Writer’s Note: As part of a Taz Panter Stiftung program bringing African journalists together with European experts to discuss African-European relations, we discussed the impact of the Ukraine war on food security in Africa. Being the only Nigerian journalist in the room, I was aware that the food crisis in my country was already at frightening degrees long before the war.

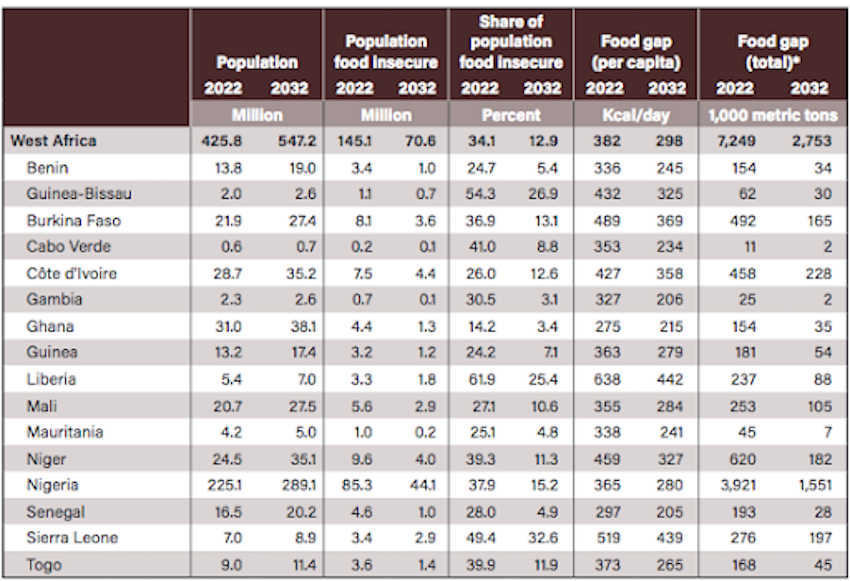

Nigeria’s food insecurity, long aggravated by insecurity in the major agricultural regions by Boko haram terrorists, Herdsmen and farmers conflict, climate change and economic shocks, as well as heavy reliance on food and seedling imports, continues to make it more difficult for people, particularly the poorest and most vulnerable, to afford food. According to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Nigeria had approximately 50% of West Africa’s food-insecure population in 2019, now worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic and insecurity. As of 2022, Nigeria has 85 million food insecure people, but USDA projects a 23% drop to 44 million people in 2032.

The Russia-Ukraine war began on 24 February 2022, causing a substantial spike in food prices in Africa and worsening the food insecurity caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Russia and Ukraine are the main exporters of staple produce like wheat, maize and vegetable oil that feeds most of the continent.

Source: USDA, Economic Research Service based on results from the International Food Security Assessment model.

Nigeria has approximately 62 million under-educated people living under two dollars a day for whom the term, food inflation means nothing. Whatever the reason for the food shortage, the average Nigerian wants to know what it has to do with the price of garri in the market.

Garri, a staple West African food, has steadily risen in cost since 2019. It is a grainy flour made mostly from cassava. Everyone eats it, every region makes it, and everyone can afford it, both rich and poor. It is eaten with different exotic soups as fine dining or simply with cold water and sugar as an instant snack. The price of garri is also how Nigeria’s masses measure food inflation. The degree to which the poor cannot afford to consume garri in its simplest form, not for nutrients but to stave off hunger, tells the human cost of food insecurity.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) describes food security as “when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”. Access, availability, choice, and sufficiency all of which are inadequate for many Nigerians.

The poorest households spend more than half of their income on food. Many who spend 50% of their salary on food face extremely difficult choices if food prices rise by 30%: To buy food or electricity? To send your children to school or buy new shoes because the old ones are coming apart? That is what rising food insecurity means.

The problem with food supply

Nigeria needs to produce more food to feed its growing population. However, the agricultural sector is facing several challenges, including low yields of major food crops such as rice and maize, lack of mechanization, which makes it difficult for farmers to produce food on a large scale, high cost of agricultural inputs, such as fertilizers and pesticides, lack of irrigation, which makes it difficult to grow crops during the dry season, climate change, which is causing erosion and desertification in the food belts, and lack of storage facilities, which leads to food waste. The high cost of transporting food, lack of mechanization, and insecurity in the northwest and northeast regions also affect food production, creating a supply problem. Each year, about 17 million Nigerians face starvation due to food waste.

Kelvin Ayebaefie Emmanuel, a public policy advisor and CEO of Diary Hills Farms, believes that the financial model for agriculture in Nigeria is wrong. He says a lack of transparency in failed direct intervention initiatives like the Anchor Borrowers Programme – introduced by ex-President Muhammadu Buhari in 2015. “The government gave money to people who were either not farmers or were not willing to pay the money back, and you could not see the result in the output.”

The effect of International food prices on urban food security

Nigeria faces increasing food insecurity in urban areas despite producing significant amounts of food due to high consumption of imported foods, which are expensive and dependent on foreign exchange. For example, Nigeria does not grow enough wheat or rice to meet its domestic demand and imports them in large quantities. When international food prices rise, the reliance on imported food crops that are difficult to grow in Nigeria costs the country scarce foreign exchange, making it more vulnerable to food price shocks.

Luther Lawoyin, the CEO of PricePally, an online food market, says there is a knowledge gap between Nigeria’s urban consumers and local producers on the cycle of food production and availability and how it affects food prices. He explains that food prices typically increase during the off-season when items are not as plentiful, except for seasonal changes like Christmas and Salah celebrations when the food prices surge. “There is a month-on-month cycle of food price increase. And it’s about when food items are off-season or in-season. During the off-season prices really go up. Vegetables are the SI units for knowing when food prices are more, for example, from August to February/March, you should expect vegetable prices to keep declining.”

As overall inflation rises, Nigerians tend to buy food in smaller quantities, sacrificing nutrients and dietary value for more bulk and density. Supplementary vegetables like cabbages and fruits are then considered luxury.

Lawoyin cites improper storage and transportation as a major factor contributing to food price increases. He points out that Nigeria does not have a cold chain system for transporting perishable foods, like tomatoes. It means that tomatoes often spoil before they reach consumers, which drives up prices. Food markets in the villages abandon perishable foods and fruits to rot if there are no customers to buy at the prices or volume that prevent wastage the next day. It takes approximately 21 hours for a truck carrying tomatoes to drive from Maiduguri to Lagos (northeast to southwest), about 1498 km. “If you want a low-hanging fruit to solve this problem, move food items by rail, you can cut the cost of food by 20-25% just doing that.”

Smallholder farmers

Smallholder farmers, mostly farming families in villages, are the backbone of Nigeria’s food supply. These farmers use crude tools and traditional farming methods, which are not sustainable for a growing population while being wiped out by farmer-herder conflict and terrorism.

Farmers cannot afford to build irrigation clusters that allow for year-round food production. These are irrigated tracts of land suited for growing crops during the dry season. Tractors are needed to open up fresh land, but they are scarce in Nigeria, and renting one for a day costs between 100,000 – 180,000 ($134-241).

Re-organizing smallholder farmers into credit-guaranteed cooperatives would help farmers access the resources they need to improve their productivity. “In Ethiopia, the government developed extension services, banded smallholder Farmers into cooperatives carried out land opening and land preparation, and mechanized agriculture to accelerate [wheat] production. These are things in which the Nigerian government has not been successful,” says Kevin Emmanuel.

So how does the war in Ukraine affect food security in Nigeria, you ask?

The war in Ukraine and Russia has affected Nigeria’s wheat and fertilizer supply. Producing only 2% of the wheat it consumes, the country imported $3.23B of wheat in 2021, becoming the second-largest importer of wheat and wheat the second-largest import in Nigeria. The total sum of imports from Russia and Ukraine is $983M. Wheat is used to make many food products such as semolina, noodles, bread, and spaghetti and prices of these commodities have risen drastically. Bread, which sold for ₦550 now sells at ₦1100, and the cost of a bag of fertilizer has increased from ₦11,500 ($16) to ₦32,500 ($44) in the last 18 months.

Dr Tedd George, founder and Chief Narrative officer of Cleo’s Advisory which focuses on the African commodities markets and commodity supply chains, says the war in Ukraine is not directly responsible for the food security issues in Nigeria but an aggravator.

“So the thing in Nigeria, which is incredible, is Nigeria is a soft commodities giant. Now, people don’t see it that way.” He explains. “They see it as a hydrocarbon giant, that’s where all the foreign exchange revenue comes from. But it is the largest producer of soft commodities in Africa after South Africa. The largest producer of cassava and yams in the world, rice, sorghum, all of these kinds of foods. So there’s a huge amount of food production going on and yet Nigeria is probably the largest importer of food in Africa.”

Food imports are controlled by global market pricing; however, because the food supply chain was disrupted by the war, and substantial quantities of wheat sent to other countries from Ukraine and Russia ended, countries were forced to either stockpile their supplies or get them elsewhere. The price rises, affecting the direct flow of wheat and causing Nigeria to pay more for wheat imports.

Kevin Emmanuel suggests the backward integration of wheat in Nigeria would involve growing wheat instead of importing it. He cites Brazil as a tropical country that successfully grows wheat. George recommends that it is too costly for Nigeria to develop new wheat seedlings or different ways to grow wheat in an unsuitable climate. He suggests that Nigeria focuses on improving the taste and quality of cassava flour. The country has planned, unsuccessfully for years, to integrate a blend of flour that is a 50/50 blend of cassava flour and wheat flour to upset the rising cost of wheat importation.

Is there a solution to food insecurity in Nigeria?

Dr Tedd George says it could all depend on politics. The Nigerian government should implement two policies to improve food security: (1) a universal payment to households and (2) a boost in the consumption of local foods to reduce reliance on imported foods. A universal payment of $50- $100 (45,000-90,000 naira) to households would be more effective than subsidizing the price of food, another solution inspired by Brazil under the administration of President Lula da Silva (2003–10).

Dr George points out that food subsidies can lead to corruption, fraud, and market distortions. However, a universal payment, distributed fairly and efficiently, would give households more freedom to choose how to spend the money, which would likely lead to a more efficient use of resources.

On the surface, it seems simple what Nigeria should do to fix the rising food insecurity if there is political will: provide transport and storage infrastructure, support mechanized industrial farming through progressive government policies, create cooperative financial systems that support smallholder farmers, and tackle insecurity. Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu has declared a state of emergency on food insecurity in the country, making similar pledges about this issue to past governments. Recently, the country signed a food security and agricultural advancement deal with Cuba. It remains to be seen if Nigerians will get hungrier or take a few steps towards the FAO description of a food-secure people.

[ad unit=2]