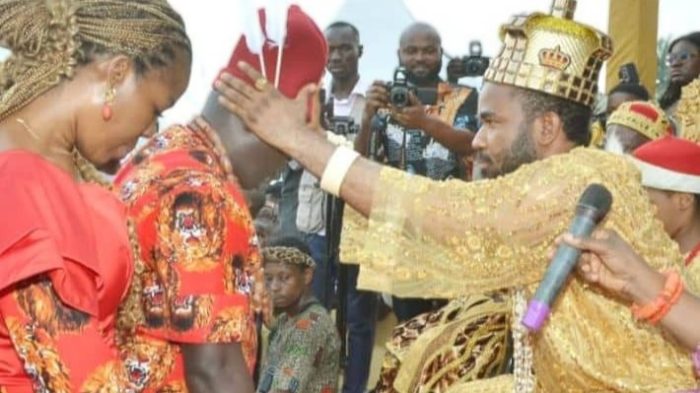

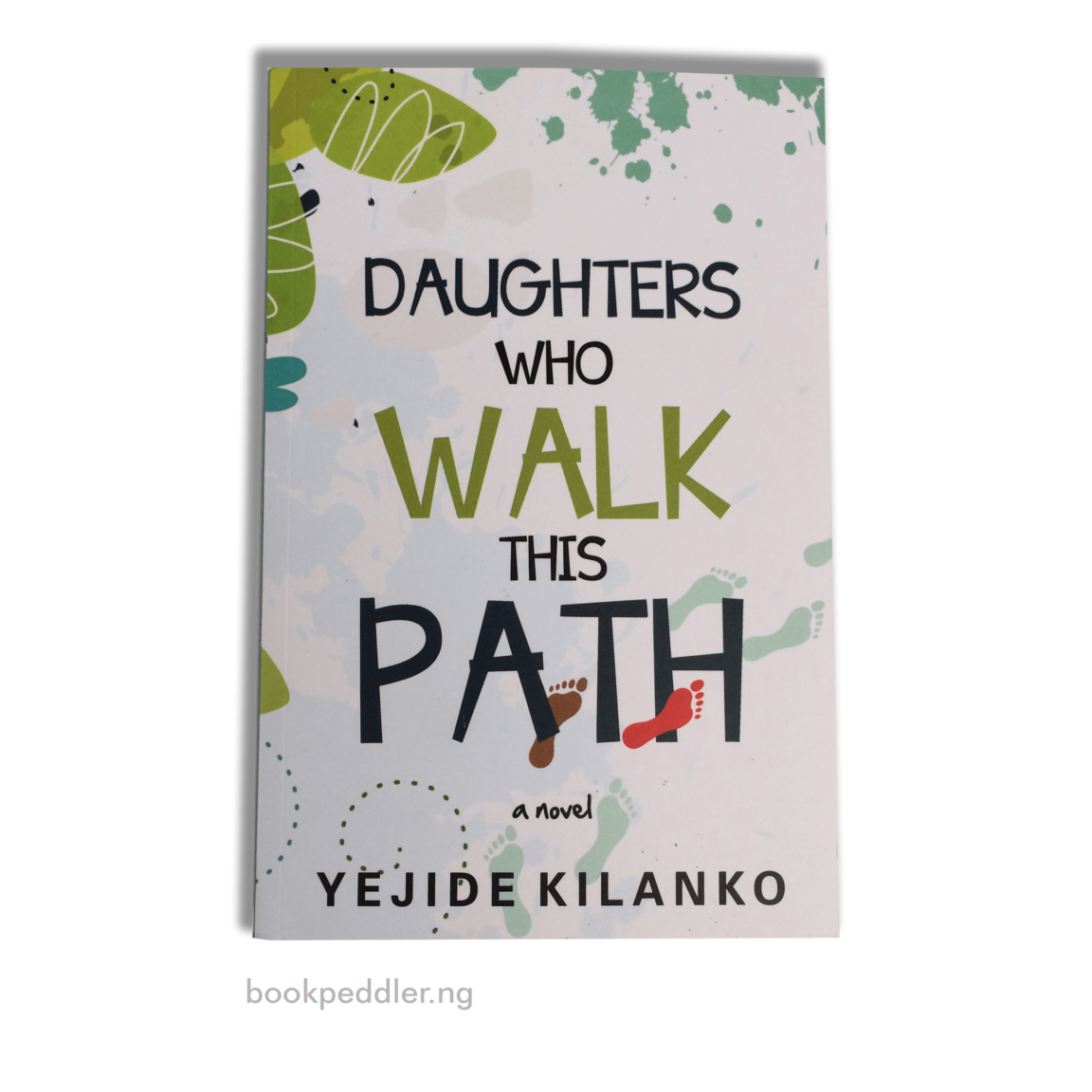

Yejide Kilanko became the voice of a generation and set an unexpected precedent for all Nigerian writers to come with the release of her globally acclaimed novel Daughters Who Walk This Path. Focusing on rape, sexual assault and coming of age as a woman in a hostile culture, Daughters Who Walk This Path shattered the shackles of silence surrounding Nigerian women and their roles in society, breaking boundaries and winning prizes.

Today, The Guardian Life talks to the brain behind the pen about womanhood, pilgrimages and why aspiring writers don’t exist.

How has being a woman impacted your writing?

It’s the only way I’ve walked through the world. It shapes my lived experiences which in turn impacts my writing.

Do you write what you see (real-life experiences) or do you write what you want (imagination and fantasy)?

It’s a mix of both. A real-life experience can spark an idea. My imagination then uses the experience as a building block.

If you could sit down with any famous writer, dead or alive, who would it be?

It would be a joy to have a sit-down conversation with Buchi Emecheta. Her book The Joys of Motherhood is one of my favourite books.

[ad]

What literary excursions have you undertaken to better your writing?

I love to travel. Each experience is a learning opportunity which enriches my writing. I do want to attend a writing residency in 2020. It’ll be great to step out of my busy daily life for a while.

What, in your opinion, are the worst and best aspects of the Nigerian publishing industry?

There is a lot to be said about the challenges Nigerians publishers face from high staff turnover, finding cost-effective ways of printing, dealing with ineffective book distribution channels, and fighting the menace of book piracy. These issues impact their authors.

The best aspect is that we still have courageous publishers offering homes to our stories. We need that. There’s nothing like having your people write and publish the stories which reflect your realities and dreams.

Does writing fill you up or drain you?

It does both. Writing is my pleasure and escape. On the days when I’m externalising emotions, or the characters are acting out, it’s a pain.

What are common traps for aspiring writers?

First of all, I don’t agree with the term ‘aspiring writer’. It’s either you are writing or not. For those looking forward to being published writers, I think it’s minimising how hard writing is and being unwilling to put in the work. Some writers are not open to or willing to learn from criticism. Some have over-inflated expectations. Whatever stage you are in your writing journey, self-evaluation is a good thing to practice.

Do you try more to be original or to give the people what they want?

It’s hard for me to write on demand. I see my writing as my way of offering a reader an invitation to my story world. It’s up to them to take the offer.

How did publishing your first book change your relationship and process with writing?

In some way, it validated my work which is a positive. I’m grateful for the relationships and opportunities publishing brought my way.

On the flip side, it stripped the anonymity I’d enjoyed. Now, people have expectations of me and my work. Thinking about whether I can meet those expectations causes me a great deal of anxiety.

What did you do with your first book salary?

I saved it. I’m a saver.

What period of your life do you take writing inspiration from most often?

For my debut novel Daughters Who Walk This Path, I did a lot travelling back to my childhood. For my recent books, I’m inspired by the now.

If there was one thing you had to give up to become a better writer, what would it be?

Overthinking. I would be much more focused if I didn’t question myself.

Why did you choose to write in this genre? If you write more than one, how do you balance them?

I started out writing poetry. Fiction came after. My mind wanders a lot, so I find it helpful to work on poems and stories at the same time.

Are there any popular misconceptions you think people have about your book?

With Daughters Who Walk This Path, I got several emails from readers who wanted to know if I’d experienced child sexual abuse. I’ve experienced some disbelief when I said no.

What did you find most useful and most destructive in learning to write?

I started writing at a young age. It gave my internal voices an external outlet. In terms of a negative, there are times when the uncertainty and doubt which comes with sharing my work increases my anxiety.

What do you think is the most powerful word in the English lexicon?

People ascribe power to different things. For me, in this season, it’s the word, ‘Enough’. The word evokes sufficiency, self-control, and boundary setting.

What’s the hardest scene you’ve ever written?

It was the final domestic violence scene in my novella Chasing Butterflies. A child was listening.

Why did you decide to focus on sexual assault?

I wrote Daughters Who Walk This Path because I was struggling with vicarious trauma from hearing stories of child sexual abuse. I had no idea that the book would spark the conversations it has.

Who are your favourite and least favourite characters of all the characters you’ve written?

A tough question. From my books, it’s Aunty Morenike from Daughters Who Walk This Path. Coco, a character from my short story, Real Estate Wars is not too far behind. My least favourite is Tomide from Chasing Butterflies. He made liking him hard.

Due to your novel Daughters Who Walk This Path focusing on women’s rights, some are critiquing it as feminist. Do you agree?

I do agree that it is a feminist book. I also see it as a compliment. And I identify as a feminist.

[ad unit=2]