If you have a favourite artist that popped up on your mainstream radar four years ago or before, you will discover that they are no longer being represented by the company and team that brought them to you.

All of your favourite musicians are leaving the companies that birthed them and chasing new frontiers. The language is generally the same: “We will no longer be renewing the contract, we are proud of the work we have done together…” But the truth stares everyone in the face; these musicians are departing from these record labels, taking their business with them and pitching it elsewhere. Where one company loses, another is either formed or a bigger company announces them as part of a new push.

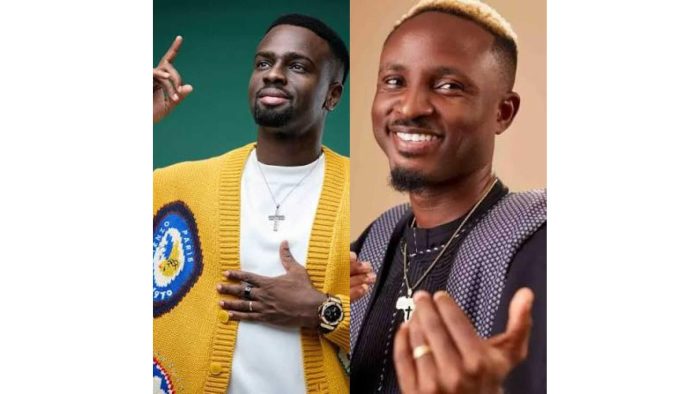

In the past year, a number of key musicians have announced their exit from record labels. Tiwa Savage has finally made public, her exit from Mavin Records after 7 years of stellar delivery. Tekno hasn’t announced, but his rocky deal with Made Men Music Group and Upfront and Personal, ended at the turn of 2019. Simi, the darling of X3M Music, who dropped her first single ‘Tiff’ in 2014, no longer walks through those doors with a binding contract. Reekado Banks announced his departure from Don Jazzy himself. He didn’t wait to synergise the announcement with the company. Ycee, the former golden boy of Tinny Entertainment, packed up and disappeared from the label.

[ad]

All of these appear to be great for the musician. They are the ones who have it good. From obscurity, backed by funding and talent, they have worked their way up from the bottom to the privileged level that they have now. If the duration of the deal that facilitated that growth and prosperity is legally over, there’s nothing holding them back. A lot of them usually don’t renew the deal, regardless of the terms offered. Freedom from having to split their earnings with a label structure is a basic motivation to not sign. Also, someone might be waiting in the wings with a bigger check, or better investment strategy, or even a more efficient way to market and distribute their music. Regardless, it is generally seen as growth in the industry, some sort of coming of age rite that is celebrated.

Significantly, artists regard their first major deals in Nigeria like a passage through a formative family.

Their birth is marked by 0the signing, and if their stars align and the investment is right, they grow through childhood into adolescence. Adulthood is attained if they blow. After that, everything else is just a preparation for exit. They have to leave home now. Except in rare cases, no one renegotiates their deal with their labels.

They don’t renegotiate or extend these deals for a number of reasons. Chief among them is a burning desire to receive a larger percentage of their income. When they first agreed to a deal, they were desperate musicians, hopeful for a shot at the big leagues. The deals reflect this lack of leverage on their side, and they are signed up to clauses and terms that require them to protect the investment of the record label by giving away a huge part of their income. No artist likes this. They believe that they deserve more, and push for it the first chance that they get.

Artists generally outgrow their record labels in Nigeria. If a local company grooms and blows an artist to international recognition, there’s the danger that the company will lose that artist to a larger firm who can offer more services or help them grow faster. Sometimes, both companies partner and split responsibilities in a joint venture deal. But much of the time, the artist will gravitate to the person that offers him a better deal. The local company has to scale and grow to meet the demands of their star artist, or they run the risk of losing a valuable asset.

Also, artists generally would love to start their personal empires. Many can’t get equity from the record labels, most don’t even want it. Being a boss has such a strong pull on many, and they would sacrifice a lot to sleep at night as “bosses” of their firms, and their destiny in their hands. It also makes their job easier when they discover that they can provide their funding, and also have access to all the platforms that they need to promote and market their art. Whatever their label did for them, the small nature of Africa’s music business terrain ensures that they can continue to have that access. Take away funding, and the labels mostly become redundant.

The result of this exodus is that we have moved from an industry of record labels to a system of teams: Artists who can generate a funding simply builds a team to handle their business, and partner with investors who are looking to make gains in the sector. That’s why you keep hearing Nigerian artists without a label structure. If they announce a new label, it will simply be a one-man company that caters to their personal and business needs. Very few artists remain after their deal. That’s why the label system in Nigeria is dead.

What labels need is to move from labels into becoming record companies. They need to invest in more arms of the business, opening new streams of income and offering more services beyond what they currently do. Thinking infrastructure is hard, and needs more resources and investment. Mavin Records recently acquired funding from Kupanda Holdings, an international investment and advisory firm. With that money, they are expanding their business and building properties beyond sinking their money into trying to break an artist. The old models are obsolete now. The market is demanding for more, and very few local music companies have the money or the “sense,” to be able to recognise and restrategize. Until then, the exodus continues.

[ad]