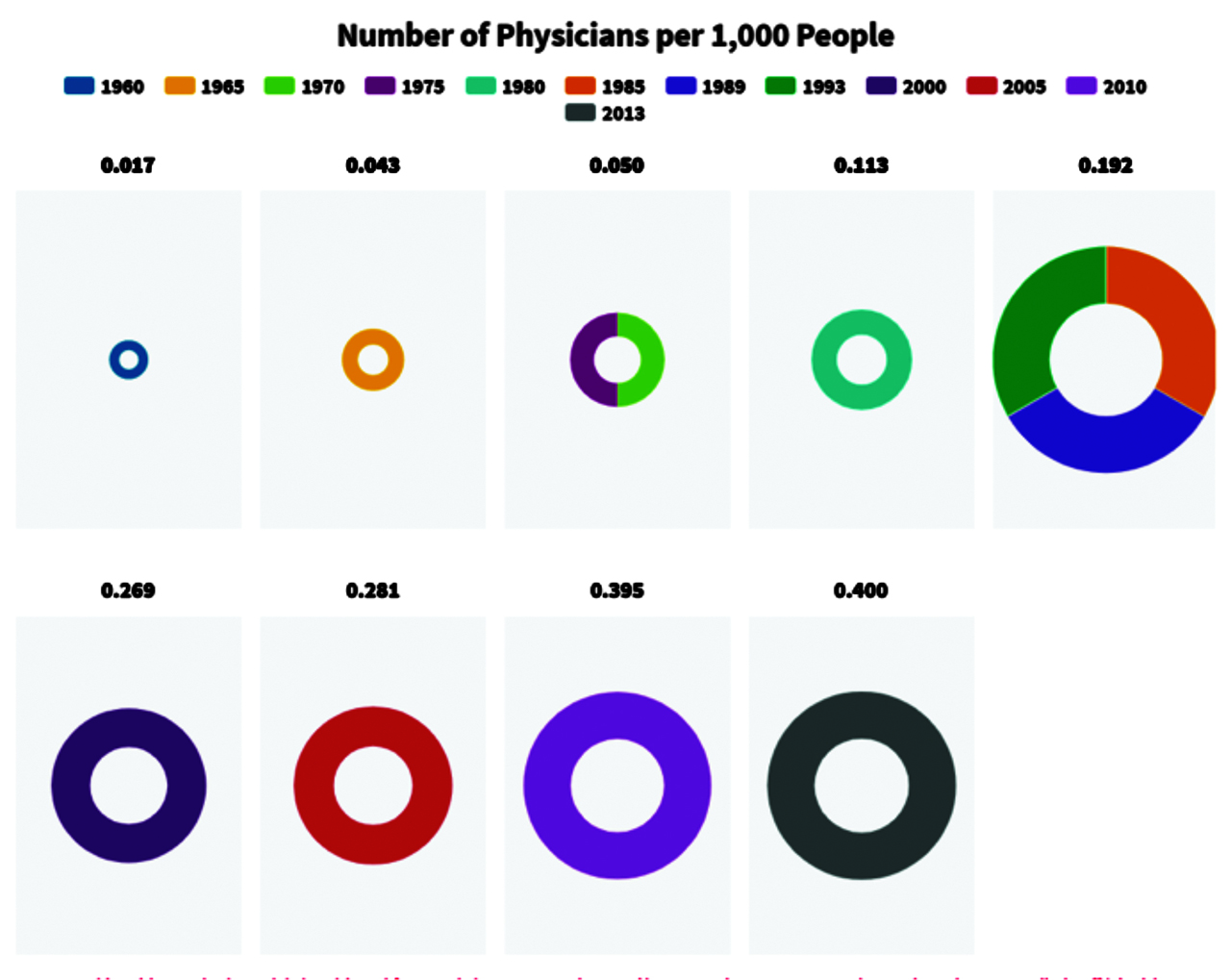

World Bank data shows that, since 2013, the ratio of doctor-to-patients has been pegged at 1 doctor to 40,000 Nigerians, which is a long stretch from the WHO standard of 1 doctor to 600 patients. There are 72,000 registered doctors with the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria with more than 30,000 practicing outside the country, according to the Nigerian polling organization, NOI Polls.

Another research by the NOI Polls revealed that “about 8 out of every 10 (88%) medical doctors in Nigeria are currently seeking work opportunities abroad.” This finding cuts across different levels and specializations.

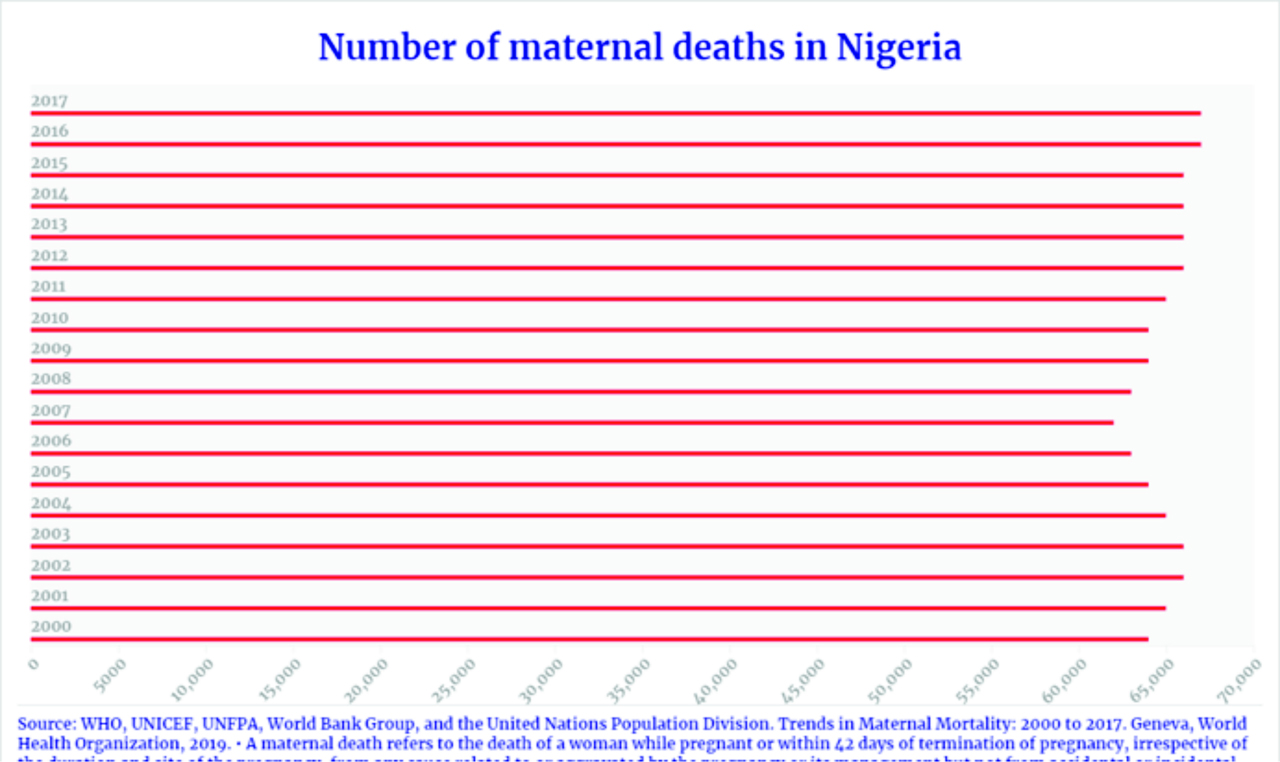

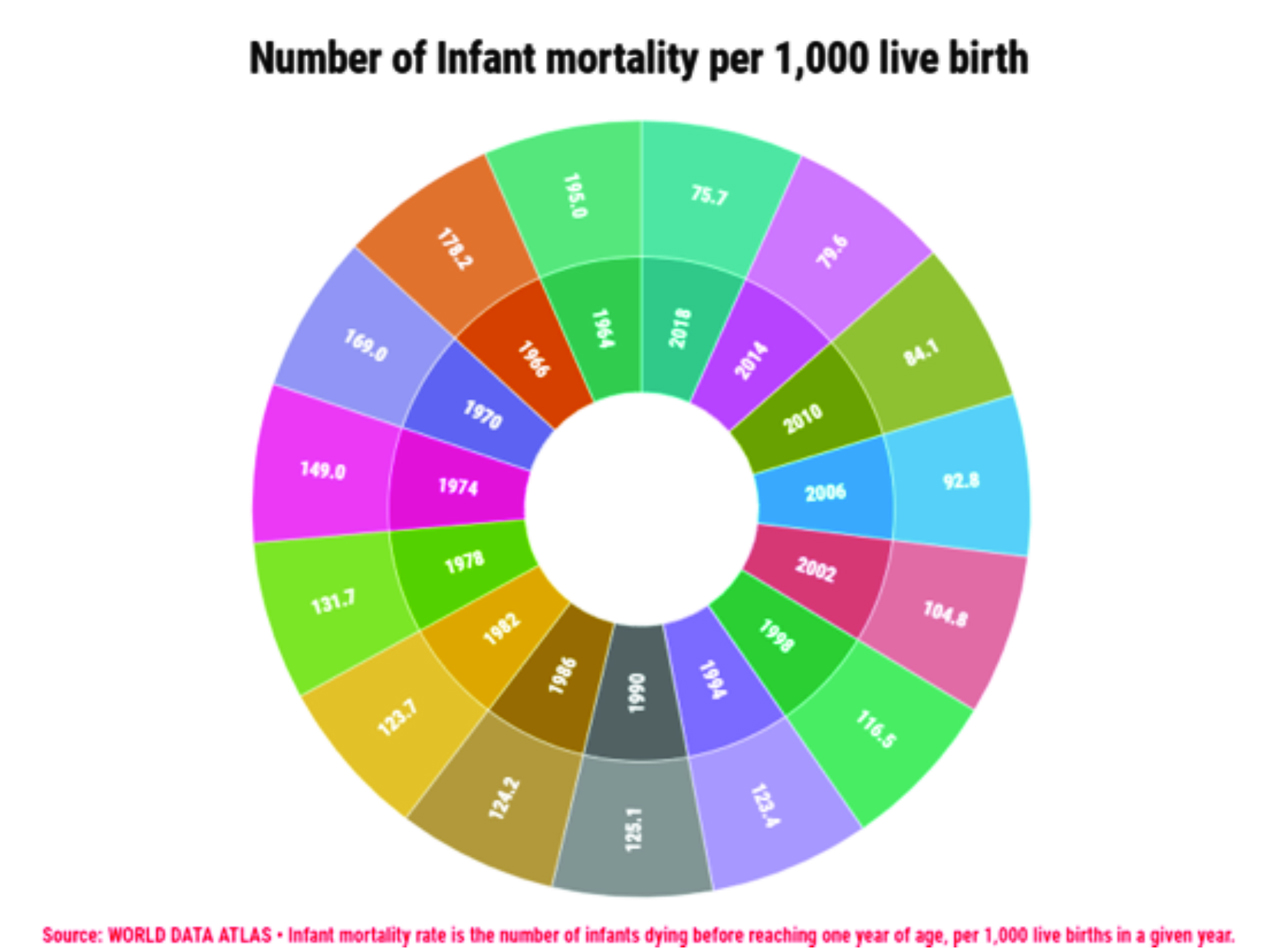

This, fortunately, or otherwise, has become Nigeria’s reality in recent times. It appears to have exacerbated infant mortality and maternal deaths, especially in conflict-affected regions of the country.

Acute shortage leads to longer waiting time

The high ratio of patients to doctors contributes to an increase in waiting time for expecting mothers and infants. We gathered this from an interview with a medical doctor who sought anonymity.

The doctor who works in the “Mother and Child” unit at one of the general hospitals in Lagos State disclosed that during the long waiting period, some of the pregnant women get exhausted. The waiting hour usually takes 4-6 hours in her hospital.

She also lamented that some childbirth emergencies are not attended to on time, as doctors are usually busy in the theatre performing emergency cesarean section. In the case of antepartum hemorrhage (bleeding during pregnancy) and depending on the severity, the woman may bleed to death. There might also be reduced blood supply to the baby and consequent foetal death.

The doctor also accounted that on average, they (each doctor) attend to 30-40 patients in a day. This overwork, juxtaposed against poor enumeration, could sometimes affect the quality of service the doctor gives to the mother or infant. And in their fatigued state of mind, they are also likely to make mistakes.

According to the doctor, the overwhelmed doctors fall ill often – sometimes with chronic ailments – because they hardly have time to take care of themselves. She shared that there have been cases of doctors dying from heart-related disease and cancer in recent times because they could not leave work to go for their medical check-up when necessary.

Widespread lack of commitment to public health

Visits to several areas of Surulere in Lagos State reveal how many of the Primary Health Care (PHC) centers suffer dilapidation and shortage of physicians.

The majority of the health facilities operate below capacity and cases that require urgent attention are transferred to the Ejire PHC, which appears to be a shining light in the Itire-Ikate Local Council Development Area (LCDA). The implication of this is that there could be serious complications that may lead to death if not properly handled.

Strangely, however, nurses and doctors in the maternity and infant section at Ejire refused to speak to our reporter who wanted to find out how they work. Still, it should be noted that they made efforts to attend to patients.

There was no doctor on duty at the Anjorin PHC when this reporter visited. The available nurse said they do not operate for 24 hours and that major health matters are often transferred to Ejire.

At the PHC in Airways (Ijesha), the PHC that runs over there operates for 18 hours with nurses sometimes used in place of qualified doctors. The assistant head of the medical service disclosed that the proper place to get relevant details from the headquarters at Yaba.

During another visit to the Ejire PHC, patients were seen being attended to by nurses. There was no doctor on the seat. The assistant head officer, Savage Simisola said that out of all the PHCs around Itire-Ikate Local Council Development Area (LCDA), only Ejire runs for 24 hours and this is due to the shortage of physicians available.

These are just a few of the numerous cases of the dearth of health workers and the unsavoury tales it brings to Nigerians.

Conflicts as impediment to stable healthcare delivery

The situation of healthcare is deteriorating in Northeast Nigeria. The high level of insecurity: kidnapping, bombing etc. in the region has further demotivated physicians to work in those regions.

Physicians who are committed to stay back to work are faced with the scourge of few facilities to work in as a result of the destruction of infrastructure in those regions. In a report by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), only half of the 700 health-care facilities are functioning.

In January, an ICRC- supported facility in Rann was burnt down. Health centers in Sabon Gari and Damboa have also been attacked.

A health worker in Maiduguri who requested anonymity shared with us that a number of midwives and medical doctors have been abducted in the last year.

This has taken a toll on child-birth, with infant mortality death at 150 per 1000 live births in the region. This is higher than the national average of 36 per 1000 live births.

This story was supported by Code for Africa via it’s Academy Hacks/Hackers Community Initiative.