The intersection between the Cybercrime Act and journalists’ rights to freely disseminate information is getting blurry, with the government allegedly leveraging the former to stifle rights to free speech of the latter. Recent arrests of journalists for cybercrimes have necessitated the need for proper demarcation between combating cybercrimes and rights of the Fourth Estate of the realm, AMEH OCHOJILA reports.

The balance between regulating online activities and safeguarding freedom of expression poses a serious challenge in Nigeria. The ‘prosecution’ of journalists under cyberbullying charges raises concerns about government overreach through the provisions of the Cybercrime Act, 2015. This legislation, akin to modern sedition laws, grants broad powers to monitor and control online content, which potentially stifles free speech.

For instance, the publisher of Cross River Watch, an online newspaper, Agba Jalingo, was arrested and charged with “conspiracy to cause unrest” after publishing a series of stories on financial accountability in Cross River. Another journalist, Olivia Fejiro, was arrested after publishing a story alleging corruption in Sterling Bank of Nigeria.

Also, a freelance journalist and broadcaster, Rotimi Jolayemi, was also detained for reciting a poem criticising former minister of Information and Culture, Lai Mohammed.

These cases illustrate the dilemma of journalists, who are often caught between the Cybercrime Act and their constitutional rights to freedom of expression and information. While the government has the responsibility to prevent and punish cybercrimes such as fraud, hacking, identity theft, cyberstalking and online harassment, it also has the obligation to respect and protect the rights of journalists to report on matters of public interest without fear of intimidation or reprisal.

According to the International Press Centre (IPC), a media rights organisation, the Cybercrime Act contains vague and ambiguous provisions that could be used to criminalise legitimate journalistic activities or dissenting opinions. For example, Section 24 of the Act prohibits cyberstalking and cyberbullying, which are defined as sending messages or posting statements that are “false, for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred, ill will or needless anxiety to another”. The IPC argues that this section is too broad and subjective, and could be used to silence critics or whistleblowers, who expose corruption or misconduct by public officials.

The IPC also notes that Section 38 of the Act empowers law enforcement agencies to access and intercept data from any computer system or network without a court order, which could violate the privacy and confidentiality of journalists and their sources. The IPC calls for a review and amendment of the Cybercrime Act to ensure that it is consistent with international standards on freedom of expression and information, and that it does not infringe on the rights of journalists and other online users.

The Nigerian Union of Journalists (NUJ) also urges the government to respect the role of journalists as watchdogs of democracy and ensure their safety and security. The NUJ advises journalists to comply with the ethical standards of their profession and avoid publishing false or defamatory information that could harm the reputation or dignity of others. The NUJ also encourages journalists to seek legal advice and assistance when faced with charges or threats under the Cybercrime Act or any other law.

The trial of journalists under cybercrime charges is a reminder of the need to strike a balance between combating online crimes and respecting peoples’ rights. The government should ensure that the Cybercrime Act is not used as a tool to suppress dissent or censor information that is in the public interest. The journalists should also ensure that they adhere to the principles of accuracy, fairness and accountability in their work. Only then can both parties contribute to a healthy and vibrant online space that fosters democracy and development in Nigeria.

Section 24(1) of the Cybercrime Act, 2015 reads: “A person who knowingly or intentionally sends a message or other matter by means of computer systems or network that is grossly offensive, pornographic or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character or causes any such message or matter to be sent, or he knows to be false, for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred, ill will or needless anxiety to another or causes such a message to be sent, commits an offence under this Act and is liable on conviction to a fine of not more than N7million or imprisonment for a term, not more than three years or both.”

Interestingly, section 39 of the 1999 Constitution provides that: “(1) every person shall be entitled to freedom of expression, including freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart ideas and information without interference.”

However, Section 45 of the 1999 Constitution provides: “(1) Nothing in sections 37, 38, 39, 40 and 41 of this Constitution, shall invalidate any law that is reasonably justified in a democratic society in the interest of defence, public safety, public order, public morality or public health; or for the purpose of protecting the rights and freedom of other persons.”

While the government argues for the necessity to maintain public order and safety, international bodies like the ECOWAS Court of Justice have deemed certain provisions incompatible with human rights standards. Calls for the repeal of the Cybercrime Act or its amendment reflect widespread concerns among legal experts, journalists and activists.

Presiding Justice of the ECOWAS court, Justice Keikura Bangura, in a recent judgment asserted that section 24 of the Cybercrime Act does not conform with Articles 9 of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) and Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Both covenants promote free speech and Nigeria is signatory to them.

Globally, digital rights abuse remains one of the biggest issues facing journalists, activists, and political dissidents. They are more likely to be arrested and detained for alleged violation of digital and internet laws. They also face a high rate of digital harassment and cyberbullying, and are also primary targets of extra-legal cybersurveillance.

Critics argue that the Cybercrime Act contains subjective language and lack of clear definitions. According to them, it undermines constitutional protections of freedom of expression. The Act’s enforcement, which is devoid of safeguards, risks arbitrary application and stifling of dissenting voices and undermining democratic principles.

According to Mr Tayo Oyetibo (SAN), the supremacy of the constitution over every other law is an immutable principle of Nigerian law derived from the provisions of section 1(3) of the constitution itself. In creating criminal offences, he noted that section 24(1) of the Cybercrimes Act uses words that are entirely subjective in meaning to describe the actus reus elements of the offences, despite the fact that the actus reus of an offence ought to be objective and not subjective in definition.

“Worse still, the Cybercrimes Act makes no effort to give certainty to the meanings of any of the words used in its section 24(1) by defining them anywhere in the Act, which means that only judicial definitions can be given to those words in any case where a person is charged with an offence under section 24(1) of the Act.

“In the context of the constitutionally guaranteed right of citizens to freedom of speech under the Nigerian constitution, there is the pressing question of whether the Cybercrime Act is fit for purpose pursuant to which it was enacted, particularly in view of the provisions of its section 24(1).

“It would appear that the answer to this poser is in the negative, which means that it is imperative for deliberate steps to be taken to remedy the situation, particularly against the backdrop of widespread complaints against the deliberate misuse and abuse of the Cybercrimes Act against certain categories of persons in Nigeria,” he pointed out.

He argued that it is not a matter in which long winding technical recommendations are necessary. The simple recommendation, he said, is that section 24(1) be entirely deleted from the Cybercrimes Act, due to its apparent irreconcilability with the provisions of section 36(12) and 39(1) of the constitution.

In light of these challenges, stakeholders argued that meaningful reform is imperative to strike a balance between combating cybercrime and upholding fundamental rights. As Nigeria navigates this delicate balance, ensuring that legal frameworks respect constitutionally guaranteed free speech is paramount to safeguarding democracy and fostering a vibrant media landscape.

This no doubt brings to fore the need to enlighten journalists on responsible reporting, including ethical considerations, fact-checking, and respecting individuals’ privacy and dignity. Striking a balance between these two aspects is essential for maintaining a free and responsible press in society..

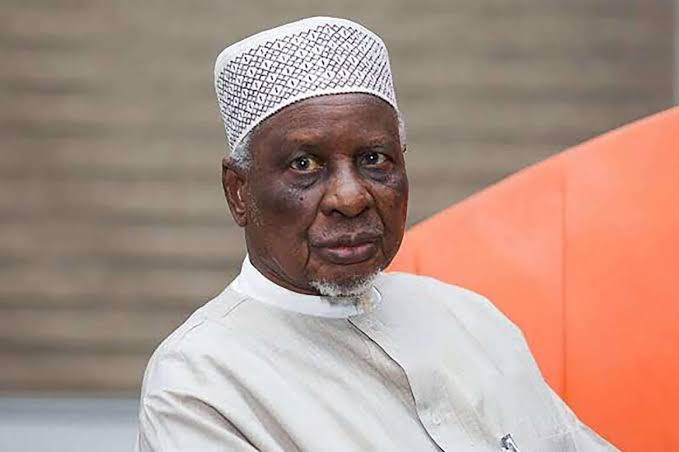

However, the Administrator of the National Judiciary Institute (NJI), Justice Salisu Garba Abdullahi wants journalists to always be fair and balanced in reportage of all judicial proceedings and decisions to sustain the ethical standard of all judicial matters in the country.

He said in doing so journalists are building a reputation for themselves and the media houses they represent. A Lagos based lawyer, Paul Mgbeoma stated that there is in recent times, a pattern suggesting that law enforcement agencies wrongly use the provisions of the Cybercrime Act to intimidate not just journalists but activists and people who hold views that are not palatable to powers that be whether in government or private sector.

“What in my opinion is needed is for the law enforcement agencies and prosecutorial authorities to be properly trained to understand the contents and essence of the Cybercrime Act. It needs to be made clear that it is not just that journalists are not ethical about the practice of their profession,” he declared.

He said prosecutorial authorities must also learn to strike a balance between the right to freedom of speech and expression as contained in Section 39 of the 1999 Constitution in the enforcement of provisions of the Cybercrime Act.

For Akintayo Balogun, a lawyer, an examination of the Cybercime Act, cyberstalking as provided for in Section 15 of the Act could be used against journalists. The section, he said, also provides for punishment for anyone found guilty.

“In my opinion, the section is perfectly in order and would quell activities of persons who involve themselves in peddling false information. Journalists, particularly, internet based journalists, freelance writers and investigative journalists that have little or nothing to do with paper prints are mostly culpable in this provision of the Act.

“Many times, they write not really because they want to carry the proper news but to create traffic on their blogs. This desperation by bloggers makes them publish whatever would sell and not necessarily what is right. As a lawyer, I can state categorically that there are several reports online that are inaccurate, malicious, deceptive and vindictive,” he stated, adding that the Act is in order and should be used to effectively curb cyberstalking.