Aeons back in strategy class at business school, my study group would often assess the militaristic provenance of the concept of “strategy” whilst debating whether leadership was innate or teachable.

As with everything in life, opinions differed on the latter, with cogent justifications too. I played a straight bat on this issue adopting the view that whilst aspects of leadership could be learned, for instance, strategy, human resources management, business process reengineering; programme, project and portfolio management, finance, organisational development skills, operational management; the important and esoteric skills of creativity, innovation and strategic foresight could not be learned.

My view then, and now, is that those skills are innate; you either have them or you don’t. Did anyone teach Steve Jobs and his Apple team to make an iPhone say?!

Thus, the foundational premise is that leadership of any kind, of necessity, implies self-leadership. That means understanding oneself, strategic insights, content knowledge and contextual understanding. It entails self-discipline, a high degree of emotional intelligence and cultural awareness. How can one lead others without leading oneself?! The expression “physician, heal thyself” in the book of Luke, chapter 4 at verse 23 resonates.

That segues into the extant subject matter of adaptive leadership. This analysis seeks to examine the what, how, wherefores and practical relevance in the corporate, national and international contexts. Of what gain is adaptive leadership when isolated from robust institutions and sustainable legacies? Leadership, whether narrowly or widely defined, inescapably implies followership. How might the followership and cultural relativities thereof impact the concept of adaptive leadership? These are all huge arresting questions.

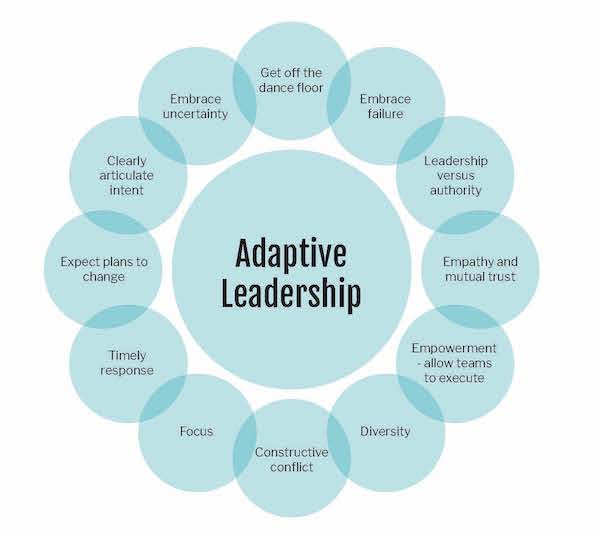

Originally developed by Harvard University academics Professor Ronald Heifetz and Marty Linsky, adaptive leadership is “the practice of mobilizing people to tackle tough challenges and thrive”.

As deducible from the concept, adaptive leadership is one which not only recognises the dynamic challenges corporates, and by extension, regions and sovereign nations, encounter like corporate insolvency, shareholders’ revolt, fiscal policy reversals, pandemics or, in extremis, war; entailing, inter alia, increasing economic and socio-political volatilities, uncertainties, complexities and ambiguities (VUCA) or worse.

Adaptive leadership theory reinforces the view that creativity and innovation, the willingness to take considered risks and shared decision-making are all essential ingredients for confronting complex challenges and problems as the context demands.

Fundamental principles which underpin adaptive leadership include: a.) Emotional intelligence (the empathic capacity to handle cultural relativities, interpersonal and situational contexts sensitively); b) Organisational justice (this implies embedding a culture of integrity and honesty); c.) Iterative development (the ability and willingness to learn and apply new learning); and d.) Character adaptive leadership (which implies creativity, transparency and a high degree of honesty).

The model seeks to analyse, interpose and debunk the orthodoxy of staid practices through innovation, as a mechanism of establishing core competencies which adhere closely to organisational or national strategic priorities.

Adaptive leadership rests on 3 formidable pillars:

Sharp prioritisation: It is an immutable truth that no one person, organisation nor a sovereign nation can do everything it wishes to do all of the time independently. That capacity just does not exist hence the imperative of mutual interdependencies across external supply chains, operations, internal value chains and international boundaries. This truism in adaptive leadership is manifested in the abstraction of activities, processes and systems which add little or no real value to seminal orga

For example, an entity may decide to automate its HR and Finance functions thereby reducing overheads. Likewise, a country may opt to invest in robotic military hardware and drone technology, strategically nixing troop numbers and potential casualties in conflict yet, securing gaining a significant advantage in military superiority over enemy forces. So, sharp prioritisation opens opportunities for competitive advantage, economic gains and technological optimisation.

Analysis and prudent risk management: The management guru Peter Drucker’s observation “you can’t manage what you can’t measure” holds true here in that adaptive leadership emphasises effective qualitative and quantitative research, evaluation and testing as the basis for taking calculated risks. In other words, a degree of “experimentation” is permissible if the end result would justify the gains.

To illustrate, 3 US firms alone, Alphabet, Apple and Tesla with a combined 2021 turnover of USD 618 billion (more than the combined 2021 GDP of Ghana, Gabon and South Africa USD 515.86billon!); deploying robust forensic analysis, artificial intelligence, market foresight on consumer psychology, demand patterns, demographic trends and measured risk-taking, have completely disrupted technology ecosystems to the benefit of consumers across all continents. These encapsulate the realms of autonomous driving, data analysis, cyberbanking, the internet of things (IoT), interoperable media, mobile telephony, and space technology to name a few. These firms have embedded adaptive leadership models in their practices and efficient operational processes.

Continuous improvement culture: The essence of research, evaluation and prudent risk management are that the acquired new learning, innovation and operational gains can be optimised and incorporated into product life cycles and a corporate’s organisational modus operandi: with a view to maximising shareholder value or service delivery for citizens and taxpayers. Beyond the corporate context, adaptive leadership is applicable in a national and global context.

The logic is straightforward too. Corporations are, in one sense, mini “sovereign nations” That’s because although the complexities and demographics may well vary in quantum, nevertheless, the challenges of effective service delivery, optimising value for corporate citizens (and taxpayers!), effective financial stewardship, managing conflicting internal and external interests, and policy trade-offs on cross-cutting issues in the corporate (and national) interest are not necessarily dissimilar all of the time.

The inference being drawn is that adaptive leadership affords the capacity for skills transfer in a variety of contexts. For example, successful entrepreneurs have deployed adaptive leadership strategies including a clear vision of transformational change; strategic thinking, emotional intelligence, proactive stakeholder engagement, and to a greater or lesser degree, cultural empathy; evidenced -based policy development, a willingness to take risks and innovative adoption of technology and their entrepreneurial flair, in their transition to high political office.

Pertinent examples include Michael Bloomberg, the American billionaire and founder of Bloomberg LP, who served 3 terms (2002- 2013) as New York Mayor; Sebastian Pinera, Chilean billionaire entrepreneur who served 2 Presidential terms (2010-2014; 2018-2022); Herman Mashaba, South African millionaire entrepreneur, who served as Johannesburg Mayor (2016-2019). Regarding robust institutions and sustainable legacies, the argument is that the cited entrepreneurs turned politicians, applying adaptive leadership principles, contributed to the development of enduring institutions. In Bloomberg’s case, he built his business from scratch and the firm’s revenue in 2021 was USD 10 billion.

In of itself, adaptive leadership cannot exist in a vacuum. In other words, a leader must lead a natural person, corporation, an institution, a country or blocs of countries, or indeed a combination. And where there is a leader, there must be a follower, as a function of deductive reasoning.

Extending the logic, “follower” implies, as the context justifies, consumers, employees, the electorate, shareholders, followers, and national and international citizens. The hypothesis being advocated, therefore, is that whether at the corporate, national or international level, there is a compelling case for a well-informed, engaged and switched-on stakeholder base.

The reasoning is that it is not enough to criticize an adaptive leader, especially where the relevant “follower” has failed to: proactively hold the said leader to account; responsibly exercise his rights and corresponding responsibilities by, for example, delivering personal and business objectives; exercise civic responsibilities; make or facilitate innovation which can positively transform an entity’s fortunes and estimation by local and international stakeholders.

Then again, there cannot be a one size fits all adaptive strategy. The context matters. Culture matters. The sub-culture matters. In short, there is no homogeneity in organisational, national and global settings. On the contrary, heterogeneity reigns supreme in different situational contexts. Therefore, adaptive leadership strategies of necessity, and nomenclature, have to be amenable to dynamic change focusing on key strategic organisational and national priorities.

The US Army in ADP 6-22, 2019 sums it all up neatly: “Leadership is the process of influencing people by providing purpose, direction and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organisation”.

‘Ojumu Esq is the principal partner, of Balliol Myers LP, a firm of legal practitioners based in Lagos, Nigeria.