Suddenly, in 10 years, Freedom Park, located on Broad Street, Lagos Island, has become a cultural icon. It has garnered fame and adoration. The kind of fame you only see in countries of Europe and America with great facilities.

The story of the facility could be traced to a quiet moment in 1998 when a group of architects got together under the aegis of CIA (Creative Intelligence Agency). This was like young firms around who had a creative outlook on architecture.

“We wanted to challenge ourselves on how we could improve things around Lagos, especially with the Millennium coming and different countries doing one project or the other all over the world. We thought about how we could put together our own ideas and submit to the government,” said Theo Lawson this hot afternoon, as he cranked up the story of the facility.

Different firms came up with their own proposals. A particular firm designed a transportation interchange at CMS, where you could have water, bus, and helicopter transportation exchange. Some firms went to traffic management.

“We actually sent students out to study the traffic, design okada lanes and re-route traffic around Lagos,” revealed Lawson.

He said, “I wanted to create a park because I felt Lagos needed breathing space and I knew this space existed. I always thought it would be a shame if we lost this space to high-rise buildings. So, I put that as my proposal to evolve the park. During the process of the research, we invited students to come along, so, it could be like a training exercise on how to develop ideas and projects.”

His story was like a notebook with every event a blank page that opened the park to more insights. He began what seemed a journal entry of the making of Freedom Park.

Designed by Lawson, the Park was constructed to preserve the history and cultural heritage of Nigerians and mark Nigeria’s 50th-anniversary independence celebration in October 2010.

It is under the management of LORK Enterprises LLP comprising Total Consult Ltd, Arc. Theo Lawson, Femi Odugbemi, Sewa Kpotie (deceased) and Iyabo Aboaba who have over the years developed and expanded the ethos of the centre to what is today a most celebrated arts and culture space in Nigeria and beyond.

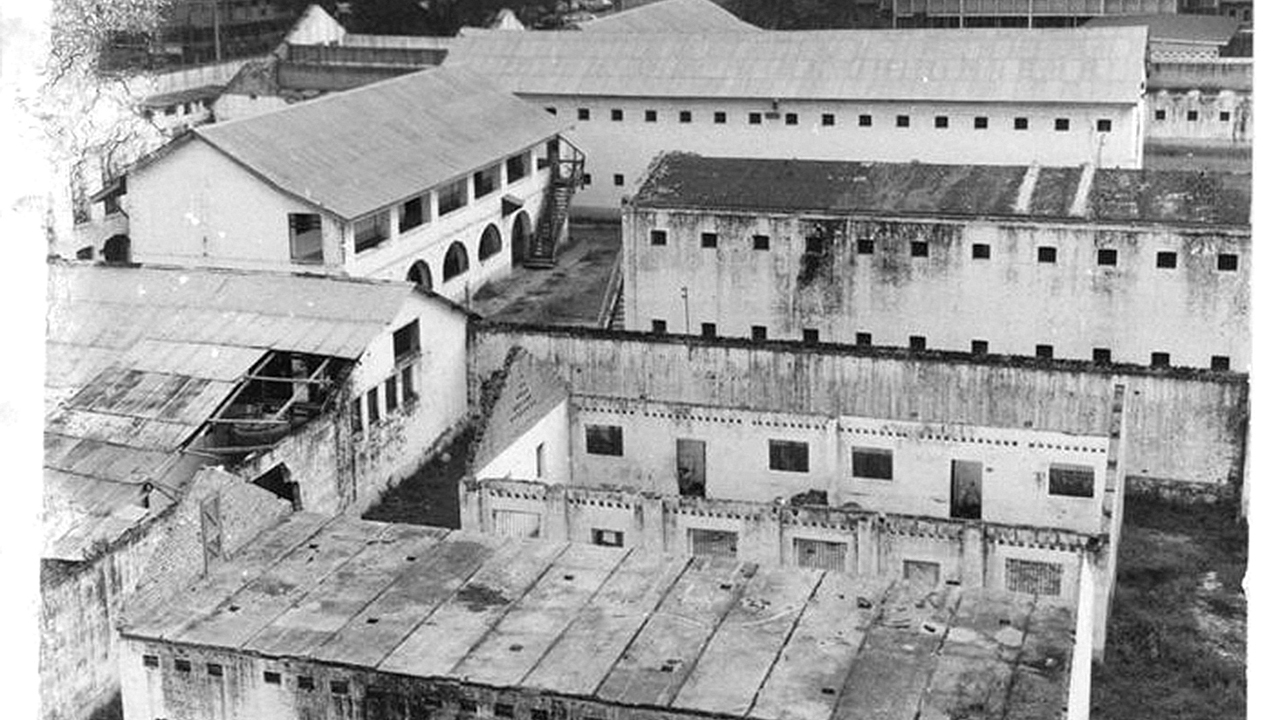

The need for a formal system of law when the government passed the prison ordinance that introduced their own concept of criminal justice to the colony to keep order and protect their interests.

A penal system, needing a prison, was then constructed in 1872 in the form of mud walls and grass thatch, initially with the design to hold 20 prisoners, but it did not last long because of British colonialism in Lagos “kept throwing fire into it and setting it ablaze, and so then, in 1885, the colonial government imported bricks from England and rebuilt the prison.”

[a]d

Broad Street Prison was then rebuilt with £16,000 and in 1898, 676 males, 26 females, and 11 juveniles were imprisoned at Broad Street prison in just that year, according to the colonial reports.

In the years leading to Nigeria’s independence, the prison was a Maximum Security prison where political prisoners were kept. By the time Nigeria got her independence in 1960, Lagos had been under British rule for 100 years. And throughout its period of use from 1885, the Broad Street Prisons — Her Majesty’s Broad Street Prison — held some of Nigeria’s foremost activists and nationalists such as, Herbert Macaulay, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Lateef Jakande and Michael Imoudu who all served time there at one point or the other due to their political beliefs and activism.

While some of the activists were held in the prison before Nigeria’s independence in 1960, Awolowo was incarcerated in the 52-cell facility while standing trial for treasonable felony.

It was closed in 1972. It was eventually reduced to a dumping ground until the 1990s when plans were drawn up to transform the site into a creative space.

The former records office was turned into a museum complex and the old prison block was converted into a food court, built as a replica of the tiny prison blocks.

The 52 cells in the facility have been ‘intentionally preserved ‘ to remind visitors of the memory on incarceration, which ultimately resulted in freedom.

In ensuring that the facility retains the relics of the colonial masters’ style of oppression, the gallows, on which condemned prisoners were hanged, still adorn one of the apartments in the complex.

DURING the course of visiting the site, Lawson and his team met somebody on the street who is one of the coffin makers around. They were just walking around when he asked who they were looking for because they were taking pictures.

“We said we were doing a project here and everything. The man used to work here. He was a welder at one time, so, we asked him to take us inside. He took us in through the gate area. It was a squatter’s camp then — a refuse dump. It had stories about Awolowo, Esther Johnson and all sorts of interesting stories, and we felt that this is not just going to be a park, there’s history to it and it had to be more of a memorial than just a park. So, that was where the idea of Freedom Park came about. It was a hundred years of prison, from 1872 to 1972. So, the whole history of this place is still buried within the site here. We felt it was a very strong thing that should be proposed and pushed very aggressively. Let’s see if it would become another apartment building. All the ideas were compiled and submitted to the government, then in 1999, and a lot of people put pressure on it, but nothing came out of it and we all forgot about the projects and even CIA went to bed because everybody got tired. It was a good exercise for all it was worth.”

Ten years later, in 2008, Lawson got talking with someone, who facilitated a meeting with Gov. Babatunde Fashola at the time. She happened to be one of his advisers. She asked if Lawson still had any drawing or synopsis of what CIA planned then, so, “I found the synopsis we did years ago and I sent it to her by email and she shared it with Fashola and she called me back and said, ‘the governor says when can I come for a presentation?’,” Lawson explained.

Three weeks later, he found the models, did some additional cleanup on everything and some slides for the presentation — talking about the history of Lagos and how this prison came about. By the time it was presented to Fashola, he had seen the whole thing played out in his mind. The governor had done most of the work, and it showed he was very interested in the project.

From the approval time to the signing of the contract, it took three months before the team got mobilised to start. Those three months he had hoped would be used to do archeological dig around the site to find out what was buried there.

“First of all, don’t forget, the site had been a refuse dump for almost 30 years from 1972 when it was shut down. In 1972 when it was shut down, they had different developers that had come out long with ideas, we actually allocated portions of the site to different developers but because of the history of crews, crew after crew after the crew, we all lost the deposit,” he said.

When they came on site, there were lots of abandoned equipment and a lot of refuse, so, the team spent the first few months trying to gather all of that and that’s the three months after waiting for the mobilisation, another three months evacuating refuse, but the governor said timing was not on their side anymore. “We needed to deliver the project sooner because he wanted to make it an anniversary project. The official delivery date was supposed to be March the following year, but we shortened the period to deliver for October, it now became a rush project. We had to rush everything and we couldn’t excavate anymore. Anything we found along the way, we kept and that’s what we have in the museum today,” Lawson said. “Freedom Park came after 10 years from the concept, and it taught me one thing that patience is a virtue. Every good idea has its time. Incidentally, the Kuti Memorial House in Abeokuta also took another nine-year hiatus. From the first time, we pitched the idea to; I think it was Gbenga Daniels’ time then, all the way to the end of Amosun’s period, so it was like a rush job. “

Many works of art commissioned by the Omooba Yemi Shyllon Foundation dot the park. The works are statues painted black with fiberglass as the medium. They are almost life-size statues that capture the Nigerian way of life from different ethnic groups in the country.

With its open-air and indoor facilities, the Freedom Park has become a great place to hang out with friends for food and drink as well as a rendezvous for the literary inclined individuals. It is a place of art and a piece of work; a true tourist attraction in Lagos, Nigeria.

With Nobel laureate Prof. Wole Soyinka as principal patron and trustee, as well as the Omooba Yemisi Shyllon sculpture garden, the credibility and reputation of the park remain incontestable. It has managed to dispel the long-held phobia of visiting Lagos Island and the fear of ‘area boys’.

In 2015, it was awarded the Trip Advisor Certificate of Excellence and is listed on most tourist sites as a must-visit when in Lagos.

Recently, it became home to the Society of Nigerian Artists (SNA), also hosting monthly meetings and other social events of the Nigerian Institute of Architects (Lagos Chapter).

It is host to over 12 arts and culture versed festivals in a year; stages monthly performances, visual art exhibitions, and boasts of live music performances at least once or twice weekly.

Freedom Park is not elitist and encourages interaction across social and professional strata. It promotes a democratic space where freedom of expression is entrenched in our charter. It, however, strives to ensure the safety and comfort of all guests.

“It is an irony, the paradox of that conversion into a place of creativity, of the imagination of excitement, a corner for children, just converting restrain into freedom,” Prof. Wole Soyinka Noble Laureate for Literature.

Fashola said at the commissioning that, “taking into account our history and aspirations, this park represents a journey towards a greater goal, the triumph of humanity over all forms of tyranny, both political and social, and the ultimate liberation of the human spirit from all that seeks to confine it.

“It is a testimony that points to our administration’s commitment and believes in freedom as the essential purpose of governance- freedom from need, freedom from poverty and its many spin-offs, and the freedom from insecurity.”

But it has not been a smooth ride making the park. When Lawson and his team had a meeting with the Public-Private Partnership board-led by Ayo Gbeleyi, they came up with a proposal that did not favour. The park was asked to deliver 25 per cent of profit IN the first year, second and third year 45 per cent, fourth and fifth year 50 per cent of gross of N50 million under or higher. “We said this is not practical. We said let’s go ahead and try this first. Why don’t you make it percentage of profit? They said no they don’t want it to put any staff here. They said we should go ahead, but make sure we deliver some gross.”

Partly on the contract, after year two, it was believed that they would evaluate the arrangement to see whether it was possible or not. Unfortunately, there was a change in government and commissioners.

“During Mr. Oladisun Holloway’s time, we had the Black Heritage Festival, which brought a lot of events at Freedom Park. During Akinwunmi Ambode’s tenure, things changed. Everything went to Eko Hotel or Eko Atlantic City and other places like Terra Kulture. Nothing was brought to Freedom Park, which was a government partnership. We had to struggle and I guess we are still struggling. We had to pay 25 per cent gross. We kept on asking for that meeting for review, but subsequent commissioners wouldn’t take any decision like that because they were not present at the initial negotiation and they didn’t want to go into any change of contract,” he said. “We, as partners, are not making any money. I work here, my office is here as an architect, so, basically, my job keeps me occupied. What we have done over the period of time is to try to establish Freedom Park and get over the stigma of people who were afraid to come to Lagos Island because of area boys. Over the years, we have been able to establish Freedom Park as a safe place to visit.”

Arts and culture workers believe that the facility would have enjoyed if there were a National Endowment for the Arts. Championing this is the actress Tariah Tom-West. She told The Guardian, “there are no art centres in the world that make a profit. They depend on a grant given to them by foundations and special endowment by government.”

A lot of people come to this place to spend time due to heavy traffic. So, during the week, there are lots of captive audiences. “I think we have been able to create content for them to feel comfortable while they are here. Most of our customers are white-collar workers like banks, lawyers, doctors etc. and off course we have the art community. Over the year, we have about 10 and 15 festivals. We have more than met our obligation to the arts community. We also have international festivals, music and regular theatre performances, art exhibitions, book readings, poetry reading and spoken words, “ said Lawson. “We cannot charge N5000 or N10000 as gate fee here. We will not have an audience unless a big artist is featured, but that’s not what we are about. We are about building talents from the ground up and I think one of the biggest problems we have in the arts community is the corporate manager who looks for ambassadors in so-called hyped artist and they all recycle the same people over and over again without looking for ways to build up new talents.”

Lawson believes that giving N80 million is not okay; as such an amount can be spent to establish performance centres. “We have a problem in Lagos Island. Most of the youths are unemployed and all they do is hang around. Rather than stay in the Island where the whole place is congested, 15 to a room, walking around the streets and the next thing, a policeman comes around and arrests or shoots somebody. You could just come and hang out here. It’s more of an escape from all the madness outside. The point is they are peaceful but they engage in a lot of anti-social habits, smoking, and drinking, but for me, they’re safe. We keep an eye on them but we want to see how we can engage them. How do we put them in touch with mentorship? Linking them with photographers or artists for mentorship. The next thing we need to do is to find the leaders in each group and see what we can do for them as a group. That’s the next step we are trying to get to now. You should come in on Sunday and see the crowd of young boys that come in here, no fighting, they just come here and hang out because there’s no space on the Island for them. “