How do you know when an economy is industrially deficient? Well, one of the easiest ways is by looking at the content of the country’s import and export baskets. This is more than the balance of trade. It is about what the country actually buys and sells.

[ad]

Strikingly, it is very difficult for a country to have a positive balance of trade while being industrially backward. To do this, a country will have to sell a certain amount of what other countries need and buy less than this amount from them.

For this reason, most countries prefer to produce some of what they consume so that they need to buy less from others, and to add value to the things they sell so that they need fewer units to make more money. To achieve this, a country needs a strong industrial sector.

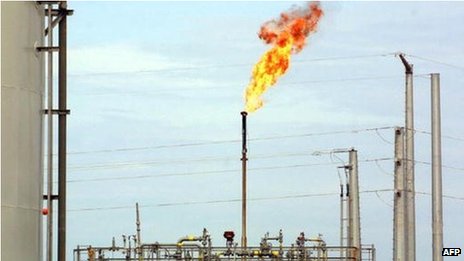

Presently, Nigeria is unable to do either of these things simply because its industrial sector is weak. The country exports crude oil and imports finished petroleum products. It exports cocoa beans and import chocolate. And so on. Little wonder then, that the country has serious debt and foreign exchange problems.

Recently, an economist and banker who works for the government was quoted as saying that Nigeria’s foreign reserves position is lower than the market capitalization of the three top South African banks.

The Debt Management Office (DMO) also reportedly claimed that the country spent 2.34 trillion naira on debt servicing within the first half of 2023. That’s more than $3 billion US dollars, about 5% of Ghana’s GDP in 2022.

Given these conditions, what needs to be done for Nigeria to reverse its industrial fortunes? Fortunately, we have answers from several decades of research on industrial policy and development. Several countries in East Asia have managed to go from backward to frontier industrial economies and there are lessons to learn from them.

These countries share three attributes: i) a high rate of fixed investment; ii) high manufacturing contribution to GDP, which is directly associated with a large share of industrial employment; and iii) a consistent rise in the share of manufactured exports. In Nigeria’s industrial glory days, it was exceptional in all of these areas.

[ad]

For instance, the Cotton, Textile and Garments (CTG) sector in Nigeria in the 70-80s used to employ over a million people. Today, the CTG sector is literally dead, and Nigerians now import local fabric, including Ankara and Aso-oke from China.

The production of goods and services requires a considerable amount of fixed assets (such as plants, machinery, equipment), basic infrastructure (such as roads, railways and ports), and constructed spaces (such as schools, hospitals, and residential, commercial and industrial buildings).

The cost of providing these inputs is reflected in gross fixed capital formation as a share of GDP (GFCF). Forty-one years ago in 1982, Nigeria’s GFCF was 86 percent, far higher than the average of 31 percent in East Asia. By 2021, Nigeria’s GFCF had fallen to 35 percent, the same level as East Asia. Nigeria’s low and declining fixed investment has precipitated an acute infrastructure deficit.

The strength of the industrial sector in a country or region manifests partly through the contribution of manufacturing to total domestic production and export. For every Nigerian citizen in 2022, manufacturing contributed only a mere US$66.8 to GDP. Moreover, only 6 percent of all exports from Nigeria in 2021 was manufactured, the rest was mainly crude oil and primary commodities. This is a far cry from an average of 84 percent across East Asian countries.

One of the ways manufacturing contributes to GDP is through employment. In 2021, industry accounted for just 13 percent of total employment in Nigeria in contrast to 26 percent in East Asia. In other words, while at least one out of every four employed East Asian worked in the industrial sector, only one in ten employees in Nigeria did.

These numbers are just symptoms of a major dysfunction in the country’s industry. When companies are dead, inactive or continually struggle for survival, they cannot produce anything let alone employ people.

Nonetheless, Nigeria has the potential to revitalise its industries and build a more prosperous future. By addressing the above areas, it can unlock the strength of its industrial sector, create jobs, and reduce dependence on imports. This is the most sustainable path to economic growth and stability that can benefit all Nigerians.

Egbetokun is senior Lecturer in Business Management, Leicester Castle Business School, De Montfort University, Leicester, United Kingdom. aaegbetokun@gmail.com

[ad]