The events leading to the Nigerian Civil War and the war, which lasted from 1967 to 1970, in spite of its tragic consequences were propitious for Nigerian literature in many ways. They altered the hitherto private sensibility of the Nigerian poet and pulled him into the national fray defined by political crises. The end of the war also became a convenient demarcating line signaling the emergence of a new generation of poets whose poetic afflatus was conditioned by the bloody feud. The next two decades after the war were to witness the beginning of the endless socio-economic and political contradictions that have almost wrecked the Nigerian nation. What follows in the poetry coming out of this experience is the motif of nationhood and its painful convolutions. If historians captured the essence of the Nigerian nation since the 1970s, the poets in their appropriation of the events provide an alternative historiography with vivid imagery and disturbing metaphors to the extent that it is safe to conclude than Nigerian history, be it social, economic and political, finds a flourishing habitat in Nigerian poetry. The two decades after the war were thronged with epochal events and were particularly excruciating, but exciting for Nigerian poets.

The painful aftermath of the war mixed with the euphoria of a new beginning morphed into a strong feeling which pointed in the direction boundless possibilities. There was the oil boom which not too long became a burst. There were military coups, political indirection and socio-economic fluctuations which buffeted the downtrodden. Misrule bestrode the landscape and corruption as well as economic mismanagement were menacing. The nation’s fluctuating fortune was grafted on two colluding factors namely; the benighted successive ruling class and exploitative foreign interests. In the hurly-burly of the throes of nationhood, the poets who emerged in the 1970s pitched tent with the struggling and suffering masses whose hopes and aspirations coalesced in the themes of the poetry they wrote. While the successive national governments remain the visible oppressors, the foreign interests such as the International Monetary Funds (IMF), the World Bank and oil-multinationals famed for inhuman capitalist greed were the behind the scene operators nudging the government as it balkanizes the nation and emasculates the working class. Thus in order to properly represent the suffering of the ordinary people and articulate their vision, some of the poets who emerged after the Nigerian Civil War embraced the praxis of Marxism as the ideological means of resolving the conundrum.

Tanure Ojaide, Pol Ndu, Ossie Enekwe, Dubem Okafor, Niyi Osundare, Odia Ofeimun, Obiora Udechukwu, were among the fresh poetic voices that articulated the Nigerian condition after the war. The Civil War and the hysteria it engendered reverberated in the poetry written by the aforementioned. Acute sense of loss resulting from death and waste occasioned by the war, chaos and other negative indices that dehumanized the people throb in their verses. Nevertheless, some of the poets did not sustain the promise exhibited in their first outing. But Ojaide, Osundare and Ofeimun continue to write and they have fostered that poetic tradition with many later and younger poets trailing them in versifying the Nigerian experience.

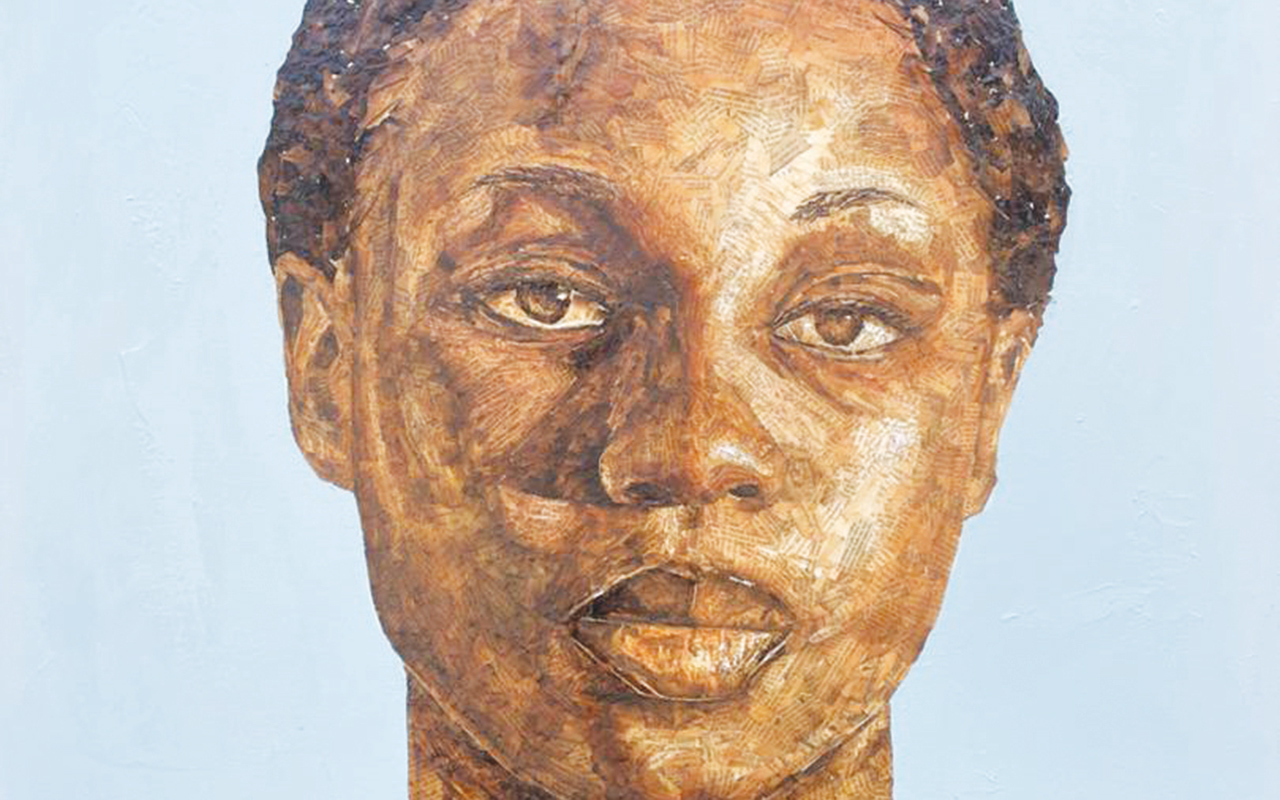

Moses Odafetanure Ojaide who turned seventy on 24th April 2018 has evolved to be one of the most outstanding poets not just in Nigeria and Africa, but the world today. A strong presence in the Ojaide-Osundare-Ofeimun poetic trio, Ojaide has aptly configured and reframed the Nigerian experience in poetry and prose, and provided critical insights into the appraisal of African literature and folklore. What marks out Ojaide in his literary vocation is his commitment to the representation of his homeland which primarily is Nigeria’s Niger Delta, the oil rich but devastatingly impoverished region that has suffered untold assault in both colonial and post-colonial periods. In collection of poems after collection as well as in prose, Ojaide depicts the region as a wasteland occasioned by the greed of the ruling elite and the rapacious oil multinationals. Often indulging in writing the self in his works, his poetry romantically evokes the idyllic ambience of his childhood in his Urhoboland homeland in the Niger Delta. His programmed poetic lenses take the reader beyond the contemporary into the past, receding into folkloric memory constituted by myths and legends which give the Urhobo their unique identity.

Ojaide’s poetic practice challenges hegemonic forces and offers an eloquent articulation of the plight and aspiration of the downtrodden even as it engages the history of Nigeria, Africa and to some extent the world. His writings, especially his poetry, demonstrate a keen awareness of contemporaneity. The zeitgeist of today’s world expressed through globalization and its manifold manifestations are given thematic emphasis in Ojaide’s poetry. A noticeable anger provoked by misrule, oppression and exploitation mark Ojaide’s poetry in the 1980s and 1990s which were predominantly the decades of military dictatorship. Together with his compatriot-poets, Osundare and Ofeimun, he wrote poetry which excoriated dictatorship, corruption and other vistas of misrule. While chastising the ruling class, Ojaide empathizes with the downtrodden of Nigeria.

His first literary offering is Children of Iroko and Other Poems (1973) can be read as giving a clear direction of what has become a flourishing literary career. Strongly rooted in Urhobo indigenous lore, the collection bemoans the consequences of the Civil War. However, it is for its privileging of Urhobo lore and life woven through indigenous aesthetics that the collection is best remembered. The poems bring into conspicuousness the religious rites, the pristine streams, the water goddess and other indices which define the existential experience of not only the Urhobo, but much of the Niger Delta.

The collection not only engages the new experience which the end of the Civil War offers, but the poems espouse a new aesthetic sensibility which inheres in the preoccupation with indigenous aesthetics that the poetry of the next generation of poets imbibed. The unflinching allegiance to the common man which was to dominate the poetry of the 1980s is also present in Children of Iroko. . . . Themes of deprivation, exploitation, corruption and military adventurism in the nation’s politics which define the collection turned out to be the thematic anchor of not just poetry, but also the drama and prose that followed. Hence, reading the collection without reading the poetry of Niyi Osundare, the plays of Femi Osofisan, the novels of Festus Iyayi and the works of other writers of the 1970s and 1980s would not represent a holistic engagement of the period in question.

Ojaide remains Africa’s most prolific poet and to his credit are twenty collections of poetry. After the first one already mentioned, Ojaide has published Labyrinths of the Delta (1986), The Eagles Vision (1987), The Endless Song (1989), The Fate of Vultures (1990), The Blood of Peace (1991), Daydream of Ants (1997), Cannons for the Brave (1997), Delta Blues and Home Songs (1998), Invoking the Warrior Spirit (1998), When it No Longer Matters Where You Live (1999), In the Kingdom of Songs (2002), I Want to Dance (2003), In the House of Words (2006), The Tale of the Harmattan (2007), Waiting for the Hatching of a Cockerel (2008), The Beauty I Have Seen (2010) and Love Gifts (2013) and Song of Myself (2015)..

His poetic oeuvre which has been translated into ten foreign languages can conveniently be divided into three phases which are however knit into one holistic engagement with Nigerian history and human experience. The first phase is occupied by Children of Iroko… which is his introit in the poetic vocation. It is a forerunner to the other collections which engage the unending problems of corruption, bad leadership, environmental degradation to other themes of universal import. So much has been said about Ojaide’s initial indebtedness to the poetry of Christopher Okigbo, but a familiar reader of his later works would trace the bold lyrical sweep and unpretentious commitment to an advocacy for the cause of the downtrodden, a strain which has remained consistent in his poetic practice.

The next phase comprises poems published from around the late 1980s to the 1990s. The period coincided with the advent of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP), the economic policy that was adopted by the nation in the late 1980s . The poems here constitute a significant diatribe against military dictatorship and its vagaries as well as economic exploitation and its attendant poverty. The poems also coalesce into a revolutionary framework against the background of the ecological crises in the Niger Delta which peaked with the hanging of Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Niger Delta environmental rights activist in 1995. The tone of the poems is unmistakably militant reflecting the prevalent mood of acute anger in the Niger Delta region. There is no doubt that the intensity of feeling, mood and language deployed by Ojaide helped in no small way in drawing the world’s attention to the grave ecological situation in the Niger Delta. In fact so intense and preoccupied are some of the poems in this phase that many critics tend to see him principally as a poet of the Niger Delta condition. But such a reading negates his pan-Nigerian poetic engagement.

The third phase of his poetry spans the years 2000 till date. The beginning of this phase of his writing is unique in that it was the beginning of a new century which also coincided with the end of military dictatorship. Since the main target, which is military rule, has been dislodged, the poet has to rethink new themes and directions. Ojaide did not have to look very far. The vestiges and memories of the preceding decade still provided matters and materials for his contemplation just as his eco-conscious preoccupation remains an abiding motif. Yet, an unmistakable new direction evolved in his poetry. Ojaide rethinks and privileges the many nuances of the rich oral poetic tradition of udje of the Urhobo people. Some of the titles of the collections carry such key words like “song”, “dance”, “words”. “tale”, etc to foreground the character of the indigenous heritage of poetry. A number of the poems here reflect Ojaide’s personality as a global citizen as they capture his travels and experiences thereof. While they can be described as travelogues they bear the mark of his Niger Delta homeland even as they reflect the scars which the Nigerian nation left on his psyche. The poems also lean towards metaphysical and abstract tendencies which very much differ from the earlier ones.

Ojaide’s literary career is also remarkable for his highly successful cross-generic experimentation. Although, he is better known as a poet, he was to venture into the genre of prose fiction weaving significant narratives that portray his comprehension of the anatomy and craft of fiction. To his credit are the following novels and short stories: The Old Man in a State House & Other Stories (2012). Stars of the Long Night (2012), Matters of the Moment (2009). The Debt-Collector & Other Stories (2009). The Activist (2006).Sovereign Body (2004), .God’s Medicine Men & Other Stories (2004).Ojaide’s fictional narratives resonate with the concerns of his poetic representations. His engagement with the prose genre has also seen him writing two memoirs in the realm of non-fiction namely: Drawing the Map of Heaven: An African Writer in America (2012) and Great Boys: An African Childhood (1998). His fiction, especially, The Activist, retells much of the poetic preoccupation with the Niger Delta homeland and the exigency of retrieving the region from the grip of its despoilers. The novel which is an archetype of homeland narratives projects a protagonist who embarks on a scheme of subversion in order to successfully rout the hegemony responsible for the predicament of the Niger Delta homeland.

Ojaide has also distinguished himself as a literary scholar and critic of the first rank. He epitomizes the Nigerian tradition of scholar-poets as his critical submissions in books and journals have become touchstones for literary scholarship in Africa and beyond. Among his full length critical studies on African literature and culture are Indigeneity, Globalization, and African Literature: Personally Speaking (2015).Contemporary African Literature: New Approaches (2012).Theorizing African Oral Poetic Performance and Aesthetics: Udje Dance Songs of the Urhobo People (2009).Ordering the African Imagination: Essays on Culture and Literature (2007).A Creative Writing Handbook for African Writers and Students (2005).Poetry, Performance, and Art: The Udje Dance Songs of the Urhobo People (2003).Poetic Imagination in Black Africa: Essays on African Poetry (1996). His robust critical output has enriched and updated literary scholarship on African aesthetics.

At seventy, Tanure Ojaide can look back and ruminate over his contributions to the global tradition of letters and the spheres of culture and society. The world has also been celebrating his phenomenal achievements. In recognition of which he has been well garlanded over the years. His creative and scholastic endeavours have earned him the following honours and awards: Commonwealth Poetry Prize (1987), BBC Arts and Africa Poetry Award (1988), All Africa Okigbo Prize for Poetry (1988 and 1997), Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) Prize for Poetry (1988, 1997, 2003 ad 2011), the 2005 UNC First Citizen Bank Scholar Award, the Fonlon Nichols Award (2014), the Nigeria National Order of Merit (2016), and many more. He has for more than a decade been the Frank Porter Graham Distinguished Professor of Africana Studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. His advocacy for the retrieval of his devastated homeland, the recovery of its purloined resources as well as restitution for its disillusioned people will continue earn him Uhangwha and Aridon’s cushioning. The drums have started rolling at Abraka! They will beat loudest on 9th May!

NOTE: “The Guardian Literary Series (GLS), which focuses on Nigerian Literature is published fortnightly. Essays of between 2500 and 5000 words should be sent to the series editor Sunny Awhefeada at [email protected].” 08052759540.

[ad unit=2]