“To my mind, promoting economic diversification is akin to weaving a beautiful traditional fabric. What do I mean by that? I mean weaving an economic fabric that is more complex, more resilient, and more beneficial to all families and communities. We know that economic diversification is good for growth. Diversification is also tremendously important for resilience.”

“To my mind, promoting economic diversification is akin to weaving a beautiful traditional fabric. What do I mean by that? I mean weaving an economic fabric that is more complex, more resilient, and more beneficial to all families and communities. We know that economic diversification is good for growth. Diversification is also tremendously important for resilience.”

This was how the then Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and current President of the European Central Bank (ECB), Christine Lagarde, summarised her perspective about economic diversification in 2017, three years before COVID-19 struck and exposed the underbelly of the volatile nature of resource-based economies, with particular reference to developing countries.

As the global community waded through the turbulence called the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the World Bank warned of dire consequences of the global shocks for the under-diversified economies but noted that the oil price crash offered a rare opportunity to such countries to expand their production and revenue base.

Of course, African countries readily come to mind when issues about diversification are raised. Thirteen out of 15 least countries on the economic complexity index (ECI) – as modelled by Cesar Hidalgo, a professor of applied science, and Ricardo Hausmann, a development economist – are from Africa. More interestingly, Nigeria (with -1.9 points) sits at the bottom of 133 countries in the ranking, which was last updated in 2018.

Interestingly, economic diversification, a phrase whose application is somewhat contentious, has been a policy option for successive administrations since independence. The policy became entrenched in the 1970s when the Dutch Disease took a hold of the economy and was on a steady course to strangulate the productive sectors.

For instance, the Olusegun Obasanjo military regime pursued a slew of policies to broaden the productive base and build a resilient economy. Diversification was also a strategic component of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) as initiated by General Ibrahim Babangida (rtd.). Since then, there have been dozens of reforms wholly or partly targeted at achieving a diversified economy though experts dismissed most of them as either ill-conceived or poorly executed.

Yet, some economists such as Dr. Biodun Adedipe of B.A. Associates Limited believes the economy is already diversified but that what remains largely mono is the external sector, which is driven largely by the exclusive crude.

Indeed, viewed from the perspective of gross domestic product (GDP) composition and a reflection on the character of the labour market, Nigeria does fit into the narrow definition of a mono-economy. In short, the contribution of oil, which is the mainstay of the country’s public revenue and foreign earnings, to the GDP since 2020 averages 7.5 per cent, ranging from a low of 5.2 per cent in Q4 ‘21 to a high of 9.5 per cent in Q1 ’20.

That implies that crude, which is considered by many as the lifeblood of the economy, does not control one-10th of the value of output. In the past two and half years, the non-oil share of the GDP was as high as 92.5 per cent.

In a less streamlined analysis, agriculture and industries, which are regarded as the engines of inclusive growth, have recorded average contributions of 25.3 per cent and 21 per cent respectively from 2020 to date. With telecommunications, banking and other service industries retaining the lion’s share (53.8 per cent) of the GDP in the same period, the economy could also be leaning, frightfully, towards services. That is another layer of the debate around diversification.

The Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) disclosed that the share of the country’s 69.54 million labour force engaged in the oil industry as at 2018 was 0.03 per cent. In the same year, oil’s contribution to output was 7.8 per cent. These data suggest that oil is a fringe sector in terms of growth and job creation when compared with agriculture, whose contribution to the labour market, hovered 35 per cent in the past few years.

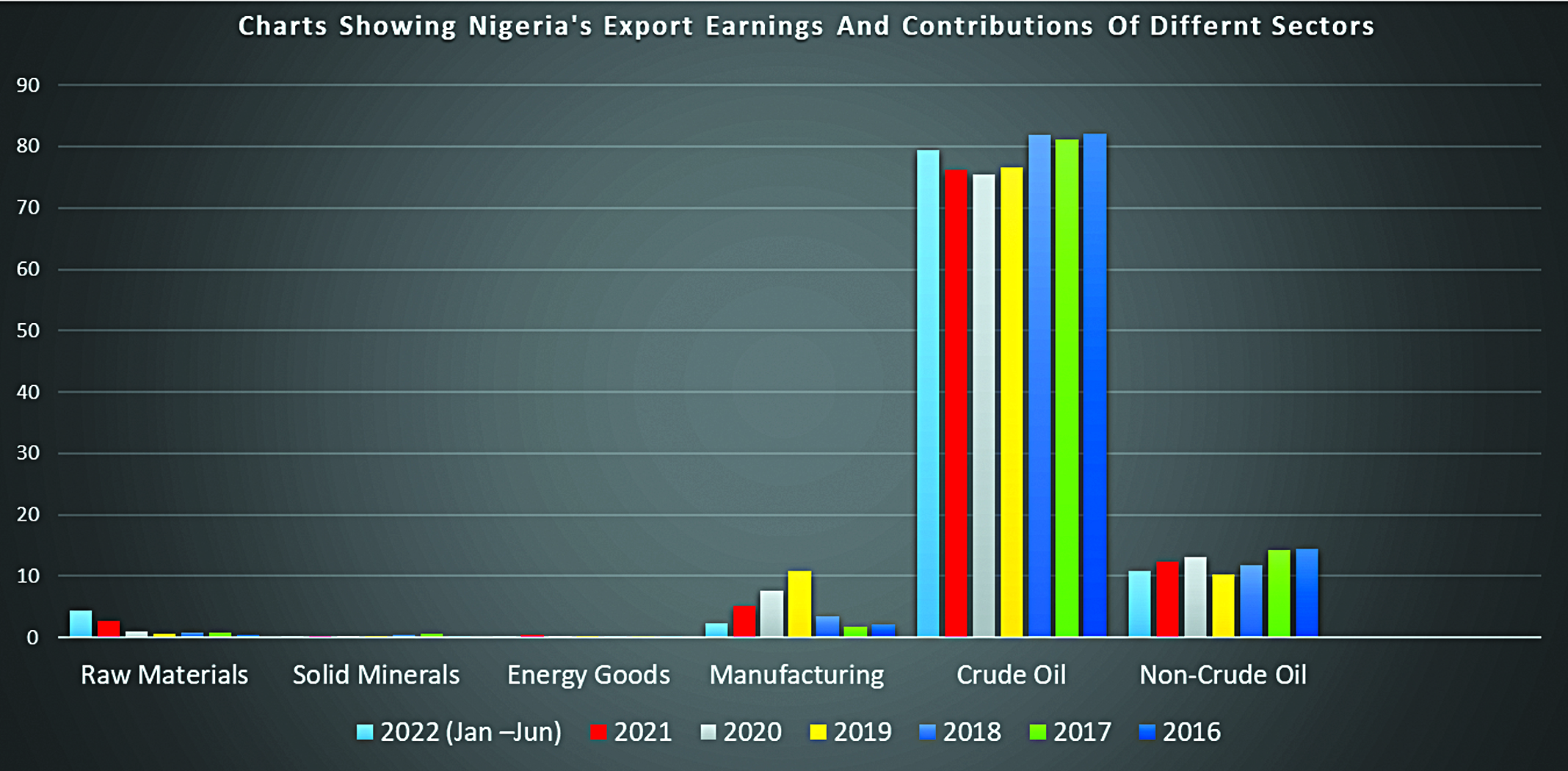

But these sectors reverse their roles in terms of public revenue and foreign exchange earnings. Of the total N7.4 trillion the country earned from export in Q2 ’22, as per data disclosed by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) last week, only N675 billion or 9.1 per cent came from non-oil while crude and non-crude oil controlled over 90 per cent. Mineral products generally constituted 91.5 per cent of the export basket. The contribution of minerals, whose prices are completely determined by exogenous factors, since 2018 has oscillated between 84.4 and 95.8 per cent. This has raised the level of fear that has called for the breaking of the concentration risk posed by the reliance on the petrodollar.

Non-mineral items are also majorly unprocessed and semi-processed. In Q2 ’22, for example, the top of the exported items were cashew nuts in shells, cocoa beans, sesame seeds, ginger and soya beans. Economic complexity is majorly assessed by the value a country adds to a product. In the same breath, economic complexity is measured by the knowledge quotient of the economic goods coming from the economy. In most cases, the net value of a country’s exported manufactured goods gives an idea about the nature of the country’s complexity – a reason Japan, Switzerland, South Korea, Germany, Austria, China, the United States and others rank very high in the ranking.

In Q2, the value of manufactured goods Nigeria exchanged with other countries was N2.88 trillion, while the export component stood at N119 billion. That puts the net import of manufactured goods over N2.7 trillion. On the other hand, Nigeria’s control of trade in manufactured goods was a scanty four per cent. Manufacturing, across regions and time, holds the ace to job creation – a reason the first port of call in efforts to expand the job market is stimulating manufacturing either through an increase in aggregate demand or using supply-side factors such as fiscal incentives.

Nigeria, like in previous quarters, spent a sizable portion of its foreign earnings on wheat in Q1. According to the foreign trade statistics, N 242.67 billion or four per cent of the entire import bill, was spent on wheat import, making it the third top imported item by naira value.

Like successive administrations, President Muhammadu Buhari had pledged to change this trajectory even before he assumed office under the tagline of making Nigeria a self-sufficient country in key consumable items. At the beginning of last year, Buhari told Nigeria that his plan to leverage the rich oil deposit to drive the country’s economic diversification, which kicked over seven years ago, was on track and yielding results.

In an interview with Bloomberg earlier in the year, Buhari said he has improved on the lots of Nigerians, insisting: “We have spent our two terms investing heavily in the national road, rail, and transport infrastructure set to unleash growth, connect communities, and lessen inequality. This is structural transformation. It may not show on standard economic metrics now, but the results will be apparent in good time.”

Perhaps, the new economy is rebooting slowly, as the President suggested. But data suggests fiscal diversification needed to prevent the country from skipping off the cliff is still an illusion, with less than nine months left in the life of the administration. The real sector, for instance, is increasingly less attractive to foreign investors.

From 2017, till the end of last year, Nigeria’s banking sector received a total of $15.83 billion or 23 per cent of the total capital imported into the country. In Q2 ’22, the share moved up to 42 per cent. The share of foreign funds that flowed into banking far exceeded that of production and agriculture combined. The two critical sectors shared 19 per cent. Foreign interest in agriculture and manufacturing has been dwindling.

The Buhari administration has less than a year to remarkably improve the contribution of non-oil to foreign exchange earnings and take it out of the five to 10 per cent range bound it has been in over a decade. And curiously, the country is not as ambitious as economists had wished in future-looking data they have shared.

For example, the 2023-2025 Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) is already seen as a rehash of the old culture that had been anchored on crude as the main source of income. If the premium motor spirit (PMS) subsidy programme does not end by mid-next year, the medium-term plan contemplates a zero budget for capital expenditure required for improved public infrastructure. That suggests that poor roads, insufficient rail networks and inefficient port facilities, which have partly constrained the growth of the real sector, will remain as they are in the meantime.

Interestingly, the 2023 budget is the last fiscal cycle the administration is left with to show how much the public finance framework has improved from the uninspiring position it was seven years ago when it took the reins.