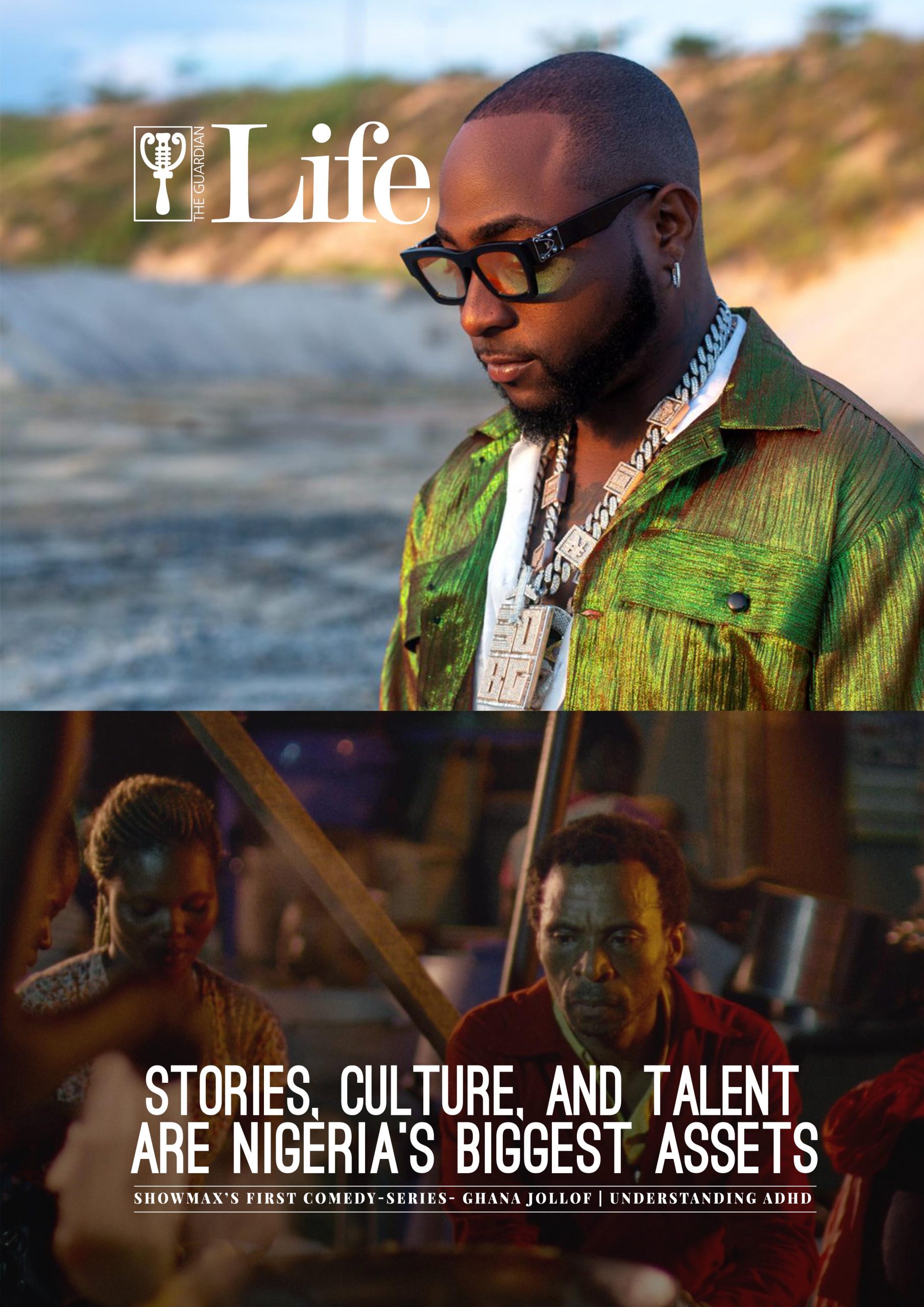

Exploring the commercial value of Nollywood, Afrobeats, and Nigeria’s technology ecosystem to the world.

We often think and speak of things Nigeria can export in tangible terms. We talk about oil; we talk about rice; we talk about wheat and other agricultural products. Sometimes, we talk about intangible things, but perhaps not often enough. We talk about how Nigeria can export some of its services to the world, especially in the financial industry. But there are far more options to explore.

Stories, culture, and talent are three of Nigeria’s most priced assets, and they have been for many years. From the moment Nigerians realised they could package culture into stories and develop themselves into world-class talent, the door opened up for immense opportunities.

[ad]

What’s this world without stories? What’s life without our ability to weave narrative threads through everything – great and small, significant and insignificant, extraordinary and mundane? The stories we tell ourselves and the stories we tell about ourselves are the vehicles that drive us, the ingredients that make existence flavourful, and the hands that mould how we think and feel about each other. Stories are what make us human.

In his critically acclaimed book, “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind”, Israeli historian and philosopher, Yuval Noah Harari, writes that our unique ability as human beings to tell stories has enabled us to imagine things collectively.

This ability to imagine things and tell stories allows us to cooperate flexibly in large numbers and in such a way that is unique to our species. It is also what makes us so powerful and drives the world as we know it, from business to politics, academia, religion, and entertainment. In many ways, stories form the basis of culture, and it is through culture that we influence one another.

It is through this lens that we must understand the impact and potential of Nigeria’s entertainment industry, from our films and even the comedy skits we watch online.

The stories we tell make us who we are

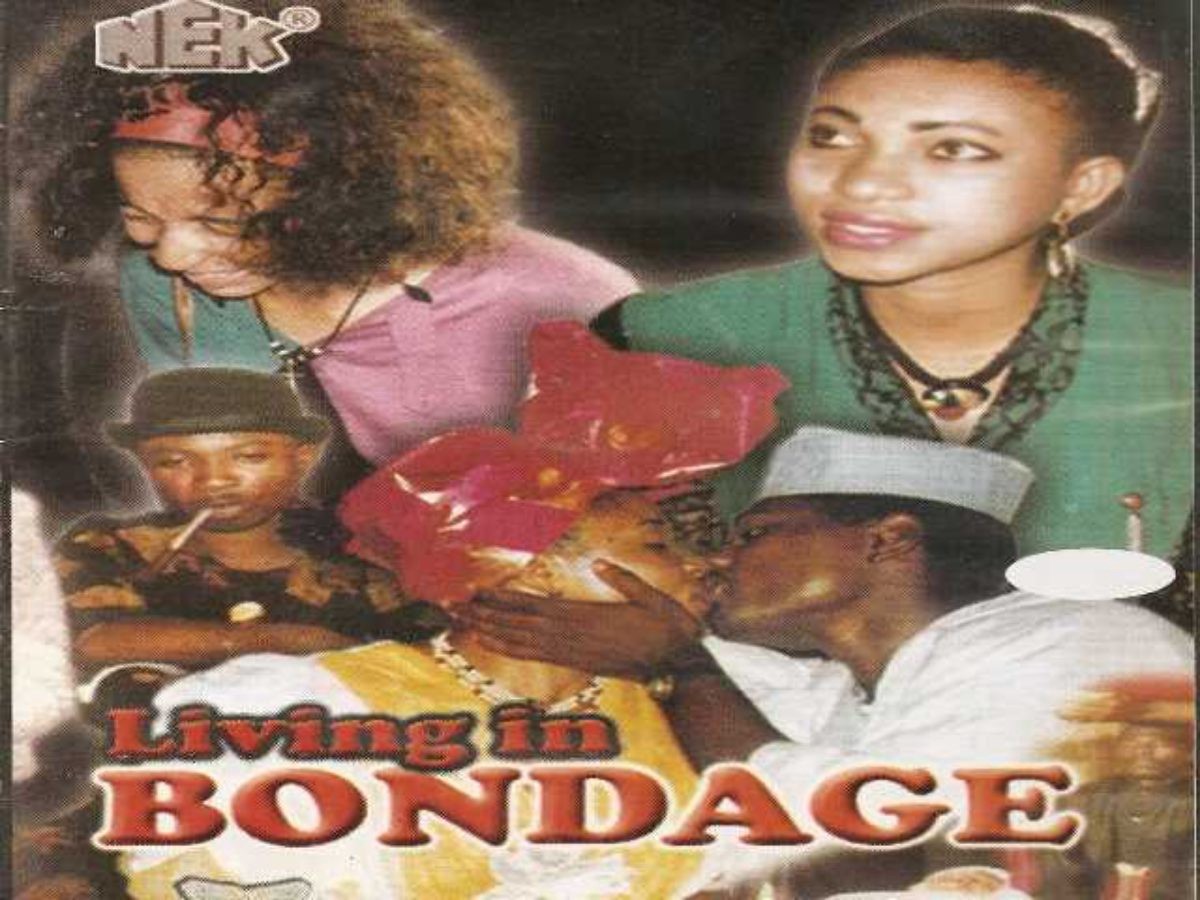

In 1992, the term “Nollywood”, a portmanteau of “Nigeria” and “Hollywood”, appeared for the first time in a global publication. It was used in a headline by New York Times journalist Norimitsu Onishi while reporting about the rise of Nigeria’s filmmaking industry. Whether he was the first to use the term is subject to debate. But his report about the industry in one of the world’s biggest publications signalled the coming of age of an industry that had been growing, in its own rights, for several decades.

Onishi, at the time, wrote, “Since the late 1990s, Nigerian movies have found a place next to offerings from Hollywood and Bollywood, Bombay’s equivalent, in the cities, towns and villages across English-speaking Africa. Though made on the cheap, with budgets of about only $15,000, Nigerian films have become huge hits, with stories, themes and faces familiar to other Africans. It is now, according to conservative estimates, a $45 million a year industry.”

Historically, film production in Nigeria was first overseen in the early 20th century by white colonialists and foreign filmmakers who wanted to create stories that their fellow countrymen could enjoy, regardless of who the actors were. Soon enough, after independence in 1960, the film industry began to gain popularity with locals, who also explored its opportunities. In the 1970s, powered by an economic boom fuelled by oil and foreign investments, more Nigerians started to invest in the industry, with film theatres sprouting in Lagos, showing a combination of local and international films.

[ad]

By the 1980s, cinema culture declined, and the audience started to favour direct-to-home options more. Films broadcasted on television began to gain popularity. This was the era when David Orere and crew brought “Things Fall Apart” to the screen via the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA).

In 1992, Chris Obi Rapu brought the classic “Living in Bondage” to life via video home system (VHS), and this marked the birth of Nollywood as we now know it. The migration from cinema to television and then direct-to-home is why Nigeria could export her stories via film to the rest of the world. From producing films exclusively for a local audience, Nollywood began to ship its stories out to other parts of Africa and the world. With time, the films and dramatisations of the Nigerian experience formed the basis through which outsiders understood and connected with the country and its culture.

Now, it’s not out of place to travel to other countries and have conversations with people whose assessment of Nigeria relies heavily on what they’ve seen in the films, especially in other African countries. Just as films from Hollywood and Bollywood have coloured the lenses through which several people see America and India, Nollywood has also impacted how people see Nigeria. Still, much of Nigeria’s cultural influence through film is limited to Africa.

According to film critic and consultant Oris Aigbokhaevbolo, “For Africa, it’s certainly true that what we’ve said about ourselves [in film] has contributed to how people see us. I don’t think it’s true for the rest of the world. I think that America, especially, has always had its own beliefs about the rest of the world and has stuck to them. They have their biases, and it’s going to be our duty now that there is some attention here to introduce them.”

To get to the next level, Aigbokhaevbolo says we need to get distribution right. Netflix offers an incredible platform for this, but there can be more. On the business end, we need to crack distribution. On the talent end, we need to crack [industry-wide] competence. “Can we make a series as engaging as Squid Game yet? From current evidence, I can’t confidently say we can. Although recent events such as the success of “Eyimofe (This Is My Desire)” at the Berlin International Film Festival and “Lizard” at the Sundance Film Festival awards show that we have the capacity,” he says.

[ad]

That said, Nigeria’s film industry has come a long way from Onishi’s estimation of its $45-million-size in 2002. Nigeria’s media and entertainment industry is one of the fastest-growing creative industries in the world, according to PwC’s Global Entertainment and Media Outlook for 2020-2024. The report also states that the industry has the potential to become Nigeria’s greatest export, contributing a projected annual growth rate of 8.6% and a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 19.3% from 2018 to 2023. The film industry isn’t the only one with this much potential. Music also does.

Music and culture

In June 2018, American rap legend, Lauryn Hill, listed Nigerian musicians Patoranking and Mr Eazi to perform alongside at the 20th-anniversary tour of her iconic album, “The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill”. This moment was a reflection of the upward trajectory of Nigerian music on the global stage. Two years earlier, Wizkid successfully broke into American music airways with his single, Ojuelegba, and subsequent performance on Drake’s One Dance. The latter earned Wizkid a Grammy nomination ahead of his eventual win in 2020 for “Best Music Video”.

In the same vein, Burna Boy was twice nominated in succeeding years, 2019 and 2020, for the Grammy Award’s Global Music Album category, which he won in 2020.

These awards are merely indicators of the spectacular rise of an industry that has been making waves for decades. The music industry’s success has significantly boosted the appreciation for Nigerian artists and culture worldwide.

In May 2018, Davido performed for a crowd of 10,000 people in the South American country, Suriname, much to his surprise.

The IMF projects that the music industry will generate an estimated revenue of $10.8 billion by 2023 and account for 1.4% of Nigeria’s GDP. So, there is a lot of potential here, both for local and international consumption. But even more so, there are opportunities to standardise the industry further, invest in more resources, and create platforms that allow more Nigerian artists to flourish.

[ad]

Technology and talent

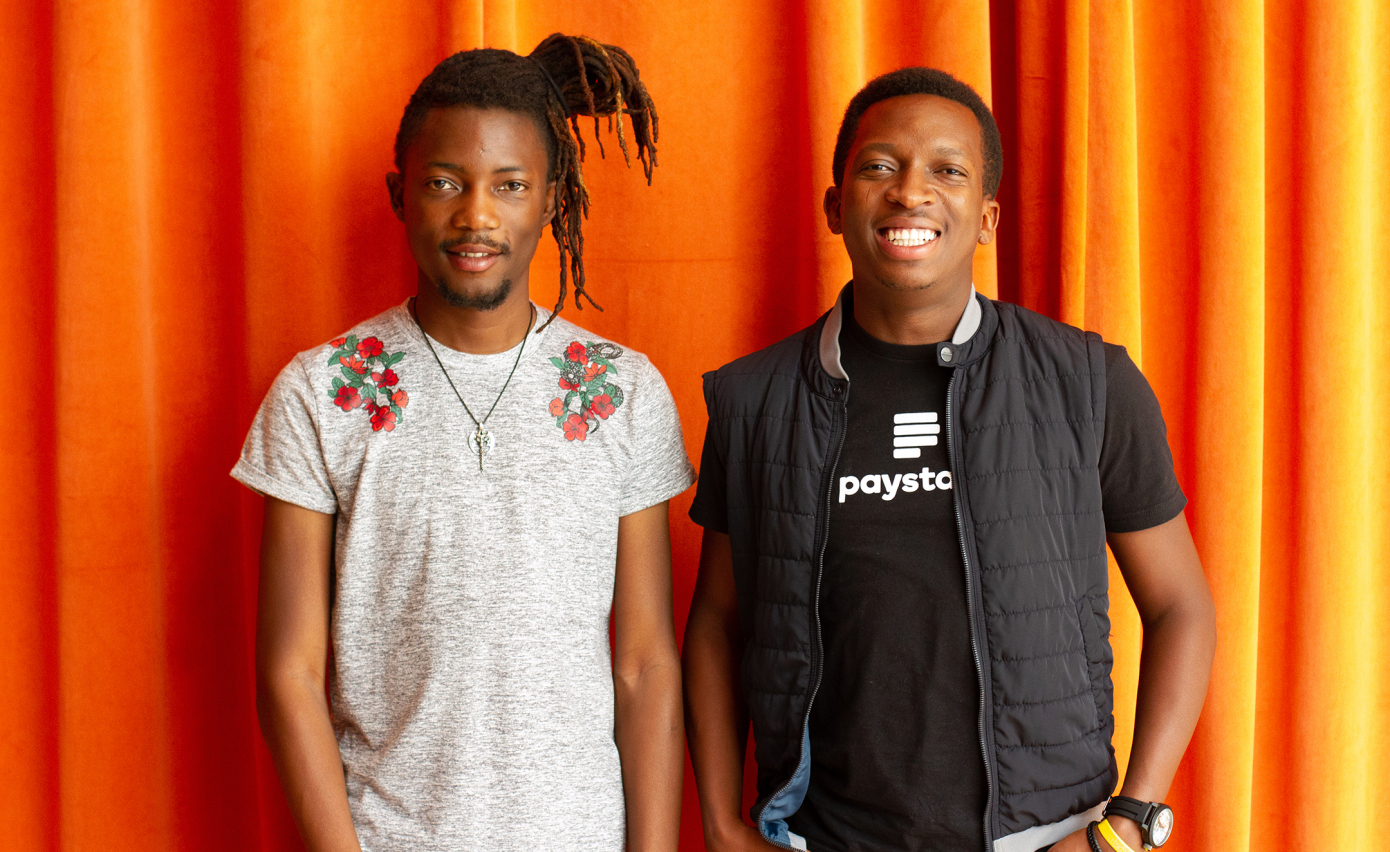

In 2020, Paystack, a Nigerian fintech company, got acquired by American fintech company Stripe for over $200 million. This marked one of the most significant exits for a startup up out of Africa. But more than that, it provided further validation for an ecosystem that most people outside it had mainly ignored for many years. Suddenly, everyone saw what was possible.

Since that announcement, billions of dollars in funding have gone into the technology ecosystem. The number of startup venture deals (above $1 million) rose from 25 in 2019 to 47 (and counting) in 2021, according to a report by Maxime Bayen and Max Cuvellier. This upturn reveals just how globally relevant Nigerian technology companies can be. The increased attention also spills into the quality of talent that the ecosystem both produces and attracts.

Several young Nigerians in the ecosystem have built their skills and networks up to the point where they can attract job offers from international firms, some of which offer them migration routes. On the other hand, many of these startups that have raised venture capital are hiring international experts to run their operations and help them scale. All of these create a net positive outcome for the country.

There is a lot more that Nigeria can offer the world and benefit from at the same time if it actively invests more in these assets. The beauty of all three — stories, culture, and talent — is that they are limitless and, unlike oil, will never be in danger of running out.

[ad unit=2]