The fertility industry in Nigeria is growing at an unprecedented rate, offering hope to thousands of couples struggling to conceive. But beyond the promise of scientific advancement lies a controversial and largely unregulated practice: egg donation. With more young women turning to this method as a quick financial solution, concerns about exploitation, health risks, and ethical boundaries are mounting, MOYOSORE SALAMI writes.

The fertility industry in Nigeria is growing at an unprecedented rate, offering hope to thousands of couples struggling to conceive. But beyond the promise of scientific advancement lies a controversial and largely unregulated practice: egg donation. With more young women turning to this method as a quick financial solution, concerns about exploitation, health risks, and ethical boundaries are mounting, MOYOSORE SALAMI writes.

On a bright, November morning, Tanya, a young Nigerian lady, arrived at a Lagos fertility centre after an agonising back and forth discussion with her agent.

Seven days earlier, she had started taking hormone injections to stimulate her ovaries into producing mature eggs, part of the process to get her body ready so that the doctors could extract them.

Tanya is one of the many young ladies drawn into the growing world of female egg donation, a practice that has quietly burgeoned into a thriving trade in Nigeria’s fertility industry.

“How are you feeling?” the doctor asked her, as a matter of routine not for special attention.

“I’m fine,” she said, lying about her status.

She was bitter. The palpable anger could be felt in her breath. Nature was not kind to her, she thought. What she never believed would happen to her was gradually unfolding. Was it greed or to help humanity, she didn’t know. But she was angry that it was only the children of the poor that were involved.

After some minutes, the doctor placed her in a surgical suite in the clinic. She was given intravenous sedation to minimise discomfort during the procedure.

A thin needle, guided by ultrasound, was driven through her vaginal wall to reach the follicles that contained eggs. The needle was connected to a suction device and test tube, and the fluid and eggs were pulled into it.

The process was repeated for other follicles in both ovaries. She was later taken to a recovery room and allowed to rest for a few hours.

That done; the eggs were examined and taken to a laboratory for evaluation and preparation. They were selected based on maturity for fertilisation.

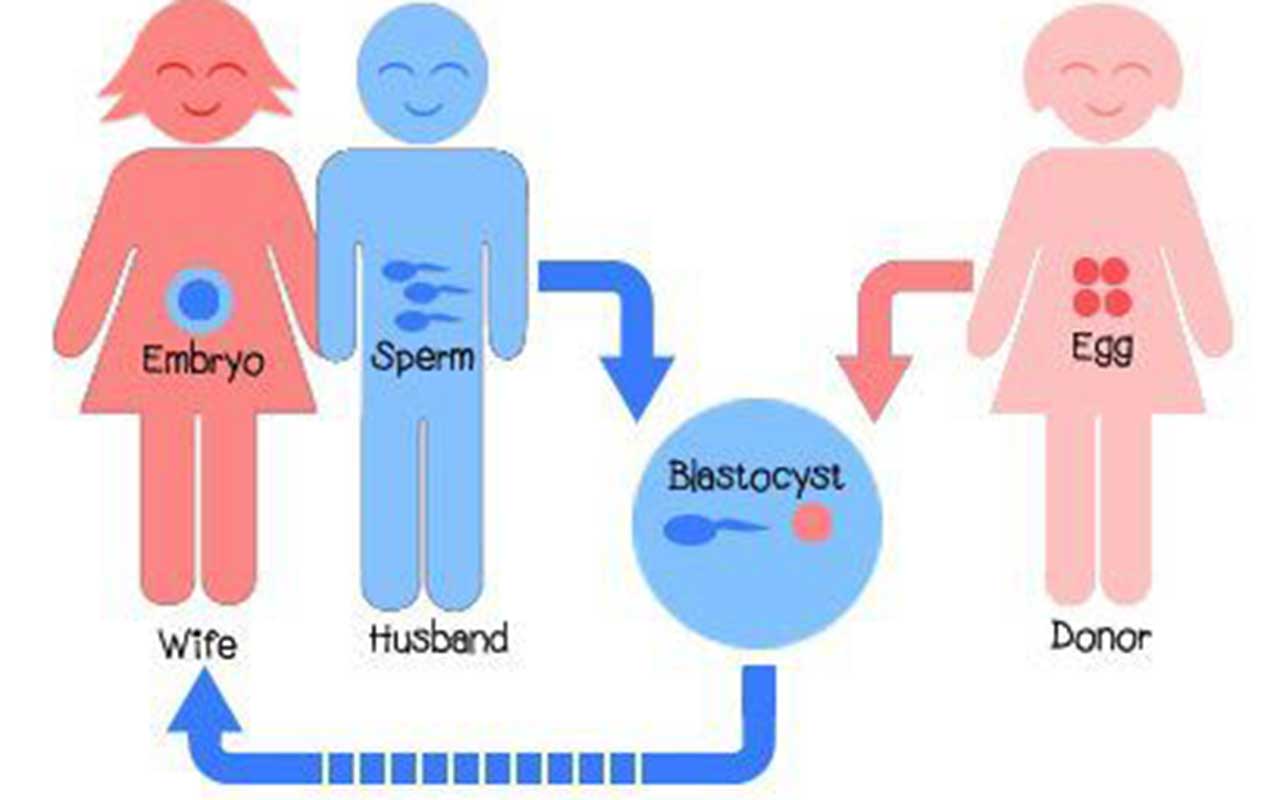

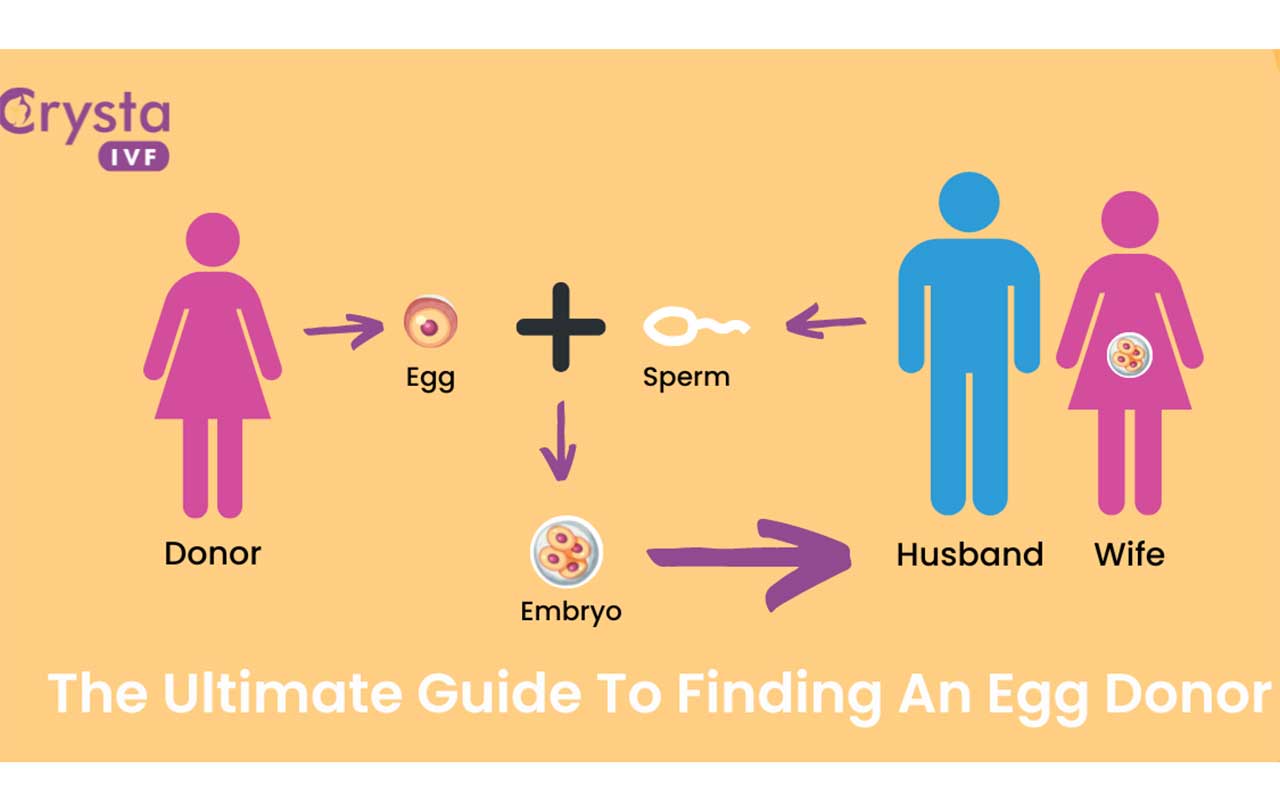

Egg donation involves an egg cell, also known as an oocyte, being extracted from a donor and utilised to create an embryo during the process of In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF).

Egg extraction procedure, also known as egg retrieval, is a minimal surgical procedure that removes eggs from the ovaries. The procedure is typically performed in a hospital or fertility clinic under sedation or general anaesthesia.

The process of egg donation is neither simple nor without risks involved. Women are subjected to a series of hormonal treatments designed to stimulate their ovaries to produce multiple eggs. The side effects can be severe, ranging from mood swings and weight gain to more serious complications such as Ovarian Hyper Stimulation Syndrome (OHSS).

Despite these risks, the practice continues to thrive, fueled by a mix of financial desperation among donors and the intense desire for children among recipients.

Tanya, however, does not agree that it is risky. “I don’t see anything bad in it. I’m not doing anything illegal or harmful. I’m helping couples who can’t have kids, and at the same time, I’m able to support my family. It’s definitely better than doing something like prostitution or getting involved in crime.

“This is my way of surviving, and I’ll keep doing it as long as I can. It’s a way out for many girls like me who are struggling to make ends meet.”

Sharing her experience with The Guardian, Bimpe Ojo said she felt physical pain, emotional stress and a sense of detachment from the process when she first donated her egg.

The screening process and procedures were very strict. They took her blood sample, had tests done for genotype, HIV, hepatitis, and they asked many questions about her health and medical history. Afterwards, she was told to come back during the beginning of her menstrual cycle.

“I was very nervous and I cried inside of me. They paid me N150,000 for the procedure,” Ojo said

“This is the second time that I’m donating my eggs. I got N250,000 the first time. The process isn’t as painful as people say; you just feel a bit uncomfortable afterward, but it doesn’t last long. I don’t mind doing it again because the money goes a long way. It helps me take care of myself and my family, and in this economy, that’s what matters,” Amarachi, a young lady, who runs a beer salon, revealed.

“But that is not all. It is not just about the money for me. I also get paid N20,000 whenever I bring another girl to donate her eggs. It is like a referral bonus. I have already introduced a few of my friends to this clinic, and every time one of them completes the donation process, I get a cut. To be honest, it’s become a side hustle for me.”

For Cynthia Ikechukwu, a chance meeting with another lady brought her closer to this fate. The 38-year old lady said, “I was refused opportunity to donate. I was asked how old I was and when I said 38, I was told to go home. I was not given anything. This made me cry.”

Take the case of Shade Adeoye, a 24-year-old university graduate, who had been struggling to find stable employment since completing her education, the money came at the right time.

“I was desperate, my family was depending on me, and I had no other way to make ends meet,” Adeoye noted.

Ngozi, a 24 year-old who had donated eggs three times, told The Guardian that: “The money was good, but no one warned me about the complications I might face later. Now, I’m worried about my own ability to have children in the future.”

Recently, a viral message on WhatsApp warned mothers to pay close attentions to their girl children. The message reads thus: “So, a very close friend of mine has a daughter of 21, who is schooling in one of the universities in the east. She came around for holiday and then fell sick last Thursday and was taken to the hospital for proper medical care. During the process of check up, her mum noticed a scar under her pelvic and she got worried, because according to her, her daughter has never had any surgery not even minor or major. So, she was wondering where the scar came from and the cause.”

She continued, “long story cut short. After much interrogation and the girl’s refusal to speak up, she called me to come over. On getting there, I met her in real tears and I asked what the problem was and she asked her daughter to open her tummy and show me what she saw. I saw it and then asked questions and she said her daughter has refused to tell her how she got that scar.

She continued, “long story cut short. After much interrogation and the girl’s refusal to speak up, she called me to come over. On getting there, I met her in real tears and I asked what the problem was and she asked her daughter to open her tummy and show me what she saw. I saw it and then asked questions and she said her daughter has refused to tell her how she got that scar.

“I immediately took the girl outside and interrogated her and she opened up to me that a friend of hers introduced her to a business in school last year, that she did it and was paid N200,000. And she said they have doctors they meet when they are ovulating to buy their eggs. So, what they do is, they have to open them up, take the eggs and then cover them up again.”

A second year university student in Lagos, Oyinda Ige, said the pressures of tuition, rent and daily living expenses weighed heavily on her.

So, when her friend mentioned as a quick way to earn money, donation of eggs, it sounded almost too good to be true.

Within weeks, she had undergone the necessary medical tests, given hormone injections, and thereafter, doctors harvested her eggs.

The promise of a substantial payout overshadowed her initial fears, but the experience left her with more than just a fatter wallet, a complex mix of emotions and long-term health concerns.

While some ladies use the money from egg donation to further their education or start small businesses, others find that the money does provide only a temporary relief from their financial struggles.

Efe, an 18-year-old donor, used her earnings to pay for a professional course she hoped would land her a better job.

“It helped me pay for the course, but finding a job was still difficult. Now, I’m considering donating again because I’m back to square one, financially.”

Bisi Adekanmbi, who donated eggs at 17, is still disturbed emotionally with the thought of children being born from her eggs without ever knowing them.

“It is strange to think that I might have a child out there who I will never meet, this psychological burden can be heavy, and particularly in a culture that places high value on biological ties and family lineage,” she lamented.

Growing Rate Of Infertility

ACCORDING to the World Health Organisation (WHO), infertility affects one in four couples in developing countries, and Nigeria is no exception.

Experts say 60 per cent of gynecological consultations in Nigeria are related to infertility, while 25 per cent of couple struggle with the condition.

As more Nigerian couples struggle to conceive, fertility clinics have become centres for In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) and egg harvesting services. However, the industry is largely unregulated. This has encouraged proliferation of quacks who often do more harm than good.

The booming trade in egg is not just a reflection of the demand for fertility solutions; it is also a symptom of deeper societal and economic issues, as many of these ladies who become egg donors are young and financially vulnerable, often university students or recent graduates struggling to make ends meet.

The decision to donate eggs can seem like a lifeline in the country.

For most of them, the promise of a quick payout, sometimes, as much as N200,000 per donation, can be too tempting to resist. But this financial incentive comes with a price.

Fertility starts to reduce after the age of 30, and this reduction happens faster after the age of 35.

By the age of 43 or 44, most women’s eggs will be of poor quality and, while possible, it is very rare to get pregnant.

A woman’s ovaries stop producing eggs and she goes through menopause when her body has no more viable eggs left. This usually happens between the ages of 45 and 51.

Despite the progress in Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) practices, concerns remain about the exploitation of egg donors, particularly, young women lured by the promise of financial gain without fully understanding the risks involved.

In 2019, the Lagos State government unveiled a guideline that will ensure that fertility specialists in the state conform to international best practices in their operation.

At the book launch, titled, ART Practice in Lagos State: Regulations and Guidelines, the former Commissioner for Health, Dr Jide Idris, said the necessity of these regulations owe much to the increasing demand for ART services and the rise of advanced medical procedures.

Idris explained that efforts to develop these guidelines started in 2013, driven by the need for policy regulations and ethnical frameworks based on the global best practices, which led the way in establishing a regulatory framework for ART, even though no national guidelines exist.

“By 2017, the number of registered ART clinics in Lagos had grown significantly, from just a few in 1999 to over 20 by December 2018. However, many clinics were still unregistered and operated without clear legal and ethical guidelines,” he said at the guideline unveiling.

Sadly, the current system exploits vulnerable women, turning their reproductive potential into a commodity owing to lack of strong national guidelines exacerbates the situation, as the fertility industry continues to grow in a largely unregulated environment, placing the health and well being of donors at risk.

The occurrence, which is either underreported or overlooked in Nigeria, is becoming increasingly popular due to the financial gain.

While ART offers hope to many families, the absence of proper oversight risks turning the fertility industry into a source of harm.

However, the financial relief from egg donation often comes at a cost. Donors are not fully informed about the medical risks involved.

Findings revealed that OHSS, a potential side effect of the hormonal treatments used to stimulate egg production, can cause severe pain, blood clots, and fertility issues.

For some women, the experience can lead to emotional and psychological stress, particularly in cases where they are unaware of the potential complications.

Beyond the physical and economic implications, egg donation also carries significant ethical and cultural dilemmas.

In a society where fertility is closely tied to a woman’s identity and worth, the secrecy surrounding egg donation can have profound effects on a donor’s personal life.

Many donors are reluctant to disclose their involvement in the trade, fearing stigmatisation or judgment from their communities and potential partners.

Many donors are reluctant to disclose their involvement in the trade, fearing stigmatisation or judgment from their communities and potential partners.

The lack of robust regulation in the egg donation industry further complicates the situation. With few legal protections in place, donors are often left vulnerable to exploitation.

Clinics may not provide adequate information about the risks, and there is little oversight to ensure that the procedures are conducted ethically.

How many even know that women should only donate their eggs six times in a lifetime as recommended by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine?

In response to growing concerns about the exploitation of young women, an embryologist, Macaulay Benson, clarified that egg donation is a voluntary process, strictly regulated by law.

He said the practice is not driven by financial incentives, but by a donor’s willingness to help couples facing fertility challenges, particularly, those of advanced maternal age.

“Egg donation is freewill, nobody is forced into it. Donors choose to help couples in need and there is no payment involved. Egg donation is not something that can be bought with money,” Benson said.

He further explained that the process is transparent and bound by legal and ethical standards and dispelled the misconception that young women are being lured into donating their eggs for financial gain, stressing that donors are not compensated for their contribution.

“There are no secret transactions or hidden agendas. The process follows strict guidelines and donors must meet certain legal criteria. For instance, no hospital in Nigeria would accept a 16-year-old as an egg donor. The legal age limit for donors is 18 and above, depending on the case.

“Egg donation is guided by regulations and there are legal documents involved. The narrative that young girls are selling their eggs for money is simply not true.”

However, a legal expert and advocate for women’s health, Aisha Bello, stressed the need for stricter regulations.

“We need comprehensive guidelines that protect the rights and health of donors. Without proper regulation, we risk turning these women into commodities in a largely unregulated market. We need to ensure that these women are fully informed and protected. It is also a call for a cultural shift, where the decision to donate eggs is respected but also approached with full awareness of its implications,” Bello said.

According to her, young Nigerian women should be educated to make informed choices about their bodies and future, free from the pressures of economic hardship or exploitation.

By addressing the root causes of why women feel compelled to donate eggs and providing them with alternative opportunities for economic advancement, Nigeria can begin to mitigate the risks and ensure that the egg donation industry serves the needs of all parties involved.

She added that there should be mandatory counseling for donors and recipients, as well as clearer legal frameworks to govern the industry.

According to a gynecologist, Dr. Eniola Oyekan, “Egg donation can be a life-changing opportunity for women struggling with infertility, donors should be fully informed of the potential risks. The hormone treatments used to stimulate egg production can have serious side effects, including OHSS, which can lead to complications if not properly managed.

“Once the eggs are harvested, the donors are often left to deal with the physical and emotional aftermath on their own. There is an urgent need for stricter regulations to protect these young women, who may not fully understand the impact of the procedure on their health.”

Oyekan also pointed out the lack of regulation in Nigeria’s fertility industry, which often leads to clinics cutting corners to maximise profits.

“Many of these clinics don’t follow the best medical practices. The donors, who are often desperate for money, are not fully informed about the potential consequences on their reproductive health.”

A public health advocate, Dr. Ibrahim Oyeleke, urged that the government needs to step in to protect both donors and recipients.

“There is a need for comprehensive legislation that ensures the safety and well-being of donors which must include mandatory counseling, informed consent, and a cap on the number of cycles a woman can undergo.

“The growing demand for egg donation, particularly, among young women, raises significant ethical questions. Are these women fully informed about the risks, or are they being lured by the financial incentives? There must be stricter regulations to protect donors from exploitation and to ensure they are making informed decisions.”

On his part, a fertility specialist and bioethicist, Dr. Segun Oni, said: “While egg donation can be a lifeline for those struggling with infertility, we must consider the broader implications, the egg, once donated, undergoes a process of fertilisation and implantation, leading to the birth of a child genetically unrelated to the donor’s life. This raises questions about genetic legacy and the potential psychological impact on both the donor and the child.”

He also noted the societal ramifications, warning that the increasing commercialisation of egg donation might lead to a commodification of human life.

He also noted the societal ramifications, warning that the increasing commercialisation of egg donation might lead to a commodification of human life.

“If not carefully regulated, we might face a situation where egg donation becomes less about helping others and more about financial gain, leading to ethical dilemmas and social consequences, It is important that we balance the needs of those seeking to conceive with the ethical considerations that preserve the integrity of human life and society.”

In 2014, the National Health Act was enacted. It is currently the only legal framework governing egg donation in Nigeria. Section 53 of the Act criminalises the exchange of human tissue and blood products for money, even allowing for a fine and/or up to a year’s imprisonment for those convicted.

But many of these ladies were unaware the law existed and unsure how it would apply to egg donation.

Only recently, the Global Prolife Alliance (GPA) urged the National Assembly to repeal the National Health Act of 2014, because it endorses ovarian eggs poaching.

In a petition to President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, Vice President Senator Kashim Shettima, Senate President Godswill Akpabio, Speaker of the House of Representatives, Hon. Tajudeen Abbas, Inspector-General of Police Kayode Egbetokun and human rights organisations, among others, the group said the content and character of the National Health Act 2014 surreptitiously endorsed human organ trafficking and ovarian eggs poaching.

The petition, signed by its chairman, Dr. Phillip Njemanze, reads: “Our quest for justice led us to the forefront of a battle against the sinister provisions concealed within the National Health Act of 2014 (NHAct2014), which clandestinely endorse the barbaric practices of human organ trafficking and the ruthless poaching of human ovarian eggs.”

The group alleged that IVF clinics stand poised to plunder the wombs of the nation, their claws sharpened on the edge of desperation.

“Organs and ovarian eggs will be poached from apparently healthy persons without their consent under the disguise of ‘emergency’. They have ensured that organs and ovarian eggs can be collected without consent in Section 48 (1) (b) that the consent clause may be waived for medical investigations and treatment in emergency cases.”